In the third and final installment of her series on how museums in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area are interpreting the Silk Road for a contemporary audience, Chitralekha Basu finds out about the use of new-media tools and new artworks paying homage to the Silk Road spirit.

Almost every museum exhibition has an immersive component to it these days. It’s de rigueur to use virtual reality, augmented reality and other new-media technologies to create environments that aid and abet a visitor’s understanding of an exhibition’s content.

Since the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area is a fertile ground for “art tech” experiments, and since seasoned museum visitors have been treated to “immersive” new-media experiences for over a decade, exhibition designers today are expected to use advanced technology in ways that go beyond creating spectacles.

ALSO READ: Tale of three cities

Reassuringly, some of the Greater Bay Area museums hosting Silk Road-themed shows this year harness new media to not only confer an extra layer of meaning on the physical exhibits but also to expand the scope of the traditional exhibition model.

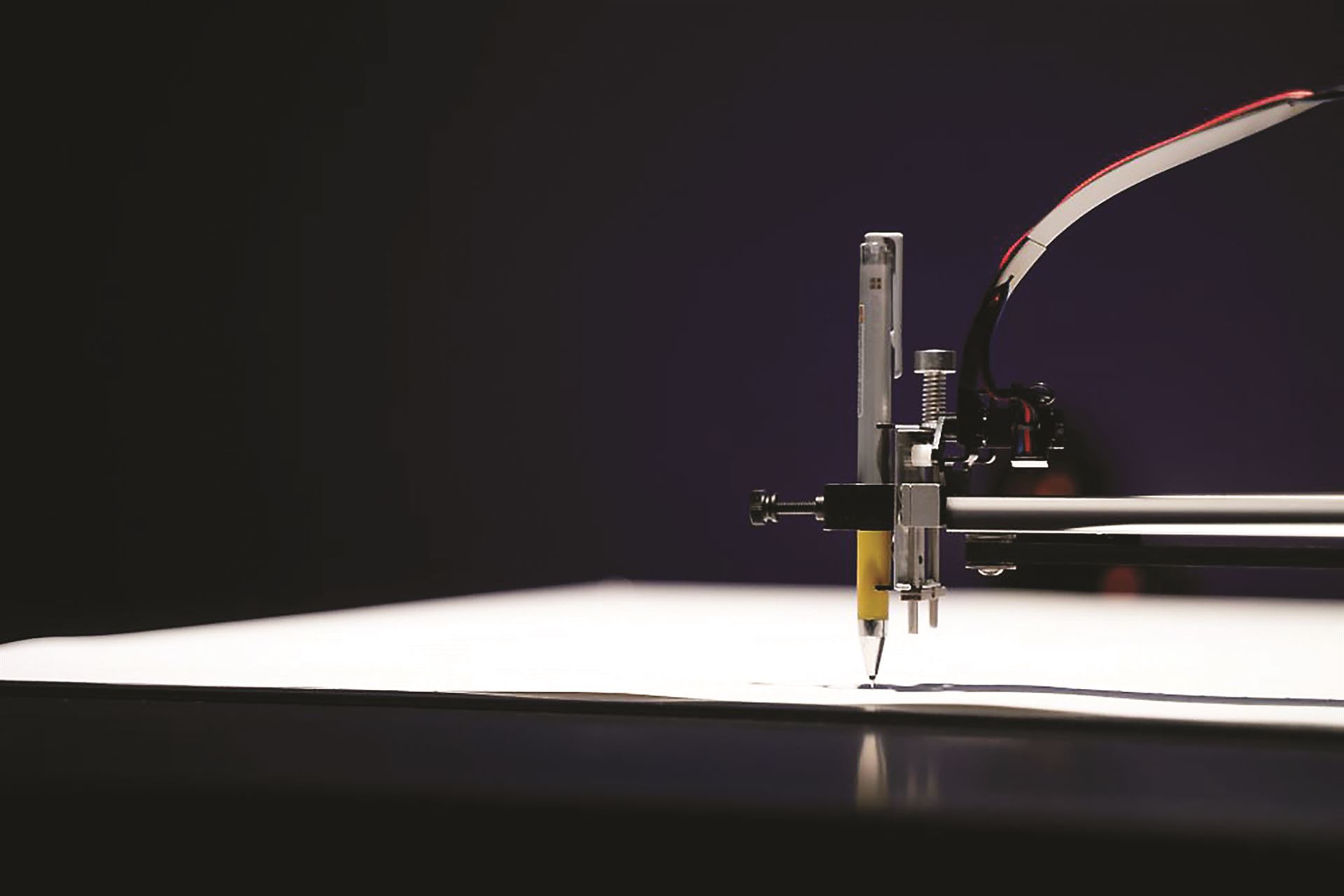

The Machine for Perfect Imperfections installation piece from the Might and Magnificence: Ceremonial Arms and Armor across Cultures exhibition at the City University of Hong Kong’s (CityU’s) Indra and Harry Banga Gallery illustrates how an exhibition based on objects of historical value can take visitors to a completely different place.

It works like this: The machine scans one of the displayed weapons — mostly embodiments of cross-cultural artisanal traditions, made possible because of the existence of the Silk Road. Using a pen plotter, the machine then proceeds to draw infinite parametric images of the errors it has spotted.

Created by Lam Miu-ling, an associate professor at the School of Creative Media at CityU, the piece seems to draw attention to, if not celebrate, the happy accidents that the human hand, as opposed to machines, is capable of.

Libby Chan Lai-pik, the director of the gallery and the show’s co-curator, says that the piece acts as a bridge between the opposing ideas of “ancient craftsmanship and the role of technology in art, using a digital practice”.

The automated artwork and its processes are a result of “new thinking inspired by the patterns, motives and techniques on display at the exhibition,” she adds, applauding the artist for coming up with “a formula for a program that can collect all the information from an exhibit in order to generate new art”.

Filling historical gaps

Sometimes, new-media elements are added to exhibitions because everyone else is doing it. But the inclusion of an audio-visual experience based on a digitized version of a letter from the French monarch Louis XIV (1643- 1715) addressed to the Kangxi emperor (1662-1722) in The Forbidden City and the Palace of Versailles exhibition at the Hong Kong Palace Museum is far from gratuitous.

It fills a real gap in the plethora of exhibits that have been witness to the close association and spirit of cultural exchange existing between France and China since the 17th century, as the physical version isn’t available to display. “The letter is in the possession of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and they don’t lend things. So we have used modern technology to bring that letter, and the friendship between the two rulers, to life,” says Daisy Wang Yiyou, the museum’s deputy director of curatorial, collection and programming. In that letter, Louis XIV had addressed his Chinese counterpart as “our very dear and good friend”, though they had never met in person. “I think there’s a lesson in it,” says Wang.

“We can be friends with people, whoever they are and even if we have never met them. The gesture ties in with Louis XIV’s decision to send missionaries to the Qing (1644-1911) court,” she says, referring to the beginnings of soft power diplomacy between China and France. Illuminated digital sketches are used to rectify a historical error at The Maritime Silk Road exhibition at the Poly MGM Museum in Macao. In the space where the four bronze heads of a monkey, ox, tiger and pig from the Old Summer Palace in Beijing are displayed, the missing eight animal figures of the zodiac are made to digitally reappear on the walls against a digital rendition of the palace courtyard where all 12 sculptures were originally installed around a fountain. It’s a glittering invitation to exhibition visitors to find out about the displayed quartet’s fascinating journey.

Commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor (1736-95) and designed by a French artist, Michel Benoist, the zodiac figures were pillaged when the Anglo-French Allied Forces seized Beijing in 1860.

After the four heads resurfaced at two separate auctions in New York and London in 2000, the Poly Art Museum acquired them and brought them back to Beijing.

Old road, new art

A number of artworks in the exhibition are quite new — results of contemporary artists’ responses to the Maritime Silk Road, or its essence. The exhibition’s curator Su Dan — who is the deputy director of the China National Arts and Crafts Museum, and the China Intangible Cultural Heritage Museum — says that the logic behind putting contemporary art in the same space as centuries-old exhibits has to do with highlighting the Maritime Silk Road’s role as a “continuous conduit for cultural exchange, fostering mutual appreciation and artistic innovation across civilizations”.

“This enduring legacy, spanning from ancient times to the present and extending into the future, is effectively highlighted by juxtaposing historical relics with contemporary art.”

The new works include a social experiment in the form of a gigantic bottle containing hundreds of sealed letters. Lying horizontally on its twin stands, Drifting Bottle — 100 Years by Wu Gaozhong, brings to mind both the seaside souvenir-shop staple — ship-inside-a-bottle showpieces — as well as bottled messages thrown into the sea.

READ MORE: Tapestry of cultural connections

The piece, says Su, embodies “the entire exhibition’s narrative and poses a question for the future”. The letters were sent in response to an open call inviting letters, and will be opened only in 2123. “These letters will await the curiosity of those who come 100 years later, ready to be unveiled and read,” says Su. He hopes that by that time, the piece will have become “a precious historical document that presents the ideological landscape of contemporary people in the future”.

Bai Ming’s Threads of Water Waves reimagines the iconic Chinese glazed blue-and-white ceramic vase with a contemporary twist. A massive cylindrical white glazed ceramic sculpture is covered with innumerable waves of blue lines crisscrossing its surface.

Su says that the piece “draws inspiration from the serene observation of a water surface, featuring abstract, blue ripples that encircle the vessel’s body and extend infinitely. It symbolizes the threads of thought and the expansive, misty waters within human emotional memory”.

Turning full circle

The generic blue-and-white glazed porcelain produced in Chinese kilns was a sought-after commodity in the export market since the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and is still considered emblematic of Chinese high culture.

Ni Haifeng — an artist from Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, who now lives in Amsterdam — uses both the material and the craft tradition of Chinese blue pottery to create new narratives that pay homage to the Silk Road journeys, while also alluding to his own.

His Of the Departure and the Arrival (2005) looks like a random assortment of blue-and-white glazed porcelain sculptures of everyday objects — umbrella, hair dryer, hand-operated pesticide sprayer pump, cycle seat, scissors, and more such.

However, a closer look at the work, on show at the Making It Matters exhibition at Hong Kong’s M+ museum, reveals the presence of history, in the form of a Dutch clog and an elaborate glove, more apposite to a Rembrandt painting.

Ni’s process involves a Silk Road journey of sorts. Sourced in the Netherlands, the objects are cast in glazed porcelain in a kiln in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province. Next, these are painted over with the iconic Delftware blue pottery motifs — which, in turn, were inspired by the traditional Chinese blue-and-white ceramic vases, brought to Europe by the Dutch East India Company long before Delftware began production in the mid-17th century.

Sunny Cheung, a curator of design and architecture at M+, describes Chinese blue and white porcelain — so prized in early modern Europe that it was sometimes fondly called “white gold” — as the “first luxury brand” to be exported out of China.

“Actually, the cobalt that makes up the underglaze blue was introduced to China from West Asia, as a result of the flourishing Silk Road trade,” he adds. It is this two-way traffic between the East and the West that Ni seeks to apotheosize in his creations. Cheung points out that the lotus emblems painted onto Ni’s porcelain sculptures “retain a particularly Chinese style — the repetition of a specific motif rather than many floral perspectives that characterize the blue Delftware style”.

READ MORE: Books, films and everything in between

What makes Ni’s practice even more of a celebration of the Silk Road ethos “is the way in which the items are engineered, so that the finished objects are once again shipped to Delft to complete a process of transformation and historical trade,” Cheung says.

He points out that Ni’s works are about closing a circle in more ways than one, considering “many of the original everyday objects collected by Ni in Amsterdam were likely themselves manufactured in China in places like Shenzhen and subsequently shipped to Europe, so the journey is actually a return of the original objects back to their place of origin before undergoing transformation”.

The more things change …

The more things change … While the use of new art and new media tools to interpret the Silk Road might be some of the obvious ways of courting today’s audiences, another, perhaps slightly overlooked, way of making history relatable is to highlight how some of the practices followed in the heyday of the Silk Road are still useful, if not still in use.

Some examples of how ancient customs not just resonate with but continue into the present in their adapted forms can be found at The Nanhai I Shipwreck and the Maritime Silk Road exhibition at the Hong Kong Heritage Discovery Centre.

Private brewers putting their stamps and marking the year of production on wine vessels — “Liang Zhai Jiu (Liang’s house-brewed wine)” — has parallels with current branding and packaging rituals. A Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) gold foil recovered from the Nanhai I shipwreck is found to be inscribed with the characters Ban Nan Jie Dong Wang Zhu Jiao (an instructor surnamed Wang living in Ban Nan Street East).

Yet another Song Dynasty instance of personalizing currency can be found at Poly MGM Museum’s The Maritime Silk Road exhibition.

A Song Dynasty silver ingot with the name “Zhen” inscribed on it brings to mind presentday nonfungible tokens — authenticated digital assets that come with a unique identity. Curator Su informs that inscriptions like the one found on the silver ingot “typically include information such as the casting date, location, extent of purity, and the craftsman’s name”. “They have traceability and indeed share similarities with the current authenticated digital assets known as NFTs,” he says.