Italian Sinologist delves deep into visual art form, searching for its true legacy and historical value, Fang Aiqing reports.

In the spring of 2019, upon his departure to Shaoxing in East China's Zhejiang province, Italian Sinologist Pietro De Laurentis explained to his mother that he was about to attend a Chinese calligraphy-themed seminar held in the hometown of "China's Leonardo da Vinci".

The professor of Chinese calligraphy history at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, Guangdong province, was referring to Wang Xizhi, a calligraphy master and intellectual from the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420). To the Italian scholar, Wang and da Vinci both represent their time and culture and expressed admiration and curiosity for the truth of nature in their improvisational creations.

READ MORE: Sculpting the imagination

Unfortunately, no confirmed authentic works of Wang have survived and the reliability of the some hundred ancient copies remains an inexhaustible research topic. Throughout history, the charm of Wang's calligraphy has been marveled at, accompanied by mysteries akin to those left by da Vinci.

Despite this, De Laurentis, 47, is just one of numerous determined admirers searching for traces of Wang's true legacy within the great canon of historical archives, and he has indeed found a destination — the Xi'an Beilin Museum in Northwest China's Shaanxi province.

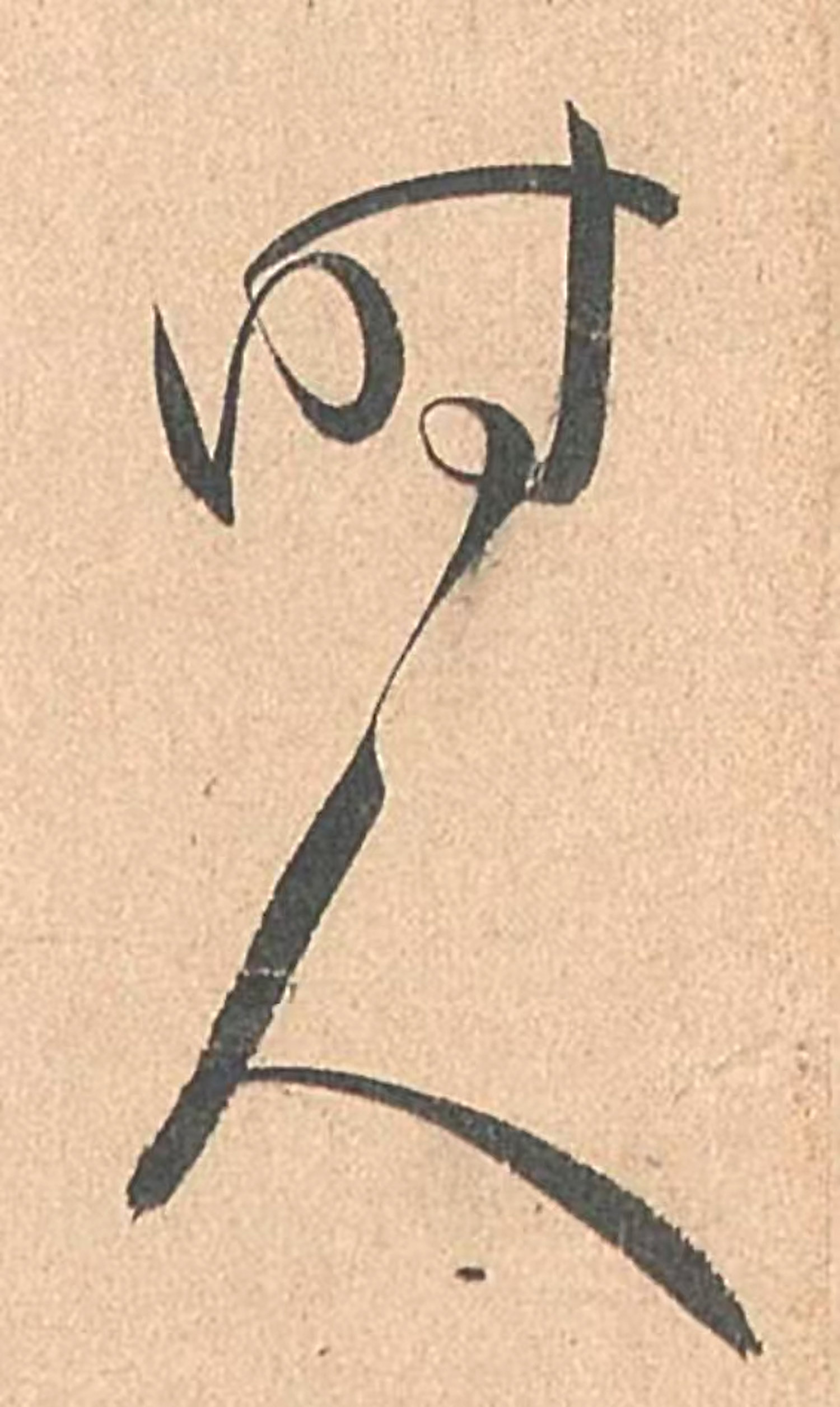

Among the more than 3,000 steles housed at the museum is a piece dating back to the Tang Dynasty (618-907) inscribed with 1,903 characters collated from a variety of Wang's works available at the time. In De Laurentis' perspective, this single stele is where the authentic charm of Wang's calligraphy lies.

All along, language barriers have largely kept foreigners from fully appreciating the beauty of Chinese calligraphy, a visual art form often compared to modern abstract painting. Even contemporary Chinese natives accustomed to using pens and typing can easily get lost in the maze of brush calligraphy.

Yet the story behind this stele, which involves three major historical names, may offer a glimpse into Wang's historical influence.

During the early Tang Dynasty, Buddhist monk Xuanzang traveled westward to Central Asia and then studied in India. Seventeen years later in 645, he brought 657 titles of Buddhist scriptures back to his homeland. Since then, in the Tang capital of Chang'an, today's Xi'an, he dedicated himself to translating the scriptures.

In the summer of 648, a year before his passing, Li Shimin, known as Emperor Taizong, wrote a preface to Xuanzang's newly completed translation after spending over a month reading more than 100 volumes. Crown prince Li Zhi recorded this process.

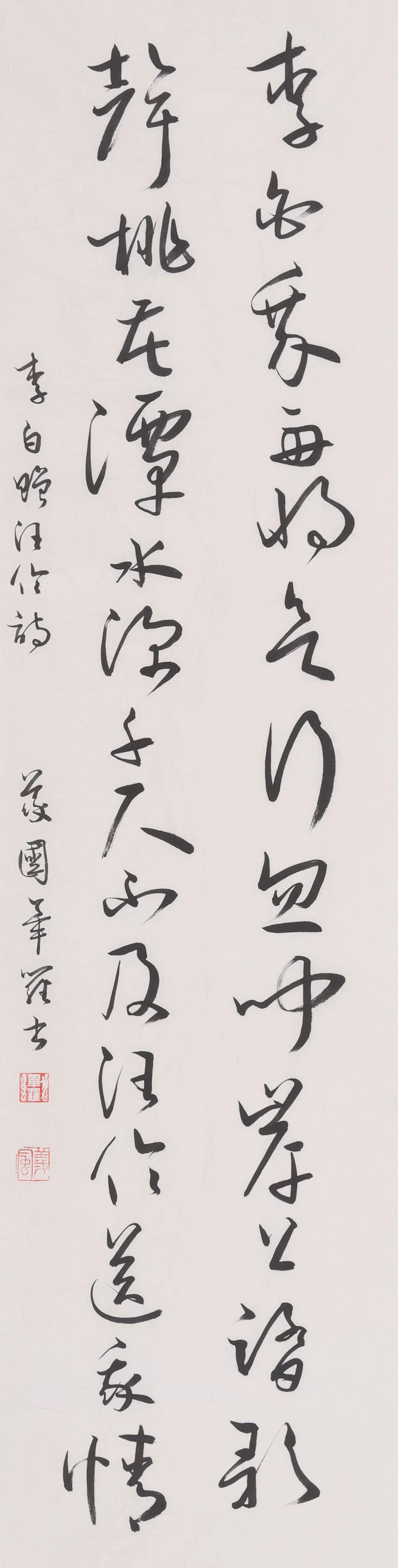

These two royal texts in honor of Xuanzang and the dharma, together with the master's translation of the Heart Sutra, were transcribed onto a monument with characters collated from more than 2,000 scrolls of Wang's calligraphy that Emperor Taizong collected, mostly written in xingshu (semi-cursive) style.

Under the supervision of monk Huairen from the capital's Hongfu Monastery, the monument was finally completed in 673 and placed at the monastery, nine years after Xuanzang's passing.

Three centuries after Wang's time, his calligraphy was showcased as a royal endorsement of the spread and adaptation of Buddhism in China. At a time when it was an extraordinary privilege to see Wang's calligraphy scrolls, this monument, standing in a public space, became a destination of pilgrimage, with copies and ink rubbings produced one after another.

"Despite its foreign origin, Chinese intellectuals admired Buddhism using Wang's calligraphy. It was only with the open-mindedness and rich imagination of the Tang Dynasty that such an idea could have possibly been conceived," says De Laurentis, who leads the Guangzhou academy's Centre for the Study of Handwriting Cultures and Artistic Exchange.

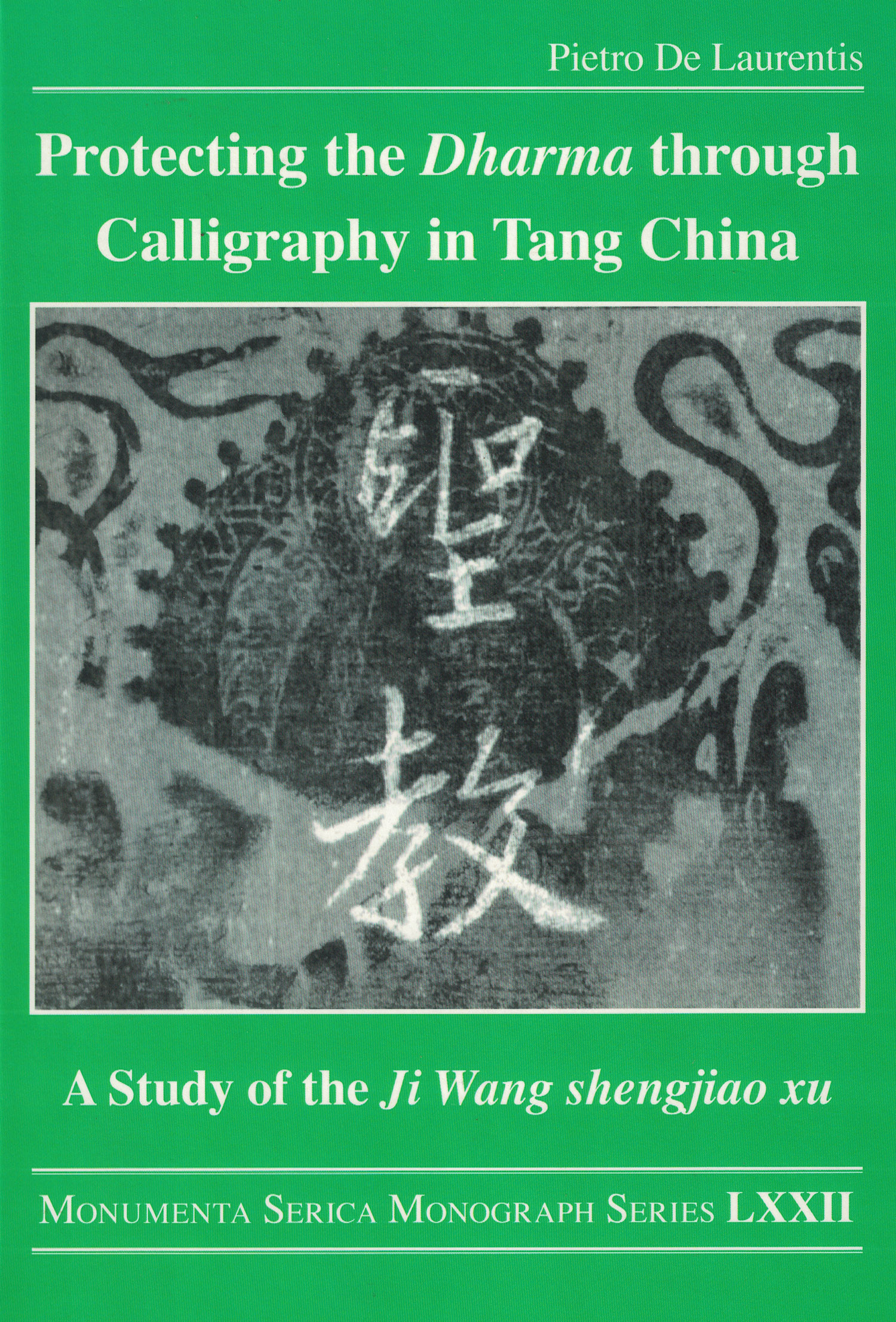

He published a monograph in English in 2021, which scrutinizes the monument's historical context and significance, as well as its artistic value.

"I would consider calligraphy a crucial aspect of the civilizational history of China and a highlight of Chinese culture, as it encompasses many aspects of the social concepts and daily lives of the ancient times."

Effortless virtuosity

During collating, Huairen prioritized resurrecting Wang's writing in its natural state, De Laurentis says.

Although the characters were selected one by one from different scrolls written at various stages of Wang's life, Huairen endeavored to present a unified writing style while keeping variations, particularly in repeated words, and paid attention to making the joints of neighboring characters look natural and coherent.

Notably, Huairen intentionally included some roughly written characters to restore Wang's daily, casual manner of writing.

De Laurentis uses the classical musical expression sprezzatura to emphasize a fundamental pursuit in calligraphy — even if a piece aims to demonstrate strong and forceful strokes, the actual writing process has to be performed in an effortless way.

Like music, calligraphy is an art of time and space.

For Chinese characters, the order of strokes is much more complicated than that of phonetic writing systems like English or Arabic. which are written simply from left to right, or vice versa.

To write a Chinese character, the movement of the brush can be up and down, left to right, or outside-in — every possible direction imaginable — not to mention the kaleidoscopic composition and proportional distribution of different components.

"The relationship between different components is like the flow of a melody: sometimes loose, sometimes tight; sometimes slow, sometimes fast. It's a process of constant fluctuation and resonance," De Laurentis says.

Playing a single note can be done in a blink, like writing a character. The continuity and interplay of each stroke counts and there can be no reversal or adjustment to the completed strokes.

Fine strokes exhaust the potential and resilience of the brush tips, much like a varied finger touch makes a single key on the same piano produce different textures of sound.

Imagine when a pianist takes a new sheet of classical music and reads the notes — sometimes conducted by a metronome — striving to reproduce exactly what the various notations on the score indicate.

Yet, when they become more familiar with the music and can interpret its voice parts, harmony and chord progression with their own subtle ingenuity, the music becomes spontaneous and embedded with the musician's identity. Learning calligraphy involves a similar process.

Therefore, interpretations and imitations of the works of great calligraphers are crucial in calligraphy, not only for perfecting the techniques but also for experiencing human emotions and wisdom and refining one's character.

No later than the Western Zhou Dynasty (c.11th century-771 BC) had the Chinese developed an emphasis on beautiful writing, according to De Laurentis.

People from various social strata cultivated aesthetics through writing while accumulating wisdom in dealing with the richness and complexity of character structures, the abundance of styles and the combination of different components.

"It reflects a person's unique way of thinking and problem-solving."

Moreover, calligraphy mirrors the mind. De Laurentis expresses his admiration for Master Hongyi (1880-1942), whose name was Li Shutong before becoming a Buddhist monk and making great achievements in painting, composition, theater, calligraphy, seal carving and poetry.

"When copying other calligraphers' works, Master Hongyi withdrew himself and wholeheartedly conformed to strokes and the temperament of others. He demonstrated compassion and universal love in his facsimiles," says De Laurentis.

Inclusive characters

To learn something different from European culture, De Laurentis went to the University of Naples "L'Orientale" — one of the oldest schools of Sinology and Oriental studies in Europe — to study Chinese in 1996. Two years later he arrived in Beijing for the first time, where the young Italian enjoyed browsing bookstalls and shopping for calligraphic reproductions, particularly drawn to the variety of fonts on shop signs and light box advertisements lining the streets.

Back in Italy in 1999, he began systematically learning calligraphy with calligrapher Wang Chengxiong from Shanghai. He has since kept the habit of regularly copying works of ancient masters, not only as a hobby but also as a research approach.

"It feels like having direct conversations with ancient literati. The subtleties in the brushwork, structure and composition are not always discernible to the eye but can be understood only through dedicated practice," says De Laurentis.

He particularly favors Tang Dynasty calligrapher Ouyang Xun, whose kaishu (regular script) works are vigorous and forceful, yet with orderly strokes, as well as rigorous and well-proportioned structures.

Starting from the history of calligraphy — handwriting is a fundamental aspect of intellectual life — De Laurentis gradually expands the scope of his research to the overall cultural temperament in ancient societies.

He has also translated 120 poems by Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai into Italian and introduced the master's life stories and spirit to his fellow countrymen based on extensive research.

The Sinologist's Chinese name Bi Luo is derived from a sentence in the Taoist classic Chuang Tzu (The Book of Zhuangzi), which emphasizes the infinity and inclusiveness of the universe, therefore suggesting that it's better to accept and adapt to changes rather than being stuck in obsessions.

De Laurentis is one of the few Sinologists specializing in Chinese calligraphy. In his observation, Western artists and scholars on textual cultures are more interested in and sensitive to the beauty of Chinese characters and the texture of brushstrokes than Sinologists.

By comparing Wang Xizhi — the most well-known calligrapher in Chinese history — to da Vinci, he hopes Westerners can immediately grasp the extent of Wang Xizhi's significance and influence in China and throughout East Asia.

"On the other hand, it's a reminder for Chinese scholars that they should treat their calligraphy traditions with the same reverence that Italians have for masters like da Vinci and Raphael."

There's no denying that Chinese people are more knowledgeable about Western arts than Westerners are about those of China. Yet, great artists would naturally become aware of other artistic traditions, he says.

In December, on academic bimonthly Contemporary Artists, De Laurentis published an essay on the historical and contemporary spread of Chinese calligraphy in the West, summarizing his 10 years of research and reflections on this topic.

He mentions that by the time renowned Chinese painter Zhang Daqian (1899-1983) visited Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) in Nice, France, in 1956, the latter had already been studying ink painting and asked Zhang technical questions.

And among the numerous merchants, diplomats and monks visiting China throughout history, "there must have been people like me who, in addition to completing their missions here, also felt connected to the culture and spirit of China", says De Laurentis. "We should not eliminate this possibility."

Zhang Jingye, a doctoral candidate at the Guangzhou academy and the Swansea College of Art at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, says that when tutoring her doctoral dissertation on the imitative tradition of calligraphy, De Laurentis attaches great importance to the sensitivity to the art of calligraphy as the foundation of her study.

ALSO READ: Wings of tradition

"The most fundamental aspect of calligraphy research is the calligraphic art itself rather than constructing the history of calligraphy from the perspective of the sociology of art or anecdotes of artists. Western studies on Chinese art history often lack the investigation of the captivating nuances of the strokes. In my case study, I've focused mainly on appreciating these subtle aspects," Zhang says.

One day last February, while she practiced calligraphy with a small brush at the British Library, a local woman observed her for a long time and was impressed by the richness of the brush movements.

"The beauty of Chinese calligraphy is not abstract. It simply takes time and patience," she says.

Lin Qi contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at fangaiqing@chinadaily.com.cn