Exhibition sheds light on late artist paying tribute to the man who guided him on the odyssey, Lin Qi reports.

In an article written to commemorate the death of Lin Fengmian (1900-91), painter Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010) recounted the events of a trip to Hong Kong in 1989, when he attempted to call the former teacher.

Lin had been Wu's headmaster at the Hangzhou National College of Art, today's China Academy of Art, in Zhejiang province.

Lin didn't answer, so Wu left a message with the number of where he was staying, and then waited and waited for the rest of the day.

"At midnight, the telephone rang. I asked who it was. At the other end of the line was a voice, saying, 'Fengming'. I didn't recognize the name until the man continued. 'This is Lin Fengmian.' I was surprised and delighted.

"My former teacher said he had spent the day in the suburbs. Fearing that I would leave the following day, he called as soon as he returned home and heard my message. My tears wet the telephone."

It was Lin's use of his given name in the phone call, an indication in Chinese culture of the closeness that he felt for Wu, that had touched the latter's heart so deeply, moving him to tears. Also, they hadn't seen for years, and each experienced turbulences in life.

Wu sorrowfully recounted this meeting with Lin in an article written on Aug 13, 1991, a day after his former teacher died, at 91, in Hong Kong.

At the end of it, Wu wrote, "I was sleepless last night (after hearing about Lin's death). As I'm writing now, it is early in the morning. I'm in the woods and sitting on a stone. Birds are singing on the trees. May all the birds make their singing be heard by the world!"

The last sentence included a homophonic play on Lin's birth name, fengming, which means "the chirping of a phoenix".

The original manuscript of this touching tribute is currently on display at The Road to China Modern Art, an exhibition of paintings, photos and documents running until Jan 3 at the Tsinghua University Art Museum. It juxtaposes the lives and careers of Lin and Wu, who are recognized as courageous, experimental and dedicated leading figures in modern Chinese art, and celebrates a lifelong attachment despite the distance between them, Lin having moved to Hong Kong in 1977 and Wu living in Beijing.

Their bond was born in 1936 when Wu enrolled at the school where Lin was teaching.

Wu, born in Yixing, Jiangsu province, studied electrical engineering for a year at a school that has now become part of Zhejiang University before meeting Chu Teh-chun, one of Lin's students, during a campus activity in one summer vacation. A visit to Chu's college changed Wu's life. He discovered a passion for fine arts, quit engineering against his family's will, and re-enrolled as an art student at the college where Lin was teaching.

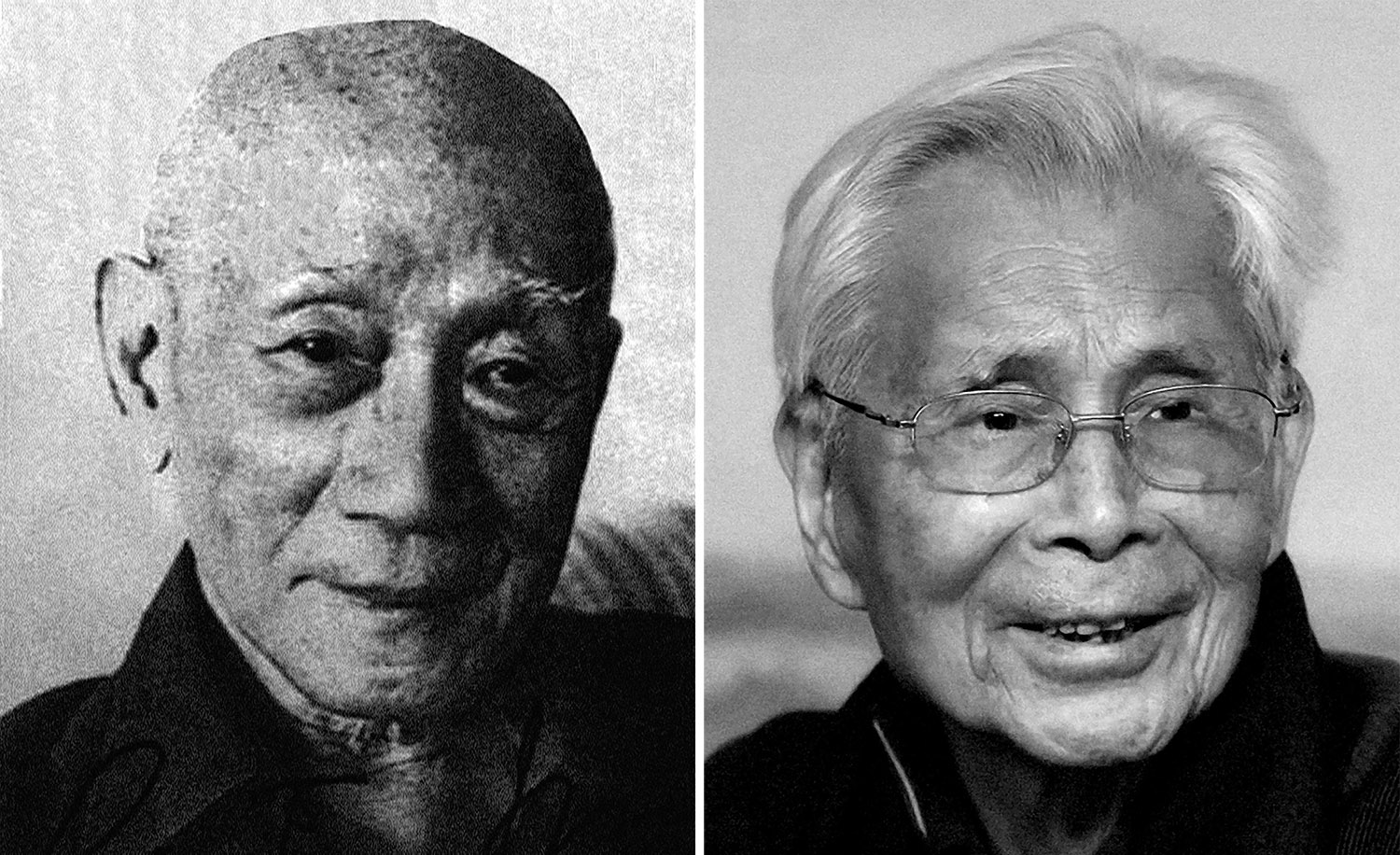

Lin was in the midst of forging a new path for Chinese art in the face of opposition from conservatives. In 1919, he had gone to France on a work-study program and attended several art schools, including the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He returned in 1925, first to head the National School of Fine Arts, today's Central Academy of Fine Arts, in Beijing, and three years later, to oversee the establishment of the Hangzhou National College of Art, becoming its first principal.

READ MORE: Shanghai exhibition paints picture of change

While in France, Lin was introduced to modern art. Upon his return, he dived into an ambitious venture to integrate Western art, a vanguard, free spirit, and Chinese culture, as a way of reforming Chinese art.

Lin shared his endeavors with his students in the hopes they would create pieces that addressed emerging social issues, and use art to nurture hearts and minds.

Wu was one of those motivated to follow suit, and in the decades that followed, he dedicated himself to the task. In 1947, he was granted a government scholarship to continue his studies at Lin's alma mater in Paris.

Today, Wu is referred to as one of Lin's three most influential students, alongside Chu and Zao Wouki. The three have gained recognition in China and internationally and were all members of the French Academy of Fine Arts (Academie des Beaux-Arts).

Standing at the crossroads of the East and the West, they each blazed trails that took modern Chinese art to new realms.

Xu Hong, a co-curator of the exhibition, says whether it is Chinese ink paintings or oils, Lin's work reveals the solid training he received in France, while demonstrating the "serene mood and deep spiritual resonance that are essential to Eastern art".

The soft luster and smooth silhouettes of Chinese porcelain, the diverse folk culture and court paintings of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) greatly interested Lin and were the three main sources of inspiration that defined his work.

"He tried to re-create the gentle glaze of ceramics with his strokes. His depictions of young women from ancient times embody the same elegant curves of a porcelain vase, and he would sometimes draw such a vase beside the female figure in the painting," Xu says. "He was able to present a classical beauty that is grounded on his understanding of Chinese and European cultures."

She says the recurring motifs in Lin's paintings, like woodlands, lush trees, Chinese opera performers, beautiful historical women and vases of flowers, display a vigor within backdrops that convey expansiveness and quiet. "It is a beauty that transcends time and space, the beauty of modern art."

Lin was a master of color. "He once joked that he was a 'slave' of color. He had experienced too much. The ups and downs of life, and the sadness and happiness had turned into these colors of brightness and darkness in his paintings", Wu once remarked of his teacher's work.

Wu himself was pursuing what he saw as the ultimate beauty of form, and the varied combinations of geometric structures, lines and dots define work in which he melded Western abstraction with Chinese minimalism and symbolism.

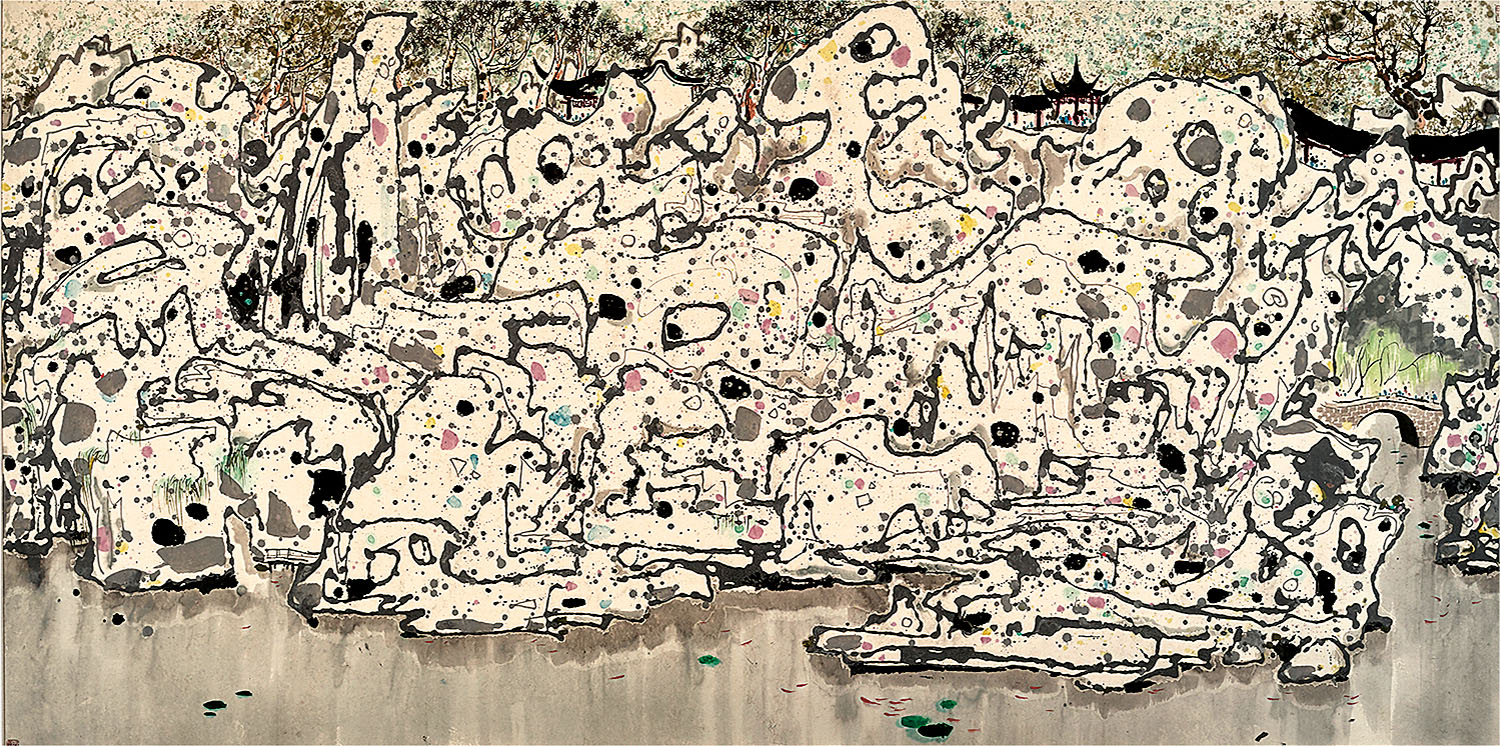

One famous example on show is the Shizilin, or Lion Grove Garden, a colored ink painting done in 1983, that is nearly 3 meters in length.

Currently part of the collection of Shanghai's China Art Museum, the painting depicts jiashan, or a faux mountain, an important part of classical Chinese gardens that are piled with hollow rocks of varying sizes, shapes and textures. The "mountain" occupies over four-fifths of the whole composition. In a departure from the traditional way of depicting gardens, Wu used ink lines and colored dots to represent the rocks and the rock mountain, and it is this bold, new style that distinguishes the painting as a brilliant example of the depiction of the classical private gardens of Suzhou, Jiangsu province.

Wu followed in Lin's footsteps becoming an educator. He taught first at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and then at the Central Academy of Arts and Design, today's Academy of Arts and Design, at Tsinghua University, before retiring in 1985.

ALSO READ: Art show displays creative exchange

"What he taught was not knowledge, but how to imagine, create and express beauty in boundless forms," says Liu Jude, head of the Wu Guanzhong Art Research Center at Tsinghua University.

Xu says Lin and Wu's work is a glimpse of the expansive nature of modern Chinese art. "As it absorbed elements of Western art, it didn't forget its own cultural traditions … which inspired artists to explore and create, and became a foundation on which new forms of art thrived," she says.

Wu once said: "Tradition is …like a big river.

"It flows upstream against currents, experiencing collisions along the way, constantly transforming itself in the process."

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn