Miscarriages leave thousands of Hong Kong families grief-stricken each year. Their predicament calls for greater community support and understanding to help them heal their emotions and rebuild their lives, Wu Kunling reports from Hong Kong.

The pain and torment experienced by any couple losing an unborn child are excruciating — a heartbreaking ordeal that’s likely to leave an indelible mark on their lives.

Tang, 35, and his wife, surnamed Cheuk, 36, went through just that in October 2021 when they had to give up their 23-week-old fetus with chromosomal abnormalities. They were overwhelmed with grief after months of squabbles that nearly tore their marriage apart.

It hurts me terribly when others try to comfort me, saying ‘it’s alright, you are still young and you will have another baby’.

Cheuk, a 36-year-old woman who experienced the pain of miscarriage

After exhausting every available quarter for help and advice to no avail, Tang turned to Grace Port-Caritas Miscarriage Support Centre — a project funded by The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust to provide comprehensive care and support for individuals and couples who have experienced a miscarriage, as well as emotional healing services.

The agony and suffering that arise from a miscarriage, medically referred to as a spontaneous abortion, affect thousands of families in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region each year, and only greater care and support from the community can help them move on.

According to SAR government statistics, one in five pregnant women in the city has suffered a miscarriage, whether it’s a spontaneous abortion or because of medical considerations or accidents, resulting in an average of 8,000 parents annually having to endure the pain of losing a premature offspring.

Among the challenges couples face after an abortion is that stillborn fetuses under 24 weeks’ gestation are not granted death certificates and other relevant documents required for burial or cremation. For a long time, only a handful of parents in Hong Kong were able to retrieve the remains of fetuses and hold funerals. To store the remains, some families opted for pet cremation agencies, or kept them temporarily in refrigerators at home.

The government responded in 2019 by commissioning the city’s first facility for burying abortuses at Wo Hop Shek Cemetery in North District — the largest public cemetery in Hong Kong. A similar facility entered service at Cape Collinson Columbarium on Hong Kong Island’s Eastern District two years later. The two facilities provide about 700 final resting places, enabling parents to arrange for dignified burials for their aborted fetuses.

In September 2022, the Home of Forever Love — the first government-run cremation facility for aborted babies — was launched in Kwai Chung in the New Territories. These supportive policies allowed Tang and Cheuk to retrieve and bury their child, offering them much relief although the emotional stress continues to linger.

Overwhelmed mother

Pregnancy loss, for whatever reason, is taboo in Chinese culture. The nature of gestation has created pressure on mothers, and the social stigma inhibits their willingness to seek help.

Cheuk, who gradually resumed work after months of physical recovery, still found herself overwhelmed by an unwavering wave of sorrow. She feels nobody truly understands the bond between her and her lost child. She still cherishes those moments when she felt the baby’s gentle kicks in her belly despite the discomfort caused by its growth. The absence of empathetic comprehension among those close to her, including her husband, aggravated her anguish.

“It hurts me terribly when others try to comfort me, saying ‘it’s alright, you are still young and you will have another baby’,” says Cheuk, as tears welled up in her eyes. She said that few of them truly grasp that, for a mother, a miscarriage is indistinguishable from losing a child who would have grown up alongside them.

She tried hard but failed to divert herself from the shock and misery she had gone through. The prejudices against miscarriage in society exacerbated her loneliness.

Many people, including some fathers, see a miscarriage as inauspicious. They tend to avoid open discussions about it and may prohibit the mother from bidding a final farewell to the fetus, citing superstitions of bad luck. Some even blame the mother for the misfortune, casting aspersions on whether she had done anything inappropriate during her pregnancy.

Cheuk says mothers face immense pain and tend to blame themselves for a miscarriage, pointing out that most natural abortions occur because there’s no other choice. The husband suggested new trips or taking up new hobbies like he used to help Cheuk overcome her grief without realizing that his wife underwent drastic changes in her emotions. As Tang’s frustrations mounted, Cheuk began blaming herself for her husband’s low spirits, aggravating her emotional stress.

The couple tried hard to avoid discussing the trauma which, instead of putting their lives back on track, led to continued quarrels. “I can’t understand why a miscarriage could escalate from a health issue to a marriage problem,” laments Tang.

Limited resources

In an attempt to rekindle the family warmth they once had, the couple decided to seek help elsewhere, without realizing they’d embarked on yet another challenging path. “Since the miscarriage, we’ve been searching for organizations specializing in this area, but nobody reached out to us on their own volition,” recalls Cheuk, calling it one of her biggest disappointments.

Many parents don’t realize the need for psychological counseling after a pregnancy loss as severe emotional problems may not show up immediately, she says. Few professionals they came across during the miscarriage procedure or afterward told them they could seek emotional support. “Even a leaflet or verbal notification would have saved us from months of desperate searching,” says Cheuk. They had learned that some public hospitals offer emotional counseling services for parents like them. But she found herself ineligible for such support as her miscarriage was performed in a private hospital. She was instead referred to a public hospital’s general psychiatric department and had to wait over three months for her first consultation session.

Subsequent appointments at the hospital were about two months apart, with less than one hour allocated for each session, which allowed the mother to reveal her problems but left no room for feedback from doctors. Adding to her frustration was that throughout the 18 months of counseling, her doctors were changed four times without informing her in advance. According to Cheuk, one of the doctors told her after their first counseling that he would not continue with the therapy as he was acting only temporarily.

“Recounting the experience of miscarriage and my repeated attempts to build up trust with new doctors made me feel like having rekindled my wounds,” says Cheuk. Her psychological stress persisted despite several counseling sessions at the hospital, forcing the couple to turn to social organizations for solace. It was only during their visit to Grace Port-Caritas Miscarriage Support Centre that they found comfort. They were advised and consoled by experienced social workers on the path to healing their wounds.

Proactive support

Elaine Chan Wai-ling, project supervisor at Grace Port, which is run by one of Hong Kong’s largest charitable groups, Caritas - Hong Kong, says they prioritize reaching out to families in need of help, with more than 1,000 people having participated in counseling and various activities there last year.

The facility’s social media pages have published touching stories of families that have suffered from miscarriage problems, as well as practical knowledge about mental and physical recovery following an abortion. Relevant posts have garnered over 200,000 views.

Comparing the number of people who actually seek help offline with those who silently search for advice online, Chan says many parents are still passive about soliciting help and prefer to endure the pain alone. She recalls that a mother had hidden the pain of losing her child for 14 years before seeking assistance.

Chan says hospitals and supporting organizations should proactively reach out to parents and guide them in aspects like burial arrangements for lost fetuses and enlighten them about what organizations are offering emotional aid.

Hospitals should also correct their approach to the problem of stillborn babies. “Some hospitals have refrigerated beds to allow parents to say farewell to their fetuses, ensuring utmost care in handling the remains. But, some parents are only allowed to do so in a hurry at the morgue,” she says.

Chan says medical professionals should be aware of the psychological, familial and interpersonal challenges faced by parents who’ve suffered pregnancy loss, and Grace Port has been training its staff in offering guidelines to medics and telling them how to interact with families in need.

Grace Port, which has an office in Tsuen Wan in the New Territories, has also been organizing events to disseminate related information and knowledge to affected parents. Chan hopes that the taboo of miscarriage can be eliminated in society, and people shouldn’t feel ashamed about discussing it, thus offering parents greater support and comfort.

Social worker Arnold Leung Tsz-tun set up an organization four years ago, dedicated to providing emotional succor for parents who’ve suffered from miscarriage — the first of its kind in the SAR. Having witnessed the growing awareness of the problem and backing for such parents over the years, he notes that inadequate resources and funding, coupled with weak public education on abortions, have failed to instill in the public a more positive attitude toward miscarriage.

Leung met parents who had endured such anguish for the first time in 2017. Despite having more than a decade’s experience in grief counseling, he was shocked by a plea for help from a mother who had lost her fetus and had not realized that a vacuum remained in assistance for this vast, yet invisible group.

Within two years, Leung had given face-to-face advice on how to overcome emotions to some 40 couples, and has appeared frequently as a guest on radio programs. He has also published a book and co-authored others with some parents he had helped, trying to draw greater attention to the issue.

Long way to go

Four years on, Leung is happy seeing more organizations emerging in Hong Kong to lend a hand to couples affected by the trauma. However, raising funds remains the biggest obstacle, forcing his organization to put up the shutters for the time being.

Adding insult to injury, Leung says some experienced medical professionals lack respect for a fetus, viewing it as an “object”. He quoted a mother as having been told: “If you don’t want it, I can help you dispose of it.” Hong Kong, he says, has a long way to go in promoting people’s regard for stillborn children.

ALSO READ: A garden for angels

Cheuk’s mental health has stabilized, and she has shared her road to recovery on social media and received an overwhelming response from mothers who’ve suffered the same misfortune. They empathized with her feelings, showed encouragement, and thanked her for speaking up on their behalf. Cheuk was astonished by the sheer number of people who’ve suffered like herself, calling for more public resources to help those in need.

Having been involved in family services for more than 30 years, Chan says support from the community will have a profound effect on the well-being of families that are the cornerstone of society. She notes that many family conflicts, such as those related to marital relationships, sexual intimacy, connection with relatives-in-law, and educational concerns, originate from the unhealed pain of miscarriages.

As Hong Kong strives to lift its dismal childbirth rate, stakeholders should consider allocating more resources to restore couples’ courage in starting a new life. Such support will form a key piece of the puzzle.

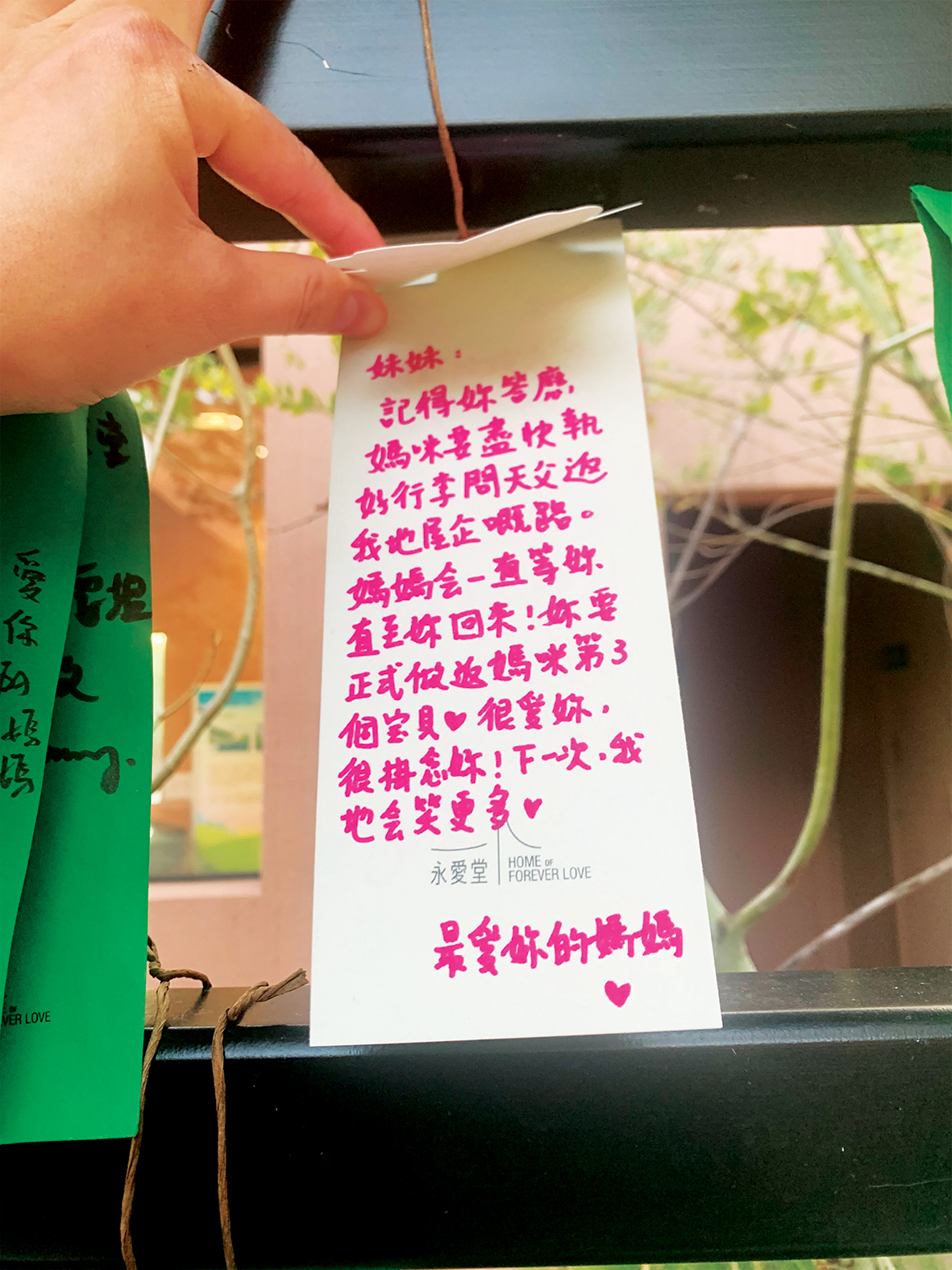

Outside the pink building of the Home of Forever Love in Kwai Chung, where many miscarried fetuses are cremated and laid to rest, parents have left commemorative cards expressing love for their lost children. Many heartbroken parents tell their little loved ones that they will meet again in the future, inviting the angels to join the families at an appropriate time.

After enduring a second heartbreaking miscarriage, Tang and Cheuk, with the support of professional social workers, have regained the courage to rebuild their lives. In a few months, the sound of their newborn child’s cry will bring a hard-earned sense of joy and mark a new beginning for the family.

Contact the writer at amberwu@chinadailyhk.com