Treasured artifacts from Xinjiang tell a story that extends beyond the Qing Dynasty's imperial court, Wang Kaihao reports.

When Emperor Qianlong (1711-99) ascended the throne in 1735, he inherited a court of wealth and a dynasty reaching its apex. Perhaps that partially explains why this Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) ruler nurtured such affection for fine art throughout his 60-year reign.

Jade, which in Chinese culture represents ritual and dignity, naturally became his focus.

On receiving a treasured jade piece, the emperor, who credited himself a member of the literati, would write a hymn and have it carved into the item.

The present-day Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, particularly around the Kunlun Mountains, is famed for its jade production. Top-tier Hetian (or Hotan) Jade, which is named after the Hotan region, was among Qianlong's favorites.

In the Forbidden City, a story involving the royal court in Beijing and jade, which originated thousands of kilometers away, took on legendary status.

To mark the centennial of the former imperial palace becoming the Palace Museum, an exhibition recalling the saga of jade through 200-odd carefully selected pieces from the storerooms of the emperors is currently underway.

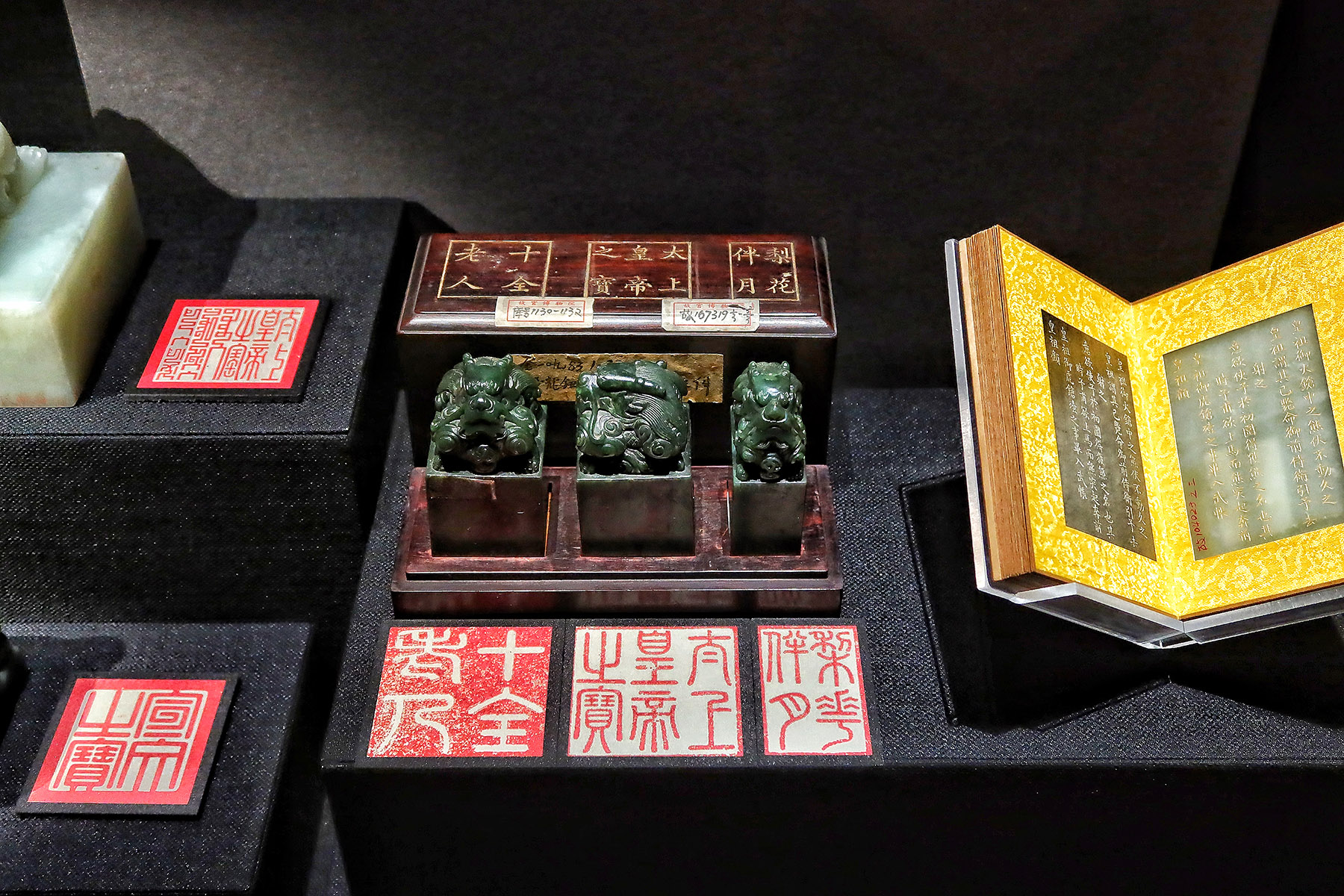

Jade From the Kunlun Mountains: Special Exhibition on Hetian Jade Culture in the Qing Court opened in the Zhaigong (Palace of Abstinence) Gallery on Tuesday and will run for a year. Items ranging from royal seals and ritual artifacts to carvings and miscellaneous articles of daily use demonstrate the versatility of Hetian Jade and the ways it can be transformed under the skillful ministrations of artisans.

"You can see the rich jade culture of the Qing Dynasty," Huang Ying, curator of the exhibition, says. "Hetian Jade is a pillar of Chinese jade culture."

Literati taste

From 1761 onward, Hetian Jade was a presence at the Qing court in the form of biannual tributes in spring and autumn, and became the main type of jade used in the imperial palace, Huang explains.

"The production and use of jade ware underwent a huge advance, sparking another development boom in Chinese jade culture," she says.

As the exhibition shows, Qing imperial jade ware was elegant and refined and became a ubiquitous element in the places scholars worked.

"Jade stationery varies in style," Huang explains. "Some of the pieces were intricately adorned but some were aesthetically restrained. They are emblazoned with decorative motifs that convey a sense of grace."

Representations of six famous intellectuals from the Tang Dynasty (618-907), including renowned poet Li Bai, were carved on a jade writing brush holder to illustrate their daily indulgence in wine, song, poetry, and painting. Qianlong added an inscription to the holder in 1795, whether coincidentally or not, the year he relinquished the throne to his son to devote himself to a retirement of study.

"During the reign of Qianlong, reverence and admiration for antiquity took deep root among the literati," the curator explains. "The emperor himself commissioned numerous archaic jade pieces. … It reflected his pursuit of moral refinement, artistic mastery and a deep connection to the wisdom of ancient sages."

Hetian Jade duplicates of ancient bronze artifacts were produced in abundance for Qing royals. One such example is a dark green jade vase with a fish-waterfowl design on display, the original of which dates back to the Han Dynasty (206 BCAD 220).

As Confucian ideology deeply influenced the values of scholars, people began to attribute gentlemanly benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom and faithfulness to the stone, inspiring the saying that "a gentleman never parts with his jade".

READ MORE: Suzhou's master artisans strive to revive delicate authenticity

Hetian Jade articles of daily use, including dining vessels, chess pieces and perfume bottles also added a touch of class and elegance to the gentlemen of the court. The fashion reached its peak around 1780 as Emperor Qianlong celebrated his 70th birthday. "After all, jade adornment embodied the pursuit of beauty," Huang says.

Tracing the origins

The ritual use of jade dominated China for millennia, and Qing rulers preserved the tradition, using jade for royal documents and seals. Apart from use as offerings in sacrificial ceremonies to heaven, jade was also used to make instruments for musical rituals.

"The Qing court amassed numerous Buddhist statues carved in Hetian Jade," Huang says. "Imperial aesthetics and the distinct features of different ethnic groups were blended."

Nonetheless, the link between the Forbidden City and Hetian jades dates back far before the Qing Dynasty. The collections of Qing emperors merely reflected a millennia-long connection between the jade hub in Xinjiang and the courts of the central dynasties.

Archaeological evidence shows that tremolite jade has been mined in Xinjiang for over 4,000 years to the Neolithic period, Huang adds. Hetian Jade was transported to Central China after the Han Dynasty, the trade booming during the Tang Dynasty. Hetian Jade gradually became the most important material for jade craftsmanship in Central China.

A white jade statue of bixie, a mythical lion-like creature that could ward off evil spirits, is the oldest Hetian Jade artifact in the Forbidden City. Lions are native to Western Asia and North Africa, and images of them were introduced to China via the Silk Road, where they were combined with traditional winged beasts, giving rise to the mythical Chinese creature.

Jade decorations bearing auspicious floral patterns and animal shapes from the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) and an exquisite cup from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) reflect the evolution of Hetian Jade around the rest of the country.

Emperor Qianlong also had his own way of tracing the origins of his treasured stones.

Huang particularly recommends seeing one artifact, a jade sculpture that resembles a miniature rockery, which includes a scene of several men mining jade in a mountain.

Again in 1761, the emperor wrote a poem on the back of the sculpture to honor their endeavors. "It's not only a piece of art, but also a lively witness to history," the curator adds.

"Emperor Qianlong places the use of Hetian Jade on the summit, and the era also left a rich legacy for future generations. The jade exhibits highlight the historical interaction, exchange and integration of Chinese ethnic groups. They are witness to the formation of a shared national identity," says Du Haijiang, deputy director of the Palace Museum.

Cultural exchange

In 1768, the emperor was given a pair of exotic jade plates as gifts. Amazed, he wrote about their origins, and over the ensuing decades, ordered the purchase of many similar jade artifacts from outside China, and had his poems carved on them as well. His Islamic-style "Hindustan Jades" included items not only from northern India, but also from the Ottoman Empire, Central Asia, and even Eastern Europe, says Xu Lin, a jade researcher at the Palace Museum.

"He loved Hindustan Jade so much, he ordered artisans to make duplicates," Xu says.

ALSO READ: Pudong expansion of museum continues apace

Both the duplicates and the originals are on display at the exhibition, so visitors may decipher the variations in artistic style from one culture to another.

Xu says that material analyses demonstrate that most of the Hindustan Jade in the Palace Museum collection is made of stone from Xinjiang.

"Hetian Jade became a link for interaction between China and the world," she adds. "That highlights the openness and inclusiveness of Chinese civilization."

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn