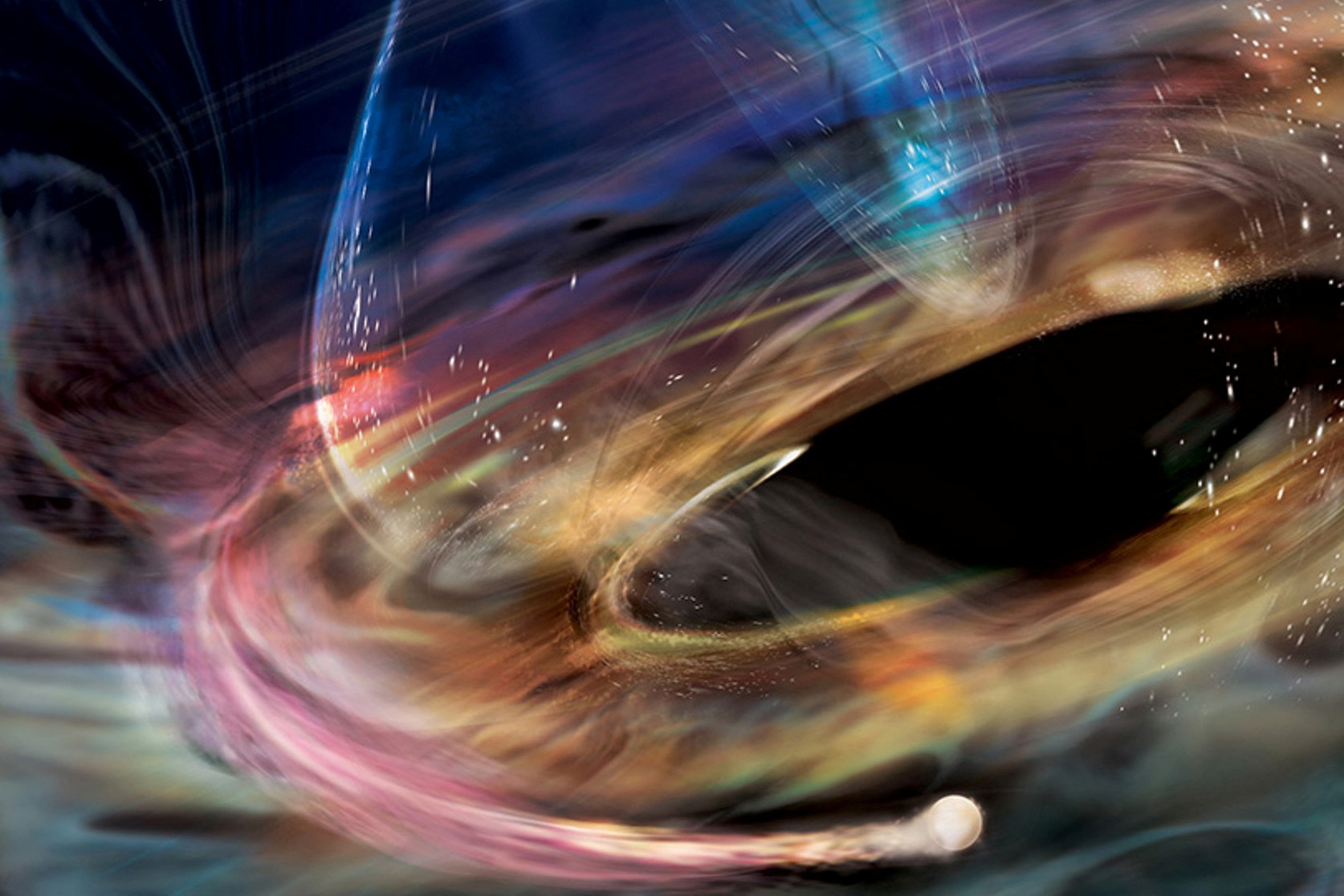

WASHINGTON - Scientists have detected emanating from the nucleus of a galaxy relatively close to our Milky Way flashes of X-rays gradually increasing in frequency that seem to be coming from a white dwarf - a highly compact stellar ember - with a death wish.

The observations made using the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton orbiting X-ray telescope appear to show a white dwarf nearing the point of no return - called the event horizon - as it orbits the galaxy's supermassive black hole, according to the researchers.

"It is probably the closest object we've ever observed orbiting around a supermassive black hole. This is extremely close to the black hole's event horizon," said Megan Masterson, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology doctoral student in physics and lead author of the study that was presented at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Maryland this week and will be published in the journal Nature.

ALSO READ: Moon's bygone magnetic field still present 2 billion years ago

Black holes are extraordinarily dense objects with gravity so strong that not even light can escape. While their immense gravitational strength tends to pull in any objects - such as stars, gas and dust - that stray too close, the researchers said it appears this white dwarf is not making a death plunge but rather has stabilized its orbit around the black hole.

The galaxy is located about 270 million light-years from Earth. A light-year is the distance light travels in a year, 5.9 trillion miles (9.5 trillion km).

Most galaxies have a large black hole at their core. The mass of the black hole in the new observations, called 1ES 1927+654, is about a million times greater than the mass of our sun. The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, called Sagittarius A*, is about four times more massive than this one.

READ MORE: NASA spacecraft 'safe' after closest-ever approach to Sun

White dwarfs are among the most compact objects in the cosmos, though not as dense as a black hole. Stars with up to eight times the mass of our sun appear destined to end up as white dwarf. They eventually burn up all the hydrogen they use as fuel. Gravity then causes them to collapse and blow off their outer layers in a "red giant" stage, eventually leaving behind a compact core roughly the diameter of Earth - the white dwarf.

This one appears to have a mass about 10 percent that of the sun, traveling at nearly half the speed of light. It is traversing the extremely high-energy environment around the black hole and producing X-ray flashes as it orbits in this environment. The flashes initially became shorter and shorter, declining from every 18 minutes down to seven minutes over a period of about two years, as the white dwarf was drawn ever closer to the black hole and the size of its orbit diminished, but then stabilized.

The researchers estimated that the white dwarf is orbiting the black hole at about 5 percent the distance that separates Earth from the sun, or a bit under 5 million miles (8 million km).

READ MORE: Webb telescope confirms the universe is expanding at an unexpected rate

They said its orbit is stabilizing perhaps because the outer layers of the white dwarf are being sucked into the black hole, providing a kick-back action preventing the object from crossing the event horizon and facing oblivion. The white dwarf actually may be able to survive this close encounter, they added.

Scientists may be able to confirm that this is indeed a white dwarf using next-generation observatories such as NASA's Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), which is designed to detect ripples in space-time called gravitational waves.

"What's so fascinating about this result for me is that it suggests that objects can orbit very close to supermassive black holes, and so I'm hopeful for joint detections of these objects in both X-ray light and in gravitational wave emission, with LISA that's set to launch in 2035," said MIT astrophysicist and study co-author Erin Kara.