Exhibition sheds light on the importance of the written word in forging an identity, Wang Kaihao reports in Chengdu.

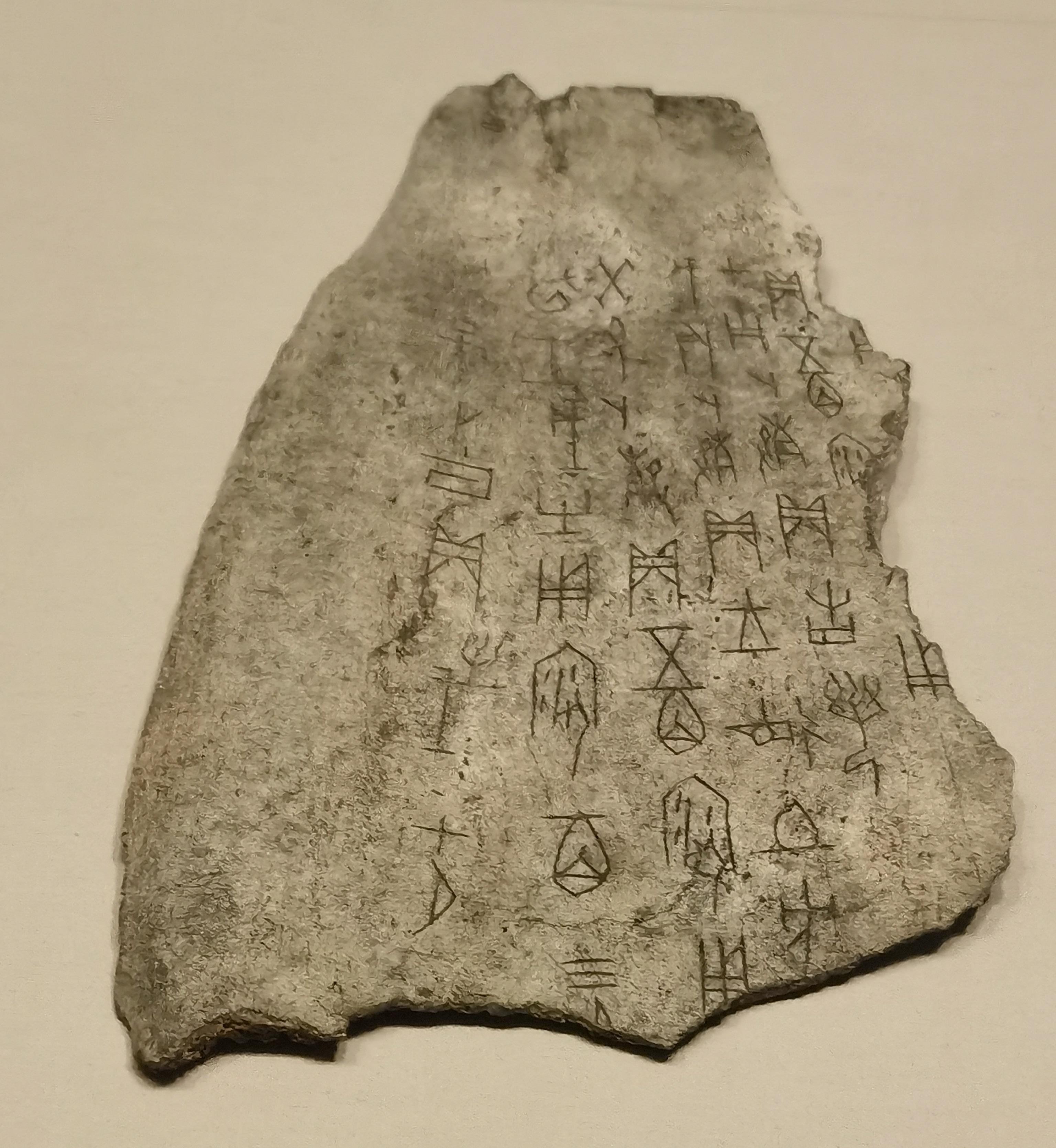

An oracle bone from the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC) is a highlight of China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

An oracle bone from the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC) is a highlight of China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Every time people write down a Chinese character, or hanzi, it may bear a cultural gene that has been inherited for millennia.

Throughout Chinese history, the country witnessed lasting unity ensuring prosperity, but it also endured dark years being torn apart by wars and social turmoil. However, thanks to the uniform and continuous writing system, a shared identity has survived and boomed.

China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing, a highlighted exhibition, raised its curtain earlier this month in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province, to unroll an epic, perhaps silent in its physical form but powerful in its nature.

About 220 cultural relics on loan from 40 institutions nationwide were brought together for the three-month display at the Chengdu Museum.

"Words condense the aspirations of generations," Wei Min, curator of the exhibition, says. "And classics preserve thoughts over time. The form and structure of hanzi and the instruments and media of writing have continuously changed.

"However, it has always embodied the philosophical thoughts, ethical values, and aesthetic tastes of the Chinese people, reflecting a nation's way of thinking and attitude toward life," she adds.

The well-known oracle bone inscriptions, carved on turtle shells and ox scapulae, among other things, are the earliest evidence of a fully developed writing system that has evolved into the Chinese characters used today. Dating back 3,300 years to the late period of the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th-11th century BC), most such bones were excavated from areas surrounding the Yinxu Ruins in present-day Anyang, Henan province.

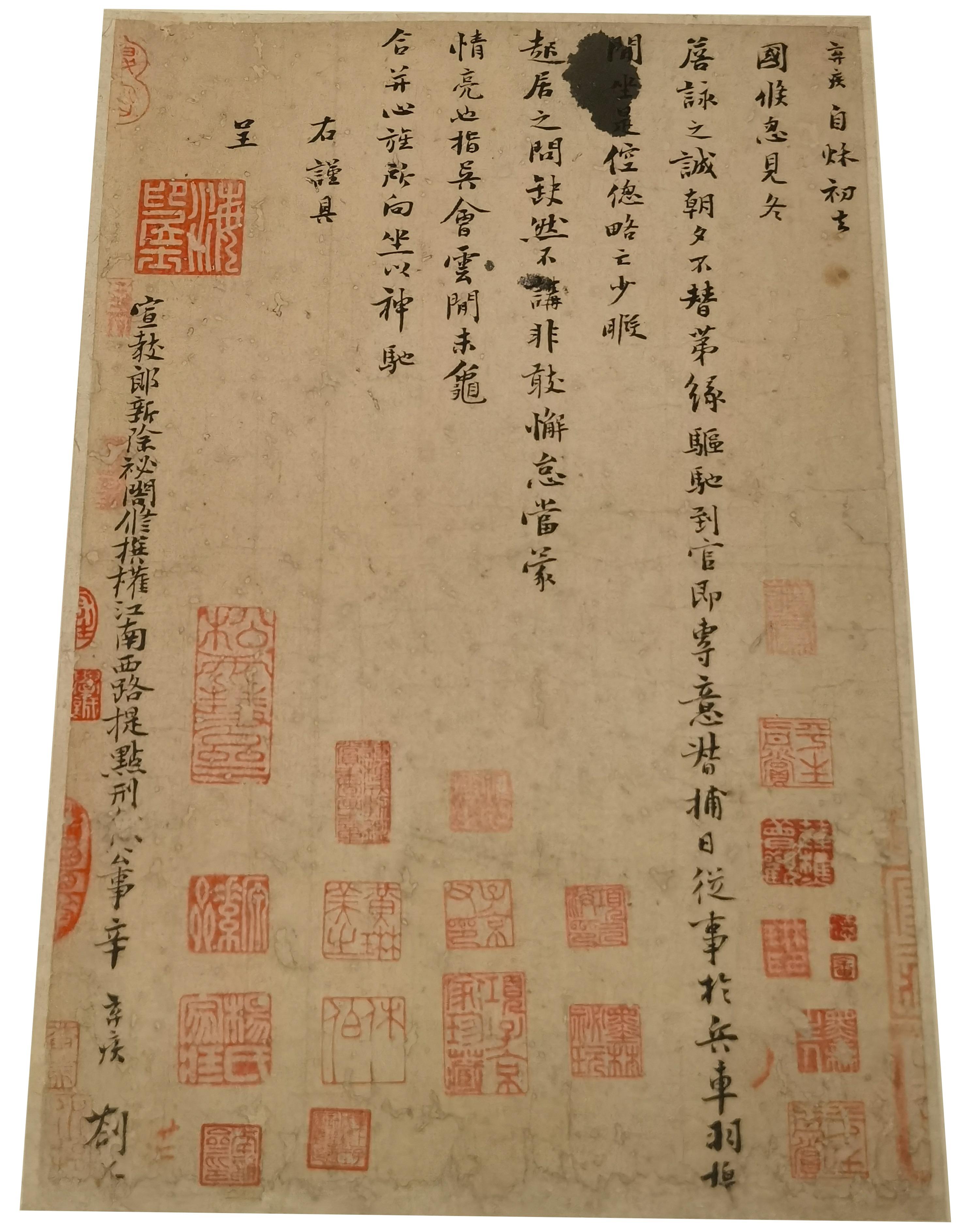

A 10th-century Confucian classic is a highlight of China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

A 10th-century Confucian classic is a highlight of China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

An oracle bone on display at the exhibition recorded a divination during Shang king Wuding's reign. The king foretold a heavy rain was coming, which he explained as an inauspicious omen. Thanks to what was written on the bone, this small moment of the distant past remains vivid. It also provides a key reference for modern people to understand the origins of Chinese civilization.

However, such a mature writing system apparently means there must have been earlier prototypes, as Wei points out. Carved marks may shed light upon people's imagination.

Many exhibits ushered visitors to trace those embryos of writing, including marks on a 7,300-year-old pottery from the Shuangdun site in Anhui province, on a black pottery jar of the Liangzhu Culture dating back 5,300 to 4,300 years in Zhejiang province, and on a tortoise shell of the Jiahu site in Henan province from 8,000 years ago.

The mark on the Jiahu tortoise shell resembles Chinese character mu (eye) in oracle bone inscriptions, according to Wei. It is so far the oldest artifact that indicates an origin of hanzi.

In spite of their age, oracle bone inscriptions fully reflect all character-formation varieties of later history.

"Through evolution from time to time, the appearance of Chinese characters has gradually become what we're familiar with today," Wei says. "The identity of a shared community of a Chinese nation has also been strengthened when the uniform writing system was gradually formed."

Before the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), bronze wares used to compose a main media for documentation. In the exhibition, Qiang Basin from the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century to 771 BC) with a 284-character inscription not only demonstrates high-level craftsmanship, but also remains crucial documentation.

A bronze tablet recording Qinshihuang's edict is a highlight of China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

A bronze tablet recording Qinshihuang's edict is a highlight of China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Unearthed in Baoji, Shaanxi province, the inscription eulogized the merits of seven Zhou kings, and it also briefly recorded stories of the family who made the basin. Highlights of history books surrounding the rulers and individuals who are absent in the grand narrative meet on this single artifact.

When Qinshihuang, China's first emperor, established the Qin Dynasty and united the country, he also promoted a uniform writing system absorbing characters from various regions. An exhibited bronze tablet carved with 40 characters, which was made in 221 BC when he united China, documented Qinshihuang's edict to standardize the nation's weights and measures.

"It vividly reflected how a nation's governing system was built up," Wei says. "It's a solid foundation of a united country with various ethnic groups."

Other than the political significance, hanzi epitomizes inheritance of culture and fine art.

Following the booming maritime trade of porcelain during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), Changsha Wares from present-day Hunan province traveled over the waves, also spreading people's artistic taste to distant shores. Artisans tended to write poems on the bottles and jars, demonstrating a golden age of literature in ancient China.

The 10th-century Confucian classics on stone from Chengdu are like an encyclopedia including all original texts of the classics, as well as explanatory notes.

In the era when China fell apart following the demise of the mighty Tang, the classics created in a small dynastic state centered on Chengdu, known as Later Shu, might reveal a common cultural root that explained why the country always reunited again.

Calligraphy, which displays the beauty of writing, has become an exceptional art form in Chinese culture. Literati, high officials, and even emperors' handwritten pieces turned a section of the gallery into a traditional Chinese study with refined cultivation. The exhibits are credited to a long list of top-tier Chinese calligraphers, including Zhao Mengfu, Mi Fu and Huang Tingjian.

The only surviving calligraphic work by famous Southern Song period (1127-1279) poet Xin Qiji is a highlight of China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

The only surviving calligraphic work by famous Southern Song period (1127-1279) poet Xin Qiji is a highlight of China in Light of Hanzi: The Splendor of Chinese Civilization in Writing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

As the whereabouts of the original piece of the 4th-century masterpiece Lanting Xu, or Preface to the Orchid Pavilion, remains unknown, Zhao's facsimile of what is one of the most important calligraphic works in Chinese history helps people to approach that lost cultural milestone.

Various scripts — regular (kaishu), cursive (caoshu), and semicursive (xingshu), not only reflect the writers' moods, but also show the general ethos and spirit of different times.

A poet from the Southern Song period (1127-1279), Xin Qiji, is a household name for Chinese people. However, only one of his calligraphy works has survived, and it is at the exhibition.

Due to his disagreement with the appeasement policy handling relations with the northern neighbor of Song, Xin, also an official and a general, was relegated down the ranks of officialdom several times. Nevertheless, he never swerved in his determination to recover lost territories for the country.

"Xin's characters are tall and straight, just like his strong personality," Wei says. "Putting this piece near the end of the visiting route, we want to remind people to think of the psychological strength hidden in Chinese characters. Viewing their writings, we can feel their morals and patriotism."

Nutrition provided by hanzi benefited a wide area beyond China. A section of the exhibition reviews its spread across Japan, Vietnam, and the Korean Peninsula through history.

"Absorbing Confucian ethics, these regions that were deeply influenced by Chinese culture also developed their own writing systems on the basis of hanzi," Wei says.

An exhibited book in hanzi, The Annals of the Great Koshi, first compiled by the 13th-century Vietnamese historian and then printed in Japan in 1885, is a perfect example showing such a cultural sphere.

"The beautiful words of hanzi and the human spirit they expressed are coordinates of civilization that have stood the test of time," Wei concludes.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn