Hong Kong has made big strides in organ transplantation over the years by allowing cross-family organ donations of kidneys and livers, but experts say many mental, legal and technical complexities have yet to be overcome. Li Bingcun reports from Hong Kong.

Surgeons of Princess Margaret Hospital (left) and Queen Mary Hospital (right) operate simultaneously in August 2021 during Hong Kong’s first cross-family kidney transplants. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Surgeons of Princess Margaret Hospital (left) and Queen Mary Hospital (right) operate simultaneously in August 2021 during Hong Kong’s first cross-family kidney transplants. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Till death do us part! It’s the vow many newly- weds take to cherish their love for each other for their whole lives.

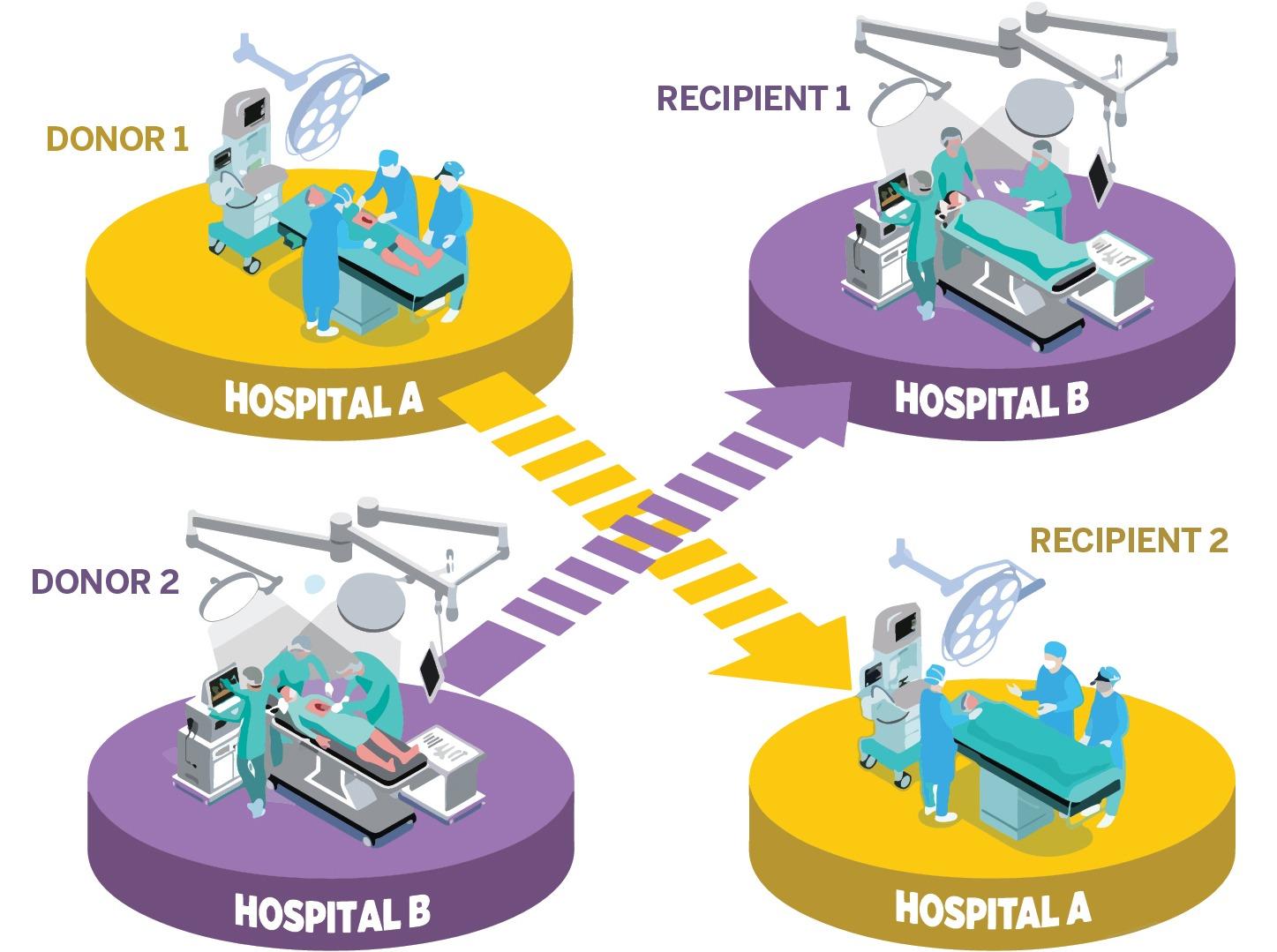

The pledge was symbolically carried out in Hong Kong when two married couples swapped kidneys, with one member of each couple receiving a kidney from a member of the other couple.

The kidneys were successfully harvested from the spouses in operations performed simultaneously at Queen Mary Hospital on Hong Kong Island and Princess Margaret Hospital in the New Territories in August 2021. The organs were then transplanted into the two patients, who had been on kidney dialysis for six years, after cross-match tests were conducted.

The patients, who were not named to protect their privacy, were discharged from the hospital about a month after the surgeries and were back at home in time for the Mid-Autumn Festival — one of the most important festivals on the Chinese calendar for families to come together and celebrate.

It was the first time that paired kidney transplants had been carried out in the city. Following a pilot program launched in 2018, if a patient’s family member is willing to donate a kidney to the patient but their conditions do not match, the family is allowed to make a cross-donation with another family in the same situation. Previously, organ donations from living donors could be made only by close blood relatives and spouses.

In addition to kidney transfers, Hong Kong has accomplished several cross-family liver transplants since 2009 with special approvals made by the Human Organ Transplant Board on a case-by-case basis. Facing a severe shortage of organ donations, Hong Kong is drawing on overseas experiences to widen the scope of donations from living donors by trying to overcome restrictions concerning blood type and marriage, seeking greater matching possibilities to achieve more life-saving miracles.

These attempts involve considerable efforts to update traditional mindsets, address the accompanying ethical and legal issues, and protect the safety and interests of donors and recipients to the fullest extent.

However, because of risks to donors, medical experts suggest that organ donations from living people should never be the first choice, and that the priority should be boosting people’s willingness to register as organ donors, allowing organs to be reused after registered people die.

Globally, such kidney exchange programs have been introduced in South Korea, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada, with surgeries performed two decades ago.

Besides paired donations, the US also allows “nondirected donations”, which means a donor can donate his or her kidney to any compatible patient. The largest kidney swaps were completed in 2014, involving 70 participants. Some global exchange programs have also carried out transnational kidney donations.

With Hong Kong’s relatively low organ-donation rate, more than 2,000 local residents are awaiting kidney transplants each year, with an average waiting time of about five years, and the longest 29 years. The number of kidney donations from living family members is less than 20 annually, while the number of cadaveric donations declined from 84 in 2012 to 45 in 2022.

Although renal-failure patients can receive dialysis to sustain their lives, organ transplantation is still the best option. Moreover, the quality of organs of living donors is considered better than that of cadaveric organs.

To offer patients another option, Hong Kong had been preparing to introduce the paired kidney donation (PKD) program since 2012, according to Chau Ka-foon, former co-chairperson of the Hospital Authority’s Paired Kidney Donation Working Group. After extensive discussions, the city revised the law in 2018 and officially launched the program.

Linda Cheng, who donated a kidney to her younger sister, Amy, 20 years ago, called the program a cheering breakthrough. Amy, the youngest daughter in the family, had been on dialysis for more than a decade since Form 5. She had to prepare for her college entrance examination while in the hospital.

As Amy’s condition worsened, she received a kidney from Linda in 2003. Amy’s three elder sisters were all willing to donate their kidneys, but Linda insisted it was her responsibility as the family’s eldest daughter.

“With the interchange program, not only can the lives of our loved ones be saved, we can also save those from another family. It’s a double impact,” Linda says.

An illustration demonstrates how cross-family surgeries are performed under Hong Kong’s Paired Kidney Donation program, launched in 2018.

An illustration demonstrates how cross-family surgeries are performed under Hong Kong’s Paired Kidney Donation program, launched in 2018.

Practical difficulties

Organ donations by family members are easier choices. But matters could get more complicated when a stranger is at the receiving end of the organ in the paired-donation mode. Doctors have designed various precautionary measures to protect both sides’ benefits and prevent coercion or commercial transactions.

The age difference between donors and recipients in paired donations is limited to 30 years, and both operations should be performed simultaneously. The identities of the two families are kept strictly confidential to avoid personal contacts. Participants also have the right to withdraw from the program at any time.

If a recipient fails to complete the transplant for various reasons after a donor has given out the kidney, the organ will be given to a suitable patient on the cadaver kidney waiting list to make the most of its value. For that recipient, if his or her family member had successfully donated a kidney, the patient would have the priority of securing a cadaver kidney.

Despite these measures, two families that were successfully matched in 2020 canceled their planned surgeries due to personal concerns. Chau explains that the families might have worried that the organ received was of lower quality than the one they donated. It would also be a heavy blow if a family donating a kidney were unable to receive one if an operation were to fail.

What they are concerned about goes further than that. Patients often struggle to decide whether to receive organs donated by family members, and some even strongly reject such donations, especially the elderly.

Although the surgical risks and aftereffects of living-kidney donations are minor, the donor may still have to suffer the pain and trauma, along with lifelong concerns about their own health condition.

More importantly, organ transplantation is not a once-and-for-all solution. The transplanted organ has a lifespan. A transplanted kidney usually lasts 15 to 20 years. If the new organ were to cease functioning after transplantation, the patient could only seek another donation or receive dialysis again.

With these concerns, some patients decline living organs and seek alternative ways. Martin Chan, a 40-year-old programmer, continues to receive dialysis twice a week, each taking about half a day, and is actively looking for a cadaveric kidney donation on the Chinese mainland.

“Anyway, it’s a fairly major operation. I don’t want donors to take the risks. Both my elder brother and sister have their own families to take care of. Due to their advanced age, my parents are also not suitable for donating a kidney to me,” Chan explains.

Attempts to swap organs among strangers have also encountered complex legal and technical problems.

In Hong Kong’s first-ever cross-family transplant in 2009, the medical team made a lot of efforts explaining to the Human Organ Transplant Board that the operation wasn’t a transaction. “We repeatedly emphasized that the two families did not intend to exchange organs. It was simply the medical workers’ proposal to raise the success rate of organ transplants,” says Lo Chung-mau, chief surgeon of the operation and also director of the liver transplantation center at Queen Mary Hospital at that time.

After all-night discussions of more than seven hours, the board approved the application and the surgery was successfully completed. But one of the donors developed a fever a few days later and was transferred to the intensive care unit.

It was a heavy blow to Lo, who is now Hong Kong’s secretary for health. He was worried it was due to complications arising from the surgery. A living-liver transplant carries greater risks than a kidney transplant — the mortality rate reaches 0.5 percent for right-lobe donors and 0.1 percent for left-lobe donors.

The team eventually found that the donor’s fever was caused by an allergy and wasn’t related to the operation. The donor subsequently recovered. “It always reminds me that a living-liver transplant is risky for the donor. No matter how careful we are, some problems that are beyond the domain of surgical technique may still occur,” Lo says.

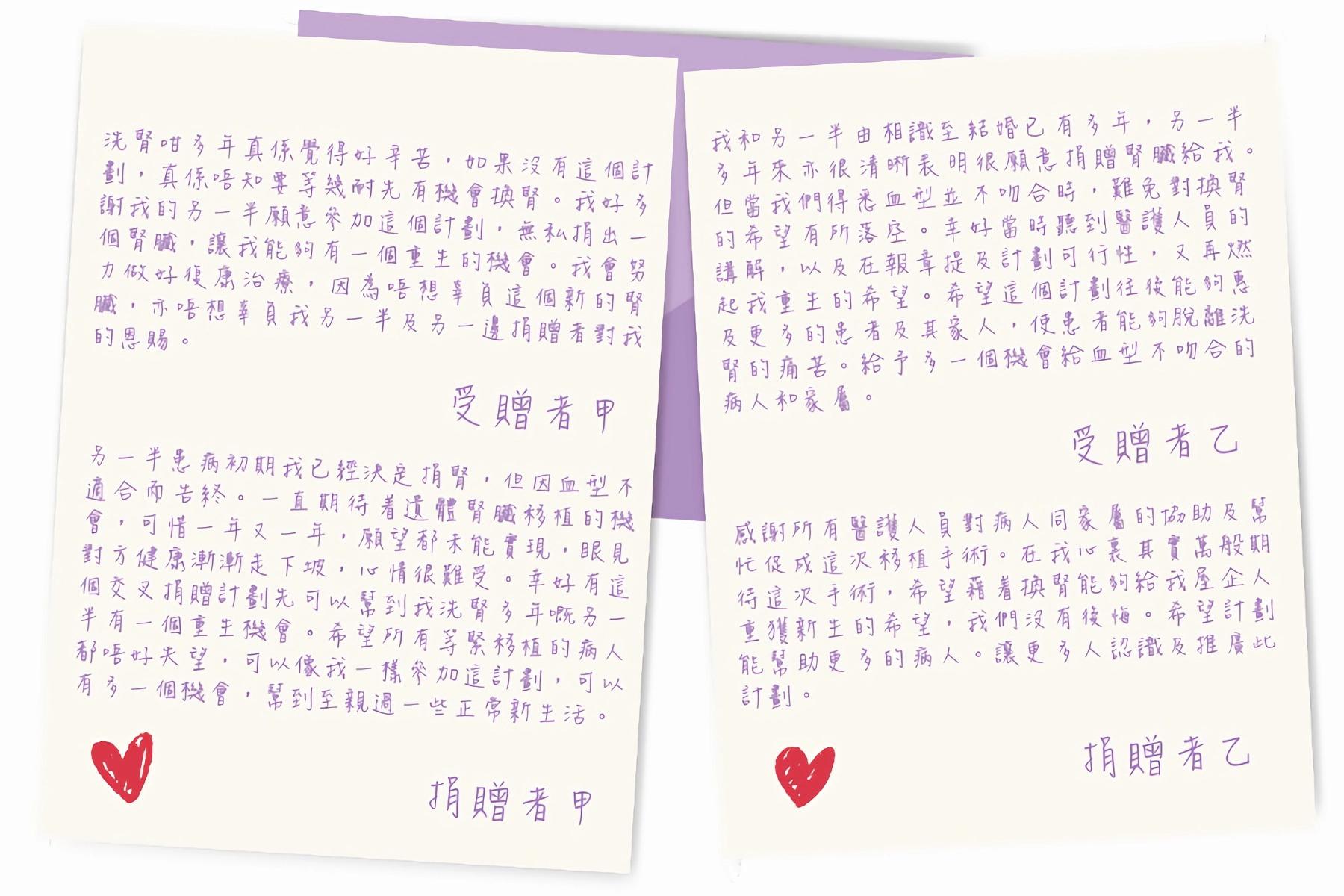

Thank-you letters from the paired families of kidney transplants. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Thank-you letters from the paired families of kidney transplants. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Future priority

The 2019 social unrest and the following COVID-19 pandemic presented even greater challenges for Hong Kong’s PKD program. In 2021, there were 26 eligible families in the city’s organ matching pool.

The Hospital Authority expects the number of participating families to climb to 50 to 100 in a few years. It will consider expanding the program to liver donations and collaborating with overseas matching pools. Chau hopes that kidney swaps will not be limited to just two families, and that multiple swaps among several families will be allowed to increase the chances of matching.

In addition to the pair-donation program, another heartening step has been taken in Hong Kong’s living-organ donation drive. Queen Mary Hospital has introduced new medical technology to address incompatibility between recipients and donors, according to Lui Sing-leung, a veteran Hong Kong kidney specialist. The technology allows patients to receive organs with different blood types by removing their antibodies with drugs and medical treatment.

But Lui warns that the city’s falling fertility rate has caused some side effects in living-organ donations. With fewer family members in the pool, finding a suitable living donor will be less likely. In the long term, the trend may further boost the demand for cadaveric organs and living donations from people who are not related by blood, he says.

Wang Haibo, a member of China’s National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee, says the pair-donation program is worth looking into and being discussed. The mainland is also conducting clinical research on paired-kidney donations. Alvin Roth, who won the 2012 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and developed a global kidney-exchange program, visited China before the COVID-19 pandemic to seek collaboration in this area, he recalls.

Wang says both Hong Kong’s and the mainland’s organ donation rates still lag far behind those of developed economies. “They have reached a plateau and have made relatively adequate utilization of organ donations from the deceased. We have much room to develop in this regard.”

He says that while officials explore innovative approaches concerning living-organ donations, the priority should still focus on how to boost people’s willingness to register as organ donors and better utilize the organs. “These are the so-called ‘low hanging fruit’. It would be wise to concentrate our limited resources on the most rewarded option.”

Worldwide, the number of living-organ transplants has gone up in the past decade. But with deceased-organ donation systems being practiced, their proportion in overall organ transplantations has been declining. Currently, living-organ donations account for about 10 percent of Hong Kong’s overall donations.

“After all, living-organ donations require a healthy person to undergo surgery for another person’s health. We will always consider organs from the deceased as the first choice,” Wang says.

Since the transplant, Amy Cheng now has three kidneys. The new one from her sister was placed on the left side, in front of her failed kidneys, and she can feel it when she touches her stomach.

Cheng recalls that if a cadaveric kidney were suitable for her 20 years ago, she would have chosen it even if the living-organ donation from her sister could have given her 10 more years to live.

“Instead of allowing organs to rot in the dirt or burn to ashes, isn’t it a better choice that they be reused to save others and their families?” she asks.

Contact the writer at bingcun@chinadailyhk.com