A female physician in 15th-century China, Tan Yunxian, shattered a few glass ceilings to become a ‘doctor of repute’. Chinese American writer and fifth-generation immigrant Lisa See pays homage to her Guangdong roots in her fictionalized retelling of Tan’s story. Mariella Radaelli reports.

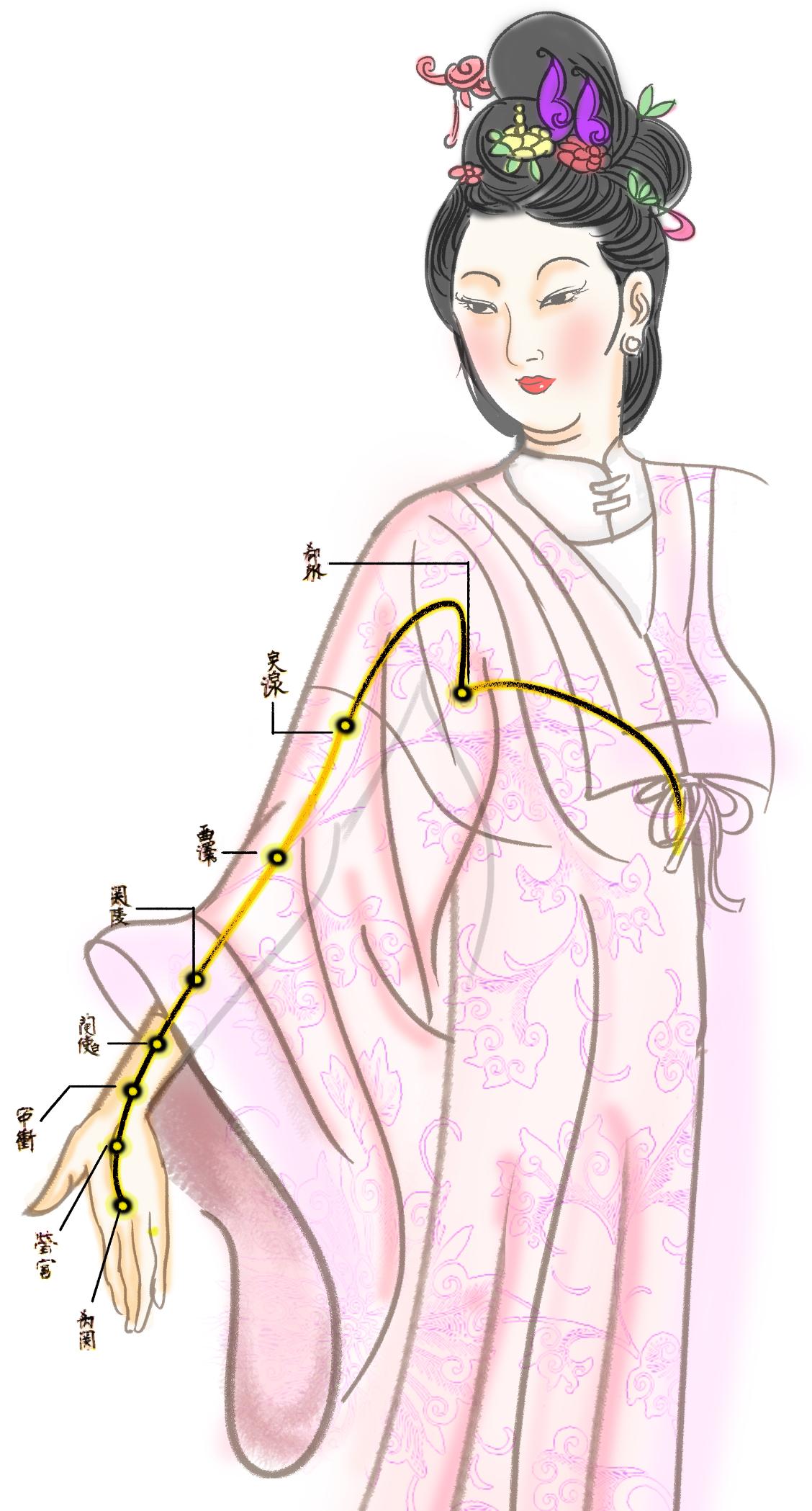

The main image shows the acupuncture points on the arm of the figure. Tan Yunxian used herbal remedies and acupuncture to treat her female patients.

(BILLY WONG / CHINA DAILY)

The main image shows the acupuncture points on the arm of the figure. Tan Yunxian used herbal remedies and acupuncture to treat her female patients.

(BILLY WONG / CHINA DAILY)

In 1469, the sixth year of the Chenghua Emperor’s reign, an 8-year-old girl from Wuxi had already found her mission in life — caring for women’s health.

Published in June, Chinese American author Lisa See’s novel, Lady Tan’s Circle of Women, is based on the story of Tan Yunxian (1461–1554), a trailblazer for women practitioners of Chinese medicine who had attained the status of a ming yi (doctor of repute). In 1511, Tan’s son Yang Lian published her book, Miscellaneous Records of a Female Doctor, containing the details of 31 medical cases. The publication was ahead of its time, paving the way for medical case histories to be counted as a genre. It anticipated the trend of publishing medical casebooks in China in the 16th century, which took off with Medical Cases of Stone Mountain (1531) by Wang Ji, a physician active in the culturally inclined, trading entrepot of Huizhou.

In 1585, Tan’s grandnephew, Tan Xiu, published a posthumous edition of her book. “The number of people she has saved is countless,” he wrote in the afterword.

Angela Leung Ki-che, professor emerita of history at the University of Hong Kong, says that Miscellaneous Records “reveals more about Tan’s empathy for her patients and therapeutic skills, rather than her interest in medical theories, an area dominated by elite male doctors”. “This unique work offers a rare view on illness and social life in Ming-dynasty (1368-1644) China, documented by an educated woman, which probably explains why it has seen at least two new editions in recent years (in 2007 and 2019),” she adds. There is also a noted English translation of the book by Lorraine Wilcox with Yue Lu, published in 2015.

Tan started practicing medicine at a time when, as per convention, male doctors examining female patients sat behind a curtain or screen, if not outside the room, in the hallway. “The woman’s father or husband would serve as the go-between, relaying the doctor’s questions to the patient and returning the answers to him,” See notes.

The emergence of female doctors like Tan changed the scene considerably. Tan kept her patients under close observation as she dealt with cases of pregnancy and childbirth, fertility and menstruation, gynecological disorders and other diseases. She was a skilled administerer of moxibustion — the craft of igniting mugwort sticks to warm the acupuncture points. A number of herbal remedies developed by her are still in use.

Lisa See’s novel, Lady Tan’s Circle of Women, includes a number of references to the culture of South China, where the writer’s ancestors are from. An elaborately carved bed that figures in the novel is modeled on a family heirloom inherited by the writer. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Lisa See’s novel, Lady Tan’s Circle of Women, includes a number of references to the culture of South China, where the writer’s ancestors are from. An elaborately carved bed that figures in the novel is modeled on a family heirloom inherited by the writer. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Reimagining history

Lady Tan’s Circle of Women takes the form of a bildungsroman told in the first person. Tan, the narrator, walks the reader through her formative stage, coming of age and eventually her mature years. After losing her mother while she was still a child, Tan is adopted by her maternal grandparents, who are doctors by profession. She is tutored by her grandmother, who comes from a family of Confucian doctors. Once her training is over, Tan turns into a busy, in-demand physician with a career lasting several decades. In between, she also finds time to get married, and raise four children, leading a rich and eventful life, until her death at the age of 93.

The medical cases described in the novel — as well as the people suffering from those illnesses — are genuine, taken from Tan’s Miscellaneous Records. However, See has used her imagination to flesh out the spare documented facts on Tan’s life. She has taken certain liberties with the available material, the most significant of these being the frequent allusions to South China. Though a fifth-generation immigrant, born and raised in the United States, See feels strongly attached to her South China roots. “My family is from Dimtao, a village in the outskirts of Guangzhou,” she says proudly. Her great- great-great-grandfather had moved to the US to work as a construction laborer on the transcontinental railroad in the 1860s. At one point, her great-grandfather, Fong See, controlled the Chinatown in Los Angeles.

The exquisitely carved bed Tan inherits from her mother in See’s novel is modeled on a real antique marriage bed from Guangdong, an heirloom that now sits happily in the writer’s California home. It comes with a carved, circular moon gate leading to a sleeping platform on which See would play in her childhood.

“My grandmother would put Chinese clothes and shoes in the bed’s drawers for me to dress up in. When they were small, my sons and their cousins played on the bed. Now we’re waiting for the grandchildren to be old enough to play on it,” See says fondly. “My ancestral bed seemed a perfect fit for my book. I didn’t have to find one in a painting or a museum because I knew this one so well, and it meant so much to me.”

The ancestors of California-based novelist Lisa See have a long history of traveling to and eventually settling in the United States. See’s great-great-great-grandfather went to America to work as a construction laborer in the 1860s. Her great-grandfather, Fong See (seen here with his American wife and children), went on to become an influential figure, practically running the Chinatown in Los Angeles. Though a fifth-generation immigrant, See feels spiritually connected to her ancestral land in Guangdong province. Her works are replete with ethnocultural references from South China. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The ancestors of California-based novelist Lisa See have a long history of traveling to and eventually settling in the United States. See’s great-great-great-grandfather went to America to work as a construction laborer in the 1860s. Her great-grandfather, Fong See (seen here with his American wife and children), went on to become an influential figure, practically running the Chinatown in Los Angeles. Though a fifth-generation immigrant, See feels spiritually connected to her ancestral land in Guangdong province. Her works are replete with ethnocultural references from South China. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Celebrating sisterhood

One of the most heartening features of the book is the depiction of strong ties between women. The theme of sorority appears like a leitmotif throughout Lady Tan. The protagonist is surrounded by a supportive band of soul sisters at every stage of her life. The strongest of these bonds is shared with her friend Meiling, who, following her family profession, becomes a midwife.

In 15th-century China, midwives were considered “polluted”. “Together with butchers and coroners, they were seen as belonging at the bottom rung of society’s ladder,” See remarks. Her novel, however, metes out poetic justice when childhood friends, Tan and Meiling, become professional partners, delivering a future Chinese emperor together, in the empress’ private chambers at the Forbidden City.

Tan never visited the Forbidden City in real life, but in See’s fictionalized re-telling of her story, she meets Empress Zhang, who is depicted as a patron of the arts. The empress commissions skilled artists from the south of China to embellish the palace walls. See includes a real painter, Li Zai (unknown-1431), known for adding fantasy elements to his ink landscapes, among the commissioned artists and imagines him as creating a striking array of Daoist images. On seeing Li’s works, Tan exclaims, “All that is unique or valuable comes from the south, and the people of this desolate outpost (Beijing) have made good use of our bounty.”

Book cover of Lady Tan’s Circle of Women. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Book cover of Lady Tan’s Circle of Women. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Girl power

A product of painstaking research, Lady Tan illuminates several aspects of Ming China, warts and all. As See puts it, “On the one hand, it would have been an extraordinary time to be alive. On the other, there were a lot of downsides. Smallpox swept through the country every three years. Transportation was difficult. For the most part, women led very hard, confined and limited lives. That is one of the reasons why Tan comes across as such an extraordinary figure to me. She was a traditional Confucian woman in an arranged marriage, a mother of four, managing her husband’s household, and yet broke free of the restraints on women.”

Having a successful career in a male-dominated bastion in 15th-century China could not have been a smooth ride for Tan. Leung, the Hong Kong University academic, remarks that “female medical practitioners, including healers, midwives, ritualists and drug sellers, were active in imperial China, but typically criticized by the male literati as unruly and dangerous agents penetrating the boundaries between the female and male social spaces. Tan, however, was an exception.”

See captures Tan’s struggle through her bravura storytelling. Her novel is an engaging tale about an exceptional woman from the 15th century who wanted to save lives and ended up breaking a number of glass ceilings in the process.