From ancient stone tools to volcanic landscapes, explore the beautiful natural and cultural heritage that defines the Olorgesailie site

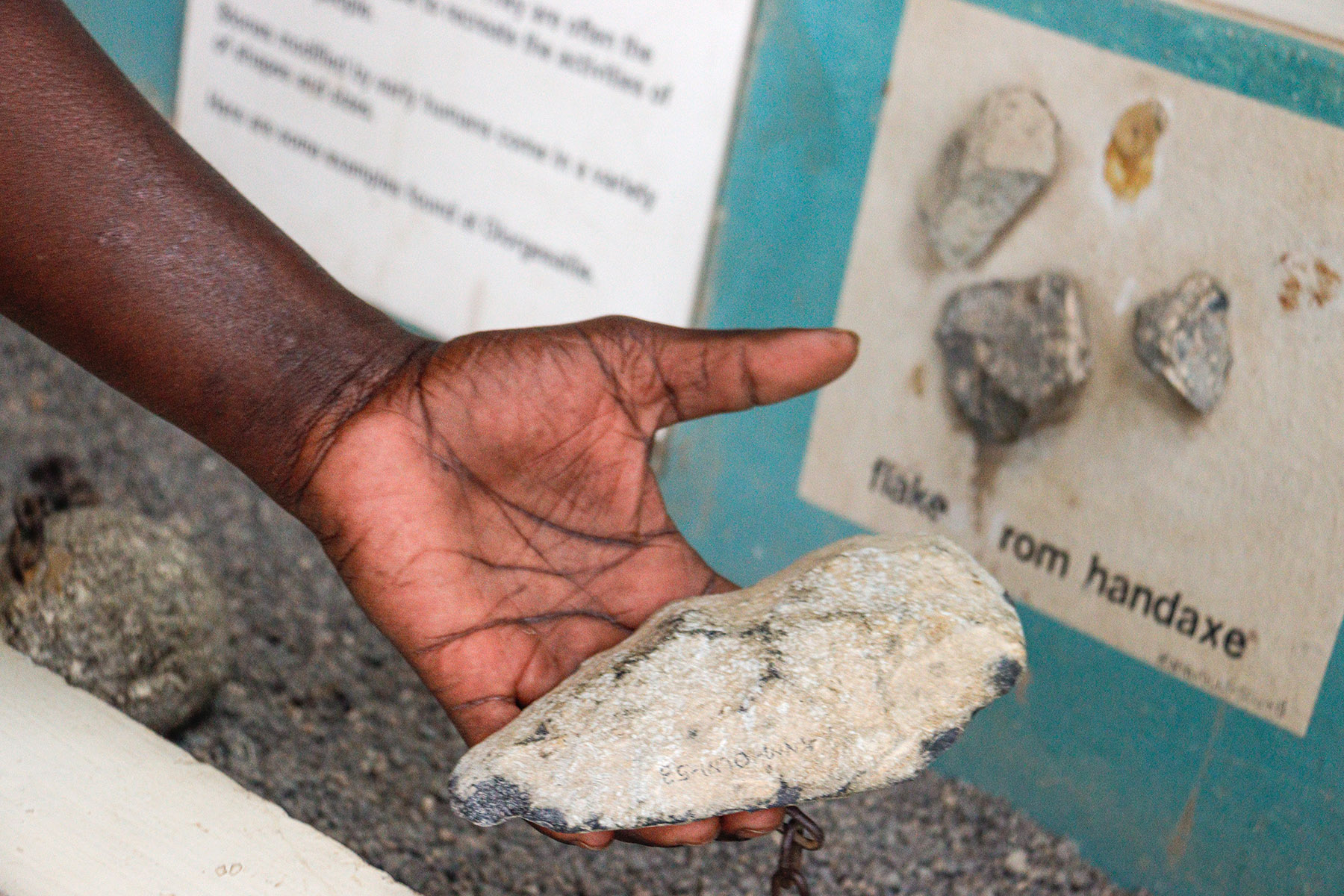

Located 90 kilometers southwest of Kenya's capital Nairobi lies the Olorgesailie Prehistoric Site, dubbed the world's "factory of stone tools".This title stems from the large concentration of ancient tools, specifically hand axes, unearthed at the site, which date back millions of years.

Spanning an area of 50 hectares in the Great Rift Valley, between the extinct volcanoes of Mount Olorgesailie and Mount Oldonyo Esakut, the site is a memorable experience, rich in historical significance, and draws archaeologists, paleontologists, geologists, and visitors with a passion for human evolution.

Olorgesailie is a trove of in situ prehistoric materials, including hand axes, armor stones, flakes, and bones from extinct species of hippopotamus and elephant, deposited more than a million years ago.

READ MORE: It takes a team to reach summit of Kilimanjaro

Robert Opuka from the National Museums of Kenya based at Olorgesailie says the site has been revealing prehistoric materials since 1919, when British geologist John Walter Gregory discovered hand axes near Mount Olorgesailie while exploring for minerals in East Africa.

In the 1940s, British-Kenyan paleoanthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey conducted the first excavations at the main site following Gregory's notes, unearthing more hand axes. Later, in the 1960s, South African archaeologist Glynn Isaac expanded research through further excavations and geological studies as part of his dissertation.

Opuka says the artifacts found at Olorgesailie are associated with Homo erectus, an early human ancestor, based on sedimentary dating.

"Isaac carried out a lot of archaeological work around understanding the behavior of Homo erectus and the surrounding environment. He also produced a lot of documentation in regard to Homo erectus in Olorgesailie, Turkana, and the Omo River in Ethiopia," he said.

After Isaac's death in 1985, the site remained largely dormant until the late 1980s, when Richard Potts, director of the Human Origins Program at the Smithsonian Institution in California, took up the work, Opuka says.

Since then, the institution has partnered with the National Museums of Kenya to conduct excavations and geological studies.

Opuka says research into the ways early hominins used the land and responded to environmental changes takes place every year in July and August (Kenya's winter), when weather conditions are more favorable.

"Through collaboration with other private institutions and the United States government, the Smithsonian Institution mobilizes funds to support research work," he adds.

Although many artifacts and faunal remains have been unearthed at the Olorgesailie Basin since 1942, only one hominin remain — a frontal bone — was discovered in situ in 2003, raising questions about where exactly early humans lived.

According to an article published on the Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program website, Potts and his team believe they may have lived in the highlands around Mount Olorgesailie, because no hominin remains have been found in lowland sediments.

"The research is ongoing and we may not know what the next big surprise will be," Opuka says. "We have a lot of expectations."

The site is popular with schools and institutions, especially scientists and archaeologists, as well as with people interested in learning about human evolution.

"Our peak season is July and August, when many schools organize student visits for practical learning, as opposed to other months when temperatures are high," he says.

The site is believed to have been a lake about 180,000 years ago. However, because of volcanic activity, the lake has since disappeared. Over time, rain and wind eroded the sediment and buried traces of animal and human activity deep beneath the surface.

Several sites used for butchering animals, marked by a concentration of hand axes, other stone tools, and bone fragments of extinct animals deposited more than 100,000 years ago have been discovered.

Opuka says the lake once attracted wild animals, including extinct species of hippo, zebra, elephant, baboon, and giraffe.

Fossils indicate that large baboons and zebras were especially abundant in Olorgesailie between 1 million and 700,000 years ago. Many of these species probably became extinct around 300,000 years ago.

To protect the archaeological and paleontological materials from both human interference and natural degradation, a raised wooden platform has been constructed. This allows visitors to explore the site without disturbing the remains.

'Incredible visit'

Christina White, a distant cousin of Mary Leakey, visited the Olorgesailie site on Jan 10 and described it as "incredible", calling the sheer number of hand axes found there extraordinary.

"You don't see that anywhere else. What's lovely to see is that all the axes, whether they come from Europe, China, probably anywhere, are roughly the same shape and are made roughly the same way, with different stones, but mainly, flint," she says.

White adds that while at other archaeological sites, it is presumed that early humans traded stone tools and took them with them as they traveled, it appears that at Olorgesailie, they discarded the tools they made.

"I know they are heavy, so you wouldn't want to carry too many, but that's unusual in itself. It's like they may have killed one animal and then dropped them, and then quickly made another when they had to kill another animal. So, it's fascinating," she says.

Apart from her interest in seeing the tools, White also speaks about imagining how Homo erectus behaved and lived while walking around the site, how the area would have looked when the lake existed and there were rivers flowing into it, as well as the thought that she may well have been walking on buried artifacts.

One of the excavation sites produced a humerus, or upper arm bone, of an extinct elephant species that was more closely related to the Indian elephant than to the modern African elephant. The bone is larger than that of the modern African elephant.

Specimens from Olorgesailie are among the last known bones of this species, which existed nearly 3 million years ago and became extinct about 600,000 years ago.

White says it was interesting to learn that the extinct elephant was more closely related to the Asian elephant, and that it was significantly taller and had smaller ears, much like modern Asian elephants.

She speculates that African elephants may have evolved from their Asian counterparts, developing larger ears to help regulate body temperature. Additionally, they may have become smaller in size because of the extreme heat of the region.

Regarding the hippo fossils, White says that while it remains unclear whether they were killed or died naturally, it is possible that early humans used their skins to make baskets or fishing implements.

White, who was visiting Kenya for two weeks to attend the 60th wedding anniversary of her Nairobi-resident uncle, said that he had encouraged her to visit Olorgesailie.

She had previously visited Olduvai Gorge, a paleoanthropological site in the eastern Serengeti Plain of northern Tanzania, which is famous for the discoveries of hominin fossils by Louis and Mary Leakey.

White speaks about visiting Mary Leakey when she was in her 20s. She said that Leakey, who was in her 70s at the time, had a deep influence on her life.

She also expressed her desire for a story about the Olorgesailie Prehistoric Site to be published in a widely read international magazine dedicated to archaeology, such as Current Archaeology or World Archaeology, to raise global awareness of the site's significance.

Bringing the story to life

Danson Taris, an Olorgesailie native who has worked as a tour guide at the site for the past seven years, considers himself fortunate to be able to bring the story of human evolution — something he first learned about in school — to life.

"It has been an interesting experience, learning from scientists and professors who come to do research from the site. I have also expanded my network of friends," he said.

Although Taris was unable to pursue higher education after high school, he said that securing a job at the site has been life-changing.

In addition to ancient remains and interacting with the environment once inhabited by early hominins, visitors to Olorgesailie can participate in activities like mountain hiking, baboon watching, and visiting nearby Lake Magadi, 45 kilometers away.

The site partners with the Olorgesailie Conservancy to facilitate mountain hiking.

Climbing Mount Olorgesailie, which rises to a height of 1,760 meters, takes about three hours up and another three down. Best begun at 5 or 6 am to avoid the heat, the hike involves navigating rocky trails and thorny bushes.

According to the National Museums of Kenya, the mountain is named after a Maasai elder who used it as a place for meditation and meetings with village elders.

There is a campsite, but visitors need to bring their own camping equipment. Firewood can be purchased from Maasai women, who also sell beaded necklaces.

There are also eight round, thatched self-service huts- called bandas in East Africa — for those who prefer not to camp. Four have twin beds, while the other four have single beds.

Just a kilometer from the site, visitors can watch baboons gathering for the night at a "baboon camp" at around 5 or 6 pm. It is also an excellent spot for birdwatching.

Pink-tinged Lake Magadi

Another key nearby attraction is the scenic, pink-tinged Lake Magadi, an amazing destination for landscape photography, filmmaking, adventure camping safaris, and bird-watching, especially flamingos.

The lake's reddish hue is the result of chemical reactions between algae and the salt in the water.

Lake Magadi is also popular for its soda ash and hot springs, where visitors can bathe in water believed to be therapeutic. As no perennial streams flow into the lake its water is mainly replenished by these saline hot springs.

ALSO READ: The famous gate to 'hell'

According to Australia's Saltwork Consultants, Lake Magadi contains more than 30 billion metric tons of trona (a sodium bicarbonate compound that can be processed into soda ash or bicarbonate of soda) in a bed between 7 and 40 meters thick. The lake is believed to have formed over the course of the past 9,000 years as a result of volcanic activity and high levels of precipitation in the Great Rift Valley region.

Trona has been mined at the lake since 1914, and the facility currently owned and operated by Tata Chemicals Magadi produces 350,000 tons of soda ash per year, according to Saltwork.

The thermal springs driven by the area's volcanic activity are the primary source of salt in the lake, and the water arises from a deep, actively circulating groundwater reservoir.

In addition, visitors can experience the beauty of Maasai culture by staying in Maasai villages, visiting Maasai homes, and sampling traditional meals, which will give them an insight into a community that has retained its traditions, lore, and lifestyle.