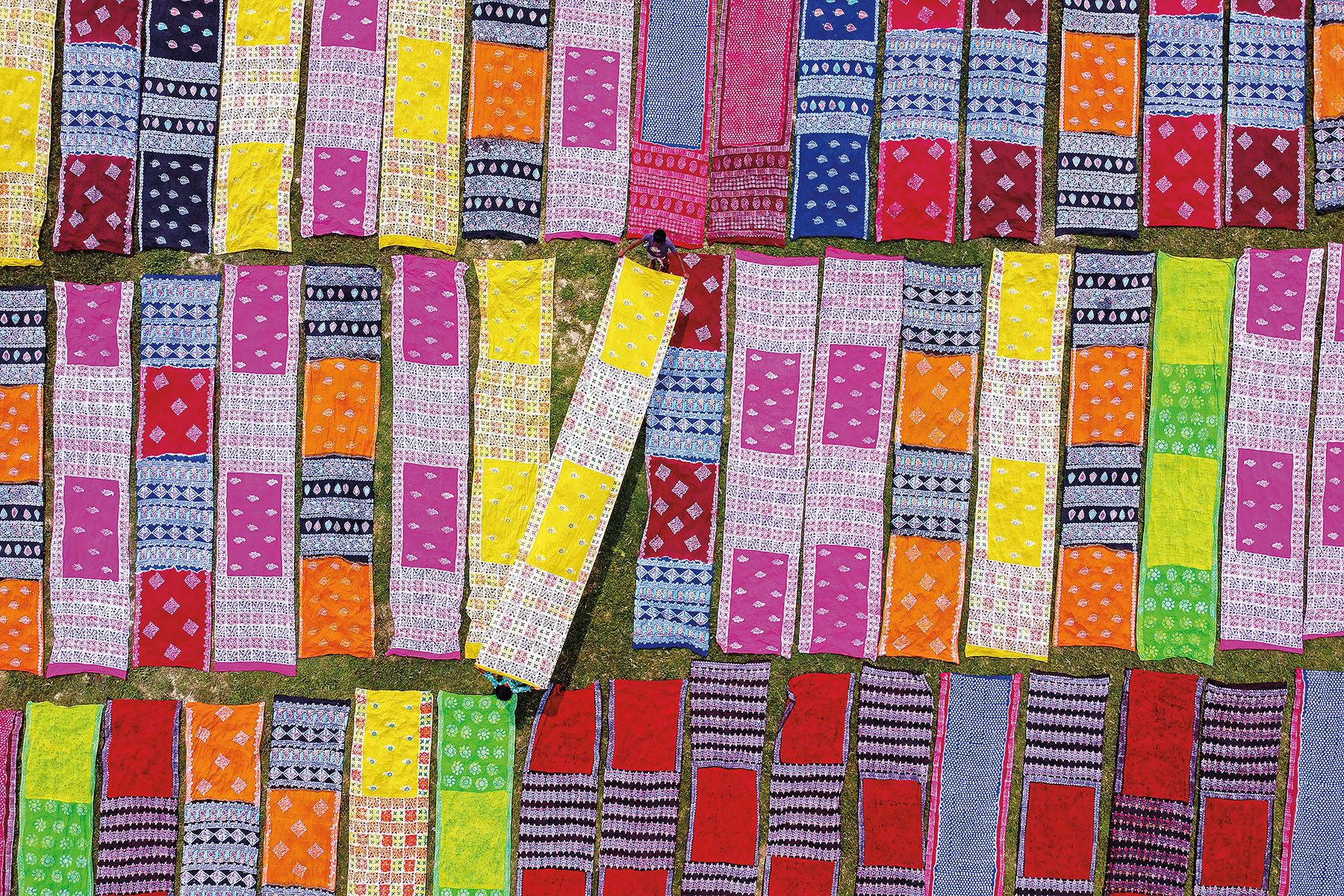

Bangladeshi artisans of traditional sari clothing struggle amid economic woes

Editor's note: In this weekly feature China Daily gives voice to Asia and its people. The stories presented come mainly from the Asia News Network (ANN), of which China Daily is among its 20 leading titles.

The industry behind traditional southern Asian attire like the sari and panjabi, worn in areas such as Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Pakistan, is increasingly facing the challenge of economic change and development.

Bangladesh's traditional textile sector has deep roots, extending back centuries and interwoven with the nation's cultural identity. The taant sari, traditional female Bengali clothing, can be traced to the eastern Bengal region.

The sari, woven from cotton threads and distinguished by its lightness and transparency, is considered to be extremely suited to the hot and humid climate of the Indian subcontinent.

READ MORE: Under the strain

Bangladesh's taant industry is a vital piece of its cultural and economic fabric. The traditional art of weaving is considered the best sari of its kind, listed by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

The sector's resilience has withstood economic downturns and other challenges but it is now facing a major threat — consumer disinterest, limited local support and imported alternatives.

Kutub Uddin, from the Benaroshi Polli, Mirpur 10 area of Bangladeshi capital Dhaka, has been weaving since childhood. He reflected on how his career began out of necessity amid Bangladesh's development, with his poverty-hit family relying on weaving to survive.

Over the decades, he watched as demand for handloom Benaroshi sari products fluctuated, with recent years seeing a noticeable decline.

"Ten or 12 years ago, Benaroshi sari was in high demand," he said. "But now, the industry is in crisis."

Although demand rises slightly during the wedding season, imported sari products, especially from India, flood the market and divert customers away from local artisans, he said.

The weaver said that creating a Benaroshi sari can take anywhere from a few weeks to several months, depending on its intricacy. In the past, he worked alongside a team where each person specialized in a step of the process, such as twisting threads.

But many of his former colleagues have left the industry, taking up jobs as rickshaw pullers or in restaurants to support their families.

Today, local weavers like him said they are overshadowed by cheaper, imported alternatives, which deprive Bangladesh's taant industry of the support it needs to survive.

The process of creating a handloom sari is labor intensive and requires immense skill, yet the artisans are paid modestly for their work. One weaver said that they can be paid per yard, with a single weaver managing to produce three to four yards on a good day.

Each piece they create is a labor of love, meticulously crafted to perfection. But it is also a product of rising material costs. The price of thread, dye and silk has increased significantly over the years, squeezing profit margins and leaving weavers struggling to sustain their craft.

The weaver pointed out that while one might expect the wedding season to boost demand, reality paints a different picture. Customers often overlook locally made handloom sari in favor of imported options, limiting local weavers' access to new business.

Tough times

For many artisans, the art of weaving is a family tradition, with skills passed down from generation to generation. But the economic realities of weaving have made it harder for artisans to encourage their children to continue in their footsteps.

Sari seller Sandip Basak described how increasing production costs and low sales affected his business during recent festive seasons when demand was expected to rise.

Sales were disappointing and many artisans now face the prospect of leaving the handloom industry altogether.

"If this trend continues, we might not have anyone left to pass on this knowledge," he said.

The loss of generational knowledge is one of the most significant threats facing the handloom industry. If young people do not see a viable future in weaving, they may pursue other professions and that will lead to the disappearance of traditional techniques that have been refined over centuries, many in the industry said.

ALSO READ: Plugging gaps: Foreigners seeking permits to work in Bangladesh

A weaver named Md Sajib who once served a steady base of clients has found himself in a difficult position, with his most loyal clients beginning to cancel orders due to rising prices. He has reached out to banks to secure a loan to sustain his business, only to be denied.

Banks do not want to lend their support because they believe the market is struggling, he said. For him, the future of the taant industry relies on customers and financial backing.

Weavers' calls for financial assistance are considered to be more than pleas for personal relief — they reflect the need to protect an industry deeply connected to Bangladesh's identity. Industry observers said that without support, the weavers risk losing their income and a part of their heritage.

One weaver said the country's sari is unique and people should understand that, "so weavers like me can continue our work".