Nezha's ancient adventures brought back to life with box office smash-hit movie, Yang Yang reports.

In Chinese literature, there might be no other characters more rebellious than the Monkey King Sun Wukong from Journey to the West and Nezha from Investiture of Gods. Both novels were written during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

With magical power, they defied the hierarchy, fighting against unjust destinies. That's why the two are so popular with Chinese people, writers, artists and, in particular, filmmakers.

Last year, China's first triple A-rated video game Black Myth: Wukong shone on the world stage. This year, it is Nezha's turn. Since Thursday, Ne Zha 2, an animated movie by director Yang Yu, better known as Jiaozi (Dumpling), the sequel to Ne Zha (2019), has been shown overseas in countries, including Australia, New Zealand and the United States, and will show in others such as Japan, Singapore and South Korea. Opening on Jan 29, the start of the Spring Festival holiday, it made Chinese box office history, with earnings surpassing 10 billion yuan ($1.37 billion) by Thursday, topping China's all-time best-selling movies list. It also makes Ne Zha 2 among the top 20 highest-grossing films in global cinematic history.

READ MORE: 'Ne Zha 2' becomes China's all-time top-grossing film, total forecast hits 10b yuan

Despite their similar determination to resist, compared to the Monkey King, the story of Nezha in Chinese mythology is more tragic in tone. His identity as the child of mortals has given people more space to adapt his story to different eras especially after the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), though its rebellious core has never changed.

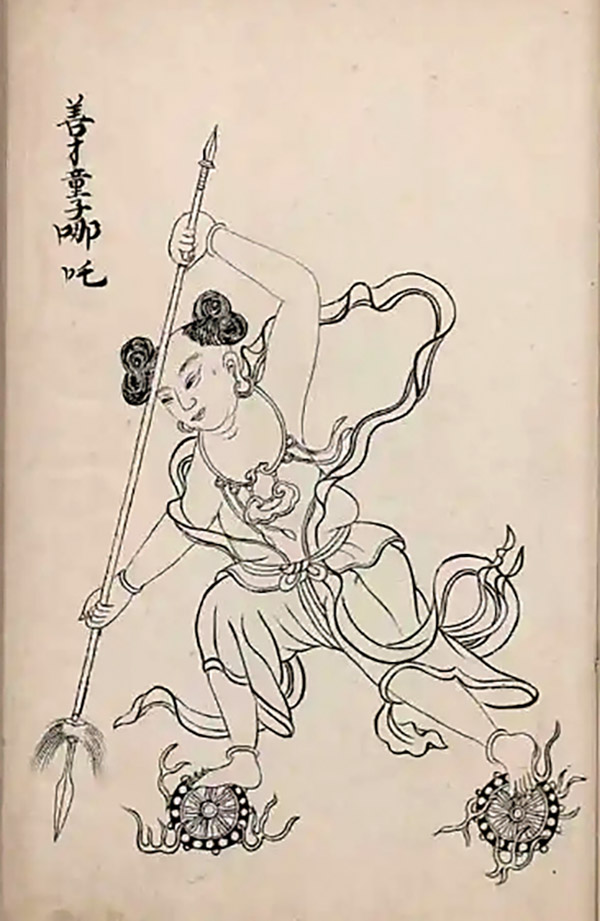

It is said that the mythology surrounding Nezha spread across China in the wake of the arrival of Buddhism. Studies of Buddhist literature from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) have found that Nezha was depicted as the third son of one of the four Heavenly Kings of Buddhism, the Guardian of the North, according to A Study on the Evolution of Nezha's Divine Image, a paper by professor Liu Wengang of Sichuan University, published in 2009 in the periodical Religious Studies. Nezha is a giant Yaksha god (a nature spirit and guardian of wealth) and Dharma protector (a spiritual entity safeguarding the teachings of the Dharma, or religious and moral law).

In Buddhist works, Nezha often appears together with his father, carrying a magical miniature pagoda. His duty is to help him guard the Dharma, ward off evil spirits, and protect people.

As Dharma protectors and Yaksha deities typically have fierce visages, symbolizing their resolution against malevolence, Nezha was often portrayed with a formidable and wrathful countenance.

Buddhist texts about Nezha's unusual relationship with his parents are missing. Researchers found in the retellings and discussions of existing early materials from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) that Nezha once dissected his own body and returned his flesh to his mother and his bones to his father.

Before the end of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), he was basically depicted as a Yaksha god with three heads, six arms and a formidable, wrathful countenance, according to Liu.

As Buddhism continued to spread, ancient China absorbed and adapted the religion, and folk beliefs evolved. Nezha's portrayal gradually departed from its Buddhist origins and took on a more distinctly Chinese character.

For Liu, the first remarkable evolution of Nezha's image occurred in the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), during which Li Jing, a strategist in the Tang Dynasty, was worshipped as the heavenly king, Nezha's father. Consequently, Nezha became the third son of Li Jing.

From a fierce Yaksha god to a Chinese deity, this change opened up space for development of Nezha's image with colorful interpretations of stories in the following centuries. Nezha has gradually become a classic literary character in China, blending elements of Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism.

Varied versions

With the emergence of important god-and-demon novels such as Journey to the West and Investiture of the Gods, the literary image and story of Nezha was standardized and became popular. In the Investiture of the Gods, he is depicted as the son of Li Jing, a general guarding the Chentang Pass, and his wife Yin Shiniang. Nezha is an adorable, slender and elegant child with magical powers, incarnated from a magical gemstone, the treasure of a Taoist immortal sect. His destiny is written in the stars — he has to die before becoming a deity.

With two magical weapons: Qiankun Quan, or the universal ring made of gold that can shrink or grow in size, and Huntian Ling, a red armillary sash that floats around his body and can be used to immobilize or strangle rivals and regenerates if torn, Nezha goes to take a bath in an estuary of the East Sea on a hot day when he is 7.

He starts playing with Huntian Ling and splashes around in the water. Instantly, the sash turns the East Sea Dragon Palace upside down. The Dragon King Ao Guang sends a Yaksha to find out what has happened. Nezha kills the Yaksha using his ring. Then Ao Guang's son Ao Bing offers to fight the child, but is also killed. Ignorant of his wrongdoings, Nezha removes Ao Bing's dragon tendon and plans to give it to his father as a belt.

To seek justice and revenge, the East Sea Dragon King unites with the dragon kings of the West, South and North seas to flood the Chentang Pass. To save the people and placate the dragon kings, Nezha dissects his body, returning his flesh to his mother and his bones to his father. Later, his mother builds a temple with a gilded statue for his soul to dwell in and be worshipped for three years before he is reborn, as his destiny requires.

However, his father, still angered by these deeds that might ruin his career, breaks the statue and burns down the temple. Nezha's mentor, a Taoist immortal Taiyi Zhenren uses lotus roots to re-create his body and resurrects him. After being reborn, Nezha wants to kill his father, who escapes narrowly several times and is given a magical pagoda by another Taoist immortal to subdue Nezha.

For hundreds of years, Nezha's stories have been adapted into countless works of art. In the above-mentioned paper, Liu writes, "gods are products of society, evolving with the times". In this case, Nezha is intertwined with the spirit of the times.

At the dawn of reforming

One of the most successful adaptations is the animated movie Nezha Conquers the Dragon King released in 1979 when China was at a turning point at the start of the reform and opening-up.

The animated film, produced by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio, was China's first large-scale, color, wide-screen feature film. It won numerous awards both domestically and internationally and has become a cherished memory for a generation. Many film critics, such as the late Zhong Dianfei, acknowledged the film as a feat, which "restructured mythical stories in the modern context, and implied the spirit of reform and innovation". The film's artistic style, including its ink-wash backgrounds and opera-inspired action design, represented a great achievement in the localization of Chinese animation.

The movie paints Nezha as a tragic and rebellious character. In the story, the four dragon kings cause chaos, putting the people at risk, while the Yaksha abducts young boys and girls. When the four dragon kings lead a massive army to flood Chentang Pass, Nezha wants to retaliate, but his father intervenes and confiscates Nezha's magical weapons. He finally sacrifices his life to save the people of Chentang Pass, also displaying his rebellion against destiny and patriarchy.

For Lu Shihan, a micro-blogger with more than 3.5 million followers on Sina Weibo, in this 1979 film, the dragon kings symbolize decaying feudal rule, while Li Jing represents a feudal family. Nezha, the revolutionary young hero, breaks away from his conservative family and disrupts the old ways of the East Sea, Lu writes in a recent post, adding that this narrative is a clear depiction of revolution, akin to the experiences of many revolutionaries of past generations.

Coming-of-age

The latest adaptation, Ne Zha 2, directed by Yang, and now a popular blockbuster, incorporates his understanding of the relationship between personal growth and the external world, and the dream to fight for fairness in a bigger context.

"Every era has its own Nezha, serving the current audience," Yang said in a previous interview, adding that "we continue Nezha's spirit of resistance, particularly seen in the struggle against fate".

In his version, Nezha is reimagined as the story of a boy with dark circles around his eyes, who breaks stereotypes, and the Dragon Prince Ao Bing as a kindhearted youngster, while the Dragon Kings and Shen Gongbao, a key villain, who is a leopard demon turned celestial being, each have their own struggles.

Good and evil no longer stand in binary opposition. The Dragon Prince Ao Bing and the Dragon Clan embody spiritual burdens stemming from ancestral responsibilities.

The old oppressive hierarchy with biases and hidden agenda seems indestructible. In Ne Zha, the audience witnesses how one person, upon learning of their cruel, predetermined fate, strives to overturn it. In its sequel, Ne Zha 2, the audience sees how millions of the oppressed fight against destiny for justice.

The portrayal of family relationships is strengthened, with improved parental personalities: The father is gentle, implicit and introverted and the mother is a brave military officer.

It also reflects the director's personal emotional projection. From a medical background, he switched to animation midway through his studies, although no one believed he could succeed.

"Without the support of my parents, I wouldn't have come this far or persevered for so long in animation," Yang said in an interview with The Beijing News. "Nezha was also able to change his fate because of his parents' acceptance, support, and love."

ALSO READ: Ne Zha collectibles catch blockbuster movie's coattails

Compared with that old image of a Buddhist or Taoist deity, this latest Nezha resembles a real human child. Beyond the story, the director hopes to offer more encouragement, hope, warmth and strength to those pursuing their dreams, those running forward, he said in an interview with Southern Weekend.

Yang Chenxi, a 17-year-old senior middle school student from Huzhou, Zhejiang province, resonated with the spirit of the movie. She watched Nezha five times and Nezha 2 once during the Spring Festival holiday.

"There might be a similarity between Nezha and me. We both care how other people see us," she says. "This version of Nezha is different from the typical storyline of a divine being reincarnated to save others and himself. Instead, it begins with Nezha as an underestimated demon who gradually proves himself, defying fate to start anew. Along the way, he and the Dragon Prince Ao Bing become friends. Despite his status, Ao Bing faces similar doubts.

"Their intertwined journey features fresh plot twists, thought-provoking dialogue, and inspiring moments, making it both uplifting and touching," she adds.

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn