Chinese musical groups based overseas are elevating Chinese art and culture on the world stage, acting as cultural messengers and bridging East and West. Wang Yuke reports.

As The Voyage of the Silk Road crescendoed to its peak, those familiar with Chinese regional culture might have found themselves haunted by the image of the rugged expanse of Shaanxi province’s plateau — the earthy ocher sediment swirling in the air — where its capital city, Xi’an, is renowned as the starting point of the Silk Road.

The enlivening musical piece being performed in London for the first time was presented by an ensemble of emerging musicians from New Elements Music and elsewhere, the majority of those from the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong. The concert co-organizer, which was formed in the United Kingdom in 2019, is committed to providing a platform for young people with musical talent to express themselves, while fostering cross-cultural collaboration worldwide and displaying the ingenuity of Chinese musical heritage.

The prevailing stringed instruments, while harmonizing with their Chinese counterparts, evoke the sound of bells tinkling around the neck of an industrious camel. This musical motif echoes the 18th-century clay camel, proudly displayed at the center of the Silk Roads exhibition at the British Museum. The ancient transport animal, in glistening ocher with a touch of emerald green, rears its head, while bolts of silk balanced securely on its humps speak to the unshakeable power of the Chinese invention — silk — economically, commercially and culturally.

READ MORE: Maestro brings ancient Chinese sounds to London

The musical and visual cues forge a resounding echo chamber of applause for the ultimate cultural cross-pollination achieved on the Silk Road. Silk served as a unifying thread, catalyzing interchange between diverse cultures and rendering the flourishing of civilizations in tandem. Yet, the Silk Road was far from an ephemeral flourish in the narrative of human civilization. It has outlived the earliest significant forays into cultural exchange, baked into every economy’s cultural and social growth formula, informing and culminating in colossal transformations over millennia.

Evoking cultural echoes

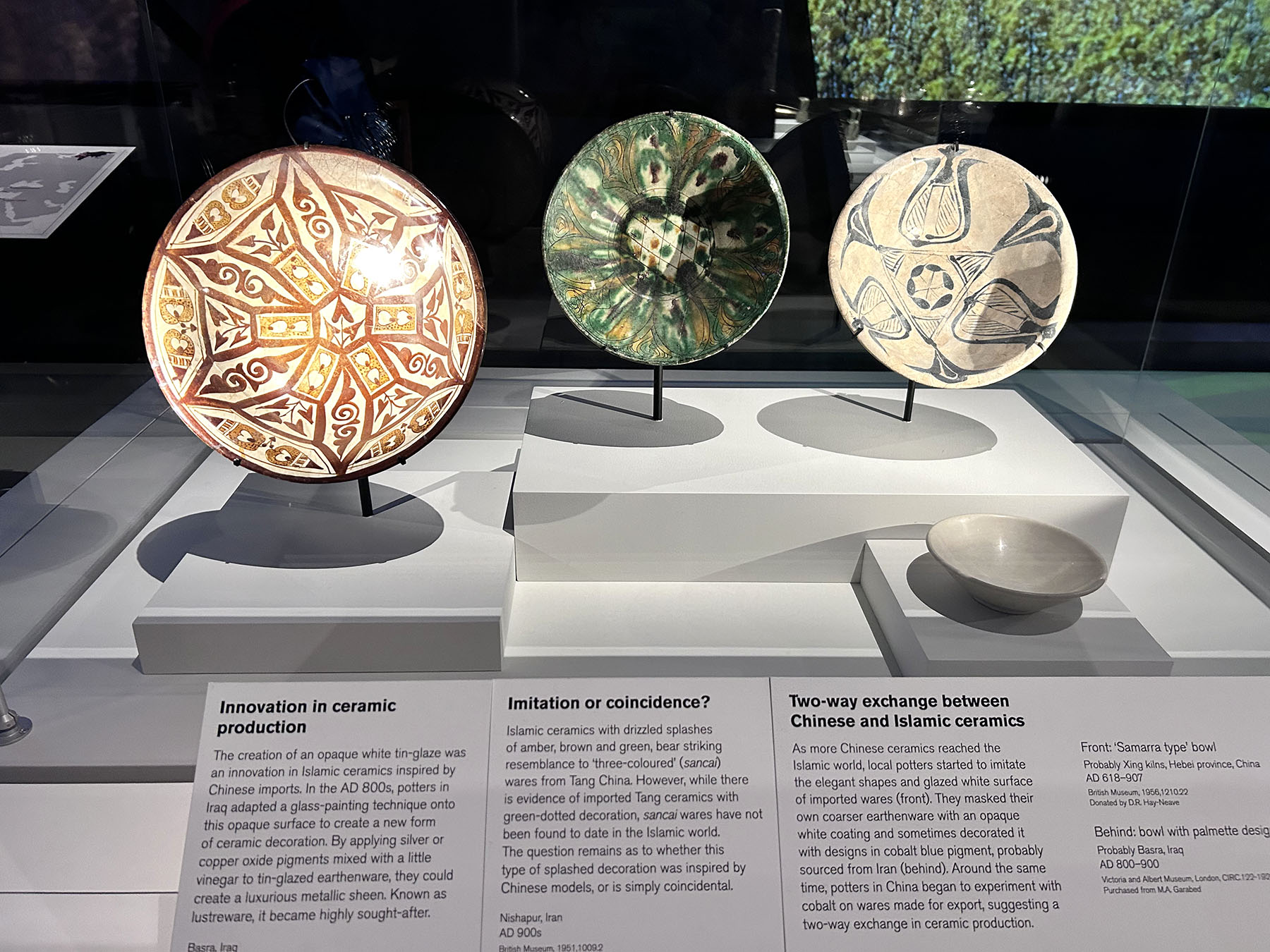

The exhibition at the British Museum explores 500 years of Silk Road history (500-1,000 AD) across five geographic zones from East to West, highlighting a wealth of Chinese ceramics, exquisitely sturdy textile and sculptural relics, and the heft of silk as cultural and economic currencies.

The concert by the overseas musical troupe and the crowd-pleasing pivotal exhibition of the year at the British Museum both weave their shows with Silk Road yarn. This is hardly coincidental as any discourse on multicultural synergy cannot proceed without roping in the well-trodden route of silk, and remains incomplete without recounting the cultural input and imports from China.

The sumptuous and humane tune rendered on Chinese classical orchestral instruments — guzheng, erhu, pipa and dizi — in The Voyage of the Silk Road might be redolent of the unbridled yet grounded energy of Qinqiang Opera, accompanied by the rhythmic pulse of the drum. It’s as though the very dust and grit of the land infuse the music, channeling its energy to the listeners and urging them to rise and dance off the ground.

Since Qinqiang Opera is performed in the Shannxi dialect, it can be said that The Voyage of the Silk Road is redolent of regional dialectic undertones.

“The craftsmanship of the guzheng enables each note to be subdivided into microtones, creating a nuanced sound that mirrors the tonal system of dialects,” says guzheng player Ji Mengdie. After all, guzheng was invented for that very purpose.

Among the repertoire, The Voyage of the Silk Road and Silk Road: To the West stand out, handpicked to embody the Silk Road’s spirit — audacious, trailblazing, resourceful, and contemplative, fostering connection and exchange.

The Voyage of the Silk Road was the brainchild of Ray Lin, a young musician and also the conductor of the concert with an international background, which equips him with an East-West fused artistic prism and cultural mindset aligned with the theme of the Silk Road, says Adrian Wang Yuzhe, founder of New Elements Music and chief director of the concert.

As Silk Road: To the West reached its climax, engrossing melodies — enchantingly resonant — chimed from the erhu and guzheng. They faded in, unfurled, and extended into the distance, as if echoing into the mystery-shrouded horizon, until joined by the chorus. The congruent cadence exuded in the piece, composed of thundering Chinese drums and the triumphant suona, conjures an image of cultural evangelists traversing the Silk Road — unearthing, exchanging and reinventing. The musical trajectory not only draws from the catchy melodies of the classic novel’s theme songs, Dare to Ask Where the Road Is and Immortal Sound Above Cloud Palace, as familiar ears find themselves humming along, but also charts the Silk Road expedition in a musical nutshell, balancing narrative precision with fantastical embellishment.

The expedition musically portrayed here elicits the image of the massive embroidery in faded beige tones, commanding attention as a show-stopping monolithic craft in the museum, inviting visitors to engage in an intimate examination of its intricate, velvety silk threads sewn onto a silk ground backed with hemp. This extraordinary piece, unearthed from the Mogao Caves — 25 kilometers southeast of Dunhuang’s city center — stands as a precious relic from a sacred religious and cultural crossroads along the Silk Road in Gansu province. The wear and tear at its periphery does not compromise the fineness exhibited by the ancient crafty hands. Neither do the finery, endurance, and versatility of silk, which has held this chunky piece together for at least 14 centuries.

Back to the musical rendering, the lyrics in Silk Road: To the West ring a bell for those aware of the classic Chinese novel-adapted TV drama — a staple of school holiday television that has accompanied generations of children. “Dare to ask where the road is? The road is beneath your feet ...” In this nostalgic and celebratory tribute to the cultural grandeur of the Silk Road, these musical threads ripple through both the initiated and uninitiated in Chinese traditional art and culture, as the words of wisdom seem to transcend the past, present and future, carrying their timeless resonance across generations and nationalities.

The “cherishing heritage through innovation” — the very DNA of the Silk Road ethos — gets imprinted and reinforced in the concert, notes Wang. In Silk Road: To the West, for instance, contemporary and futuristic drama is added to the creation and performance, says Ji.

“In composition and arrangement, we integrate traditional Chinese folk music with a large orchestra, adding choral elements to create a richer and more layered auditory experience. This arrangement style is quite rare overseas and brings a fresh expressive power to traditional Chinese music,” says Wang.

The Chinese musical instruments played in the concert, which are faithful to their artistic origins and infused with a modern twist, are a literal reiteration of New Elements Music’s message that “traditional does not mean ancient”, contends Ray Lin. The traditional music equivalents of paintbrushes do not merely exhibit an expansive scale of timbres, pitches and notes so, as a result, can bleed an all-encompassing spectrum of emotions into the audio canvas.

Every Chinese instrument struts its spectrum of persona in the concert: Erhu’s wistful, murmuring tune whispers the melancholic sentiment, serving as the poignant weepy vessel for the emotion.

As the most captivating vignette, referencing the childhood fictional TV drama Journey to the West, unfolds in Silk Road: To the West, a rich interplay of instruments takes center stage. The dominance of violin, viola and cello intertwines with rhythmically crisp and bouncy melodies, accentuated by the affecting tail sounds of a dexterous pipa skim. These elements coalesce with the narrative-driven guzheng and the choir’s humanizing touch. The mood-setting flow of Western strings, married with the mood-embellishing Chinese plucked instruments, together evoke a vision of pioneering avant-gardes and cultural missionaries navigating the crucibles of the Silk Road.

While the consummate meshing of Western and Eastern instruments as a wholesome ensemble captures the essence of a Chinese mythical volume, it also serves as a conduit to channel exoticness, casting a veil of haunting mystery and immeasurable possibilities over the Herculean Silk Road odyssey telegraphed in The Voyage of the Silk Road.

Going against its often-exploited association with poignancy and homesick sorrow, the dizi in Dance of the Golden Snake takes center stage in a celebration of festivity, vitality and prosperity. This striking shift speaks volumes about the deceptively simple Chinese bamboo flute’s complexity in conveying emotional figures of speech.

Orchestrated as a reverential tribute to the Silk Road and China’s indelible imprint on large-scale cultural exchange and integration, the concert doubles as an introductory program to traditional Chinese music and its rich vault of instruments — an endeavor Wang hopes will help dispel Western lack of knowledge of Chinese art.

The West’s limited awareness of traditional Chinese music both deflates and worries Wang and the young artists of the ensemble. Yet, these emerging cultural ambassadors transform this daunting illiteracy into a motivation to sound to the world that the finesse of these traditional musical inventions outlasts their golden era in antiquity — thriving through relentless reinvention and innovation, even as typical Western instruments continue to dominate in recognition, and artificial intelligence gains rivaling momentum.

“Western audiences show a keen interest in traditional and classical Chinese music though their understanding of it remains limited. This curiosity is an assuring opportunity for us to demonstrate the depth and diversity of Chinese culture through music, forging a bridge for cultural exchange between East and West,” concludes Wang.

Bridging musical worlds

Chinese stringed music boasts the iconic unparalleled “yun” — an elusive term in Chinese with no precise equivalent in English due to its rich layers of meaning, says Ji. The “yun” in guzheng, in particular, refers to a melodic tune and penetrating rhythm that not only pleases the ears, but also stirs the heart, evoking memories of the past or a figment of one’s imagination. One could borrow the concept of “aftertaste” in food to better comprehend the “yun”.

But how is “yun” created? Technically, vibrato, string bending, pitch pressing, and the attack on the string to release the initial note are among the common techniques that leave a “yun” behind, says Ji. She explains that most “yun” emanated by vibrato on the guzheng is executed by the player’s left hand, which commands over 100 varieties of techniques, while the tone-setting or drama-foregrounding attack on the first note is usually the job of the right hand. The enchanting echoing chamber effect, unique to the guzheng, is birthed through the artful manipulation of the fingers. These movements evoke the fluidity and grace of ballet techniques such as en pointe, pique, and battement frappe, as well as gliding, brushing and pinning motions.

ALSO READ: Singing in a new year of musical exploration

The emotively charged and fluid musical substitute for pedestrian daily speech and storytelling is imbued with an exceptionally “narrational”, “conversational” and “poetic” sentiment, says Lin. “This sentiment is flexed and achieved, thanks to the guzheng’s large resonance cavity.”

“We’re not a Chinese ensemble stationed overseas, but rather an international music organization dedicated to promoting Chinese classical music domestically and abroad,” says Wang, defining New Elements Music. “Our endeavor of spreading Chinese music language far and wide derives from both a deep passion and affinity for our cultural heritage and a sense of obligation — to elevate the presence and representation of Chinese music on the global stage.”

This ambition and sentiment are zestfully echoed by violinists Du Qiujia from the Chinese mainland, and Lam Hong-ting from Hong Kong, both of whom initially traveled overseas to study, driven in part by their goal of becoming “cultural messengers between East and West”.

The concert has ended. The exhibition has concluded. But the story of the Silk Road — and the path painstakingly laid for future generations to explore and expand — will live on for good.