Secret Chinese script once shared among women finds renewed resonance, Hou Chenchen reports.

One evening in 2021, Li Ruoxi, 22, whose English name is Rosie, was scrolling through short videos to seek inspiration for her art designs. Suddenly, a song in an unfamiliar language played through her headphones. She could not understand the lyrics but found herself moved to tears.

Back in 1993, Feng Jingsan, who collects cultural items, stumbled upon a bronze coin dating to the 19th century in an antique market. The coin was engraved with eight unusual, willow leaf-shaped characters, whose meaning he could not make out.

READ MORE: Women's voices spill out of Hidden Letters

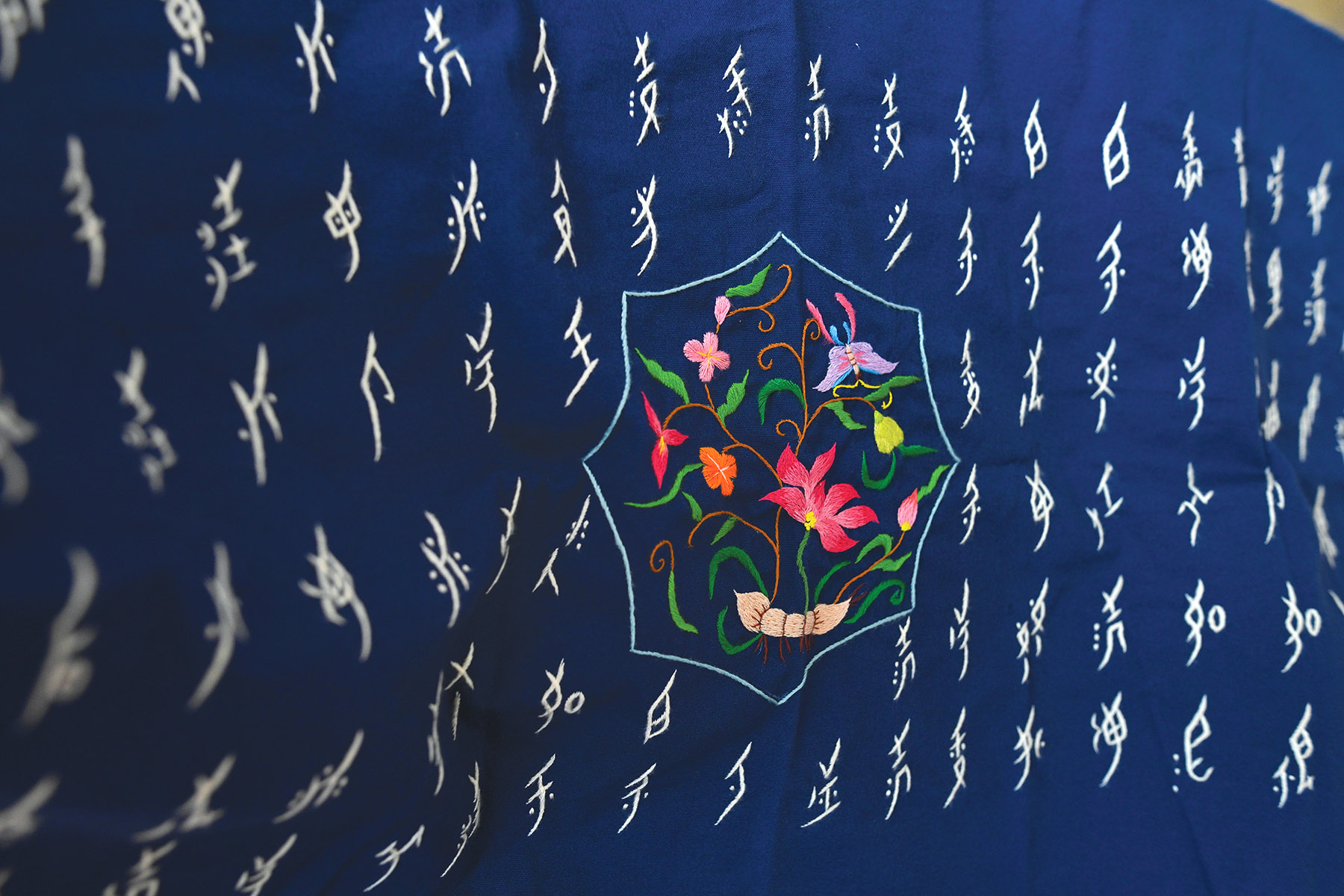

Their shared curiosity led both Li and Feng to get to know an extraordinary language — nyushu, the world's only gender-specific script of its kind, created by and for women. The unique writing system can be traced to Puwei island of Jiangyong county, Yongzhou city, Central China's Hunan province.

Li eventually learned that the song she heard was about a woman confiding in friends about the struggles of marriage and family life.

Feng, meanwhile, deciphered the coin's inscription as, "all women under the sun are sisters".

Though the exact origins of nyushu are unclear, several villages in Jiangyong, among the Han and Yao ethnic communities, are recognized as being crucial to its preservation and development.

Historically, literacy in China was largely reserved for men, and women were often denied access to formal education. Women who were formally educated typically came from the urban elite.

The content of nyushu works are mainly drawn from women's everyday lives — marriage, family, social interactions, anecdotes, songs and riddles. Through a set of codes that were incomprehensible to men, the special language allowed many women to communicate freely, sharing their innermost feelings through songs, poetry and secret letters to one another.

As modernization swept across China and more women were able to access education, the relevance of nyushu dwindled.

When nyushu began to garner more attention in the early 1980s, with just two elderly women found to write it proficiently, the script teetered on the brink of obscurity.

The death of centenarian Yang Huanyi in 2004 marked the start of a post-nyushu era. Yang was considered the last of the nyushu users raised amid its cultural backdrop, practicing it in daily life.

But the script's decline also drew attention across various fields. Nyushu workshops in Jiangyong sparked renewed interest, introducing more people to the cultural treasure. In 2006, the State Council listed nyushu as national intangible cultural heritage. A nyushu museum was established on Puwei island in May 2007, further preserving it for future generations.

Nyushu is now finding new resonance among a generation of young women. Through exhibitions, field trips and community building, they are breathing new life into the unique language and transforming it from a cultural relic into a vibrant symbol of modern female expression.

Reviving language

Two years ago, Li met Hu Xin, now 36, who helped promote nyushu at its Puwei museum. Hu is the youngest designated inheritor of the script, following support from the authorities to help preserve it. In 2000, Hu, her mother and her sisters attended evening classes to learn nyushu. Hu subsequently became a guide at the museum.

"When I started working at the museum 15 years ago, nyushu was so niche that even many local women didn't know about it," Hu recalls, noting how challenging it was to learn the language from scratch.

She had to memorize two to three characters each day from a dictionary compiled by researchers before the last native users died.

Hu's favorite line in nyushu poetry is, "men are said to have great ambition, but women are just as excellent".

She says that she believes the revival of nyushu is deeply tied to the idea of "women's empowerment", championed by young women like Li.

When Li was preparing for her graduation exhibition at the Cambridge School of Art under the United Kingdom's Anglia Ruskin University, her desire to delve deeper into nyushu and bring it into contemporary art led her to Puwei island for field research.

"Setting foot on the rich land of Jiangyong, I finally understood why so many nyushu songs celebrate nature," Li says.

Growing up in a small town between cities and rural areas, she described herself as "a bridge between the broader modern world and rural traditions".

"Women's inner worlds are incredibly powerful; when others connect with their hearts, there's a brightening effect," she says.

"Nyushu isn't about external confrontation. Instead, it celebrates the beauty of quiet communication among women."

For her exhibition, Li designed an installation where letters glimmer gently in a dark, quiet space, visible only as viewers draw near.

"Her work is both intensely personal to the quiet viewer, and so universal that you could not detect the artist's nationality," said Philip Ward, fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in the UK, while reviewing Li's work. "Her work is confined neither to her time or place but is eternal in its wisdom and beauty."

From a confidential women's space, nyushu is certainly becoming a "global culture that belongs to the world", leading composer Tan Dun said in a previous interview in 2018.A Hunan native, he has composed several works on nyushu.

Bonding together

Through her research, Zhang Luli, an associate professor at South-Central Minzu University in Wuhan, capital of Central China's Hubei province, has also witnessed a rise in the popularity of nyushu culture on social media since March 2023, encompassing a community of young female artists and enthusiasts.

Women aged 18 to 30 form a closely knit nyushu community, connected through social media, according to Zhang.

"Their work captures the vitality and independence of modern women," she says. "They are bringing contemporary life into this intangible cultural heritage, revitalizing and transforming nyushu."

In Jiangyong, Ma Bingyu, 17, a nyushu enthusiast from Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, celebrated a unique coming-of-age ceremony. Dressed in traditional attire, she marked the milestone with the melodies of nyushu songs.

This summer, Li and Wang Zilu, a graduate of the Chelsea College of Arts at the University of the Arts London in the UK, connected online and set out together on a field trip to Jiangyong to immerse themselves in nyushu culture.

In recent months, they have been part of a group of nyushu explorers looking at the theory and case studies of the script, including those involving aesthetics and community art. With shared interests and unique perspectives, they journeyed to Jiangyong to engage directly with nyushu inheritors in their home environment.

Reflecting on the experience, Ma says: "For me, nyushu isn't just a way of writing; it's a bridge connecting women's emotions and friendships. The girls and I curated an exhibition centered on nyushu's charm, an important way to share and preserve this culture."

Ju Haibo, 23, a student pursuing her master's degree at Dublin City University, Ireland, says: "Nyushu has opened a narrow but promising path. As we connect with each other, we heal together and feel seen and understood. I experienced a sense of inclusivity and happiness that I hadn't felt in a long time."

"I met wonderful people and felt a belonging I had long been seeking," says Tian Shuyu, 20, a student at St. John's University in the US.

After years of traveling in search of connection, both Tian and Ju often felt a sense of loneliness and found it difficult to build deep relationships. But on their trip to Jiangyong, they discovered how naturally emotional connections can arise.

For Man Wenxi, 20, a student at South China University of Technology in Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong province, learning nyushu became a journey of discovering other women's experiences as well as her own identity.

"Women's souls across generations and identities are converging, growing into a shared spiritual space where we can express ourselves freely," Man says.

"It's in this space that my design work comes to life."

ALSO READ: Women's written language gets boost

Wang reflected on how nyushu inheritors weave vibrant threads into bands and garments that enrich their daily lives, threading in the joys, sorrows, passions and hopes of life.

"We honor their wishes, once whispered, with art that breathes in the present, alive in its making," she says.

Sang Yihan and Gao Yuxi contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at houchenchen@chinadaily.com.cn