Peng Wei uses images of the past to paint a picture of today, Lin Qi reports.

Peng Wei is one of those artists who do not speak a lot. When the ink painter sits down for a talk, the range of her interests contributes greatly to the quality of time spent, and is a pleasure, both for herself and for her listeners.

For example, during a recent podcast series, Peng took listeners on a thought-provoking journey through the past and the present, the East and the West, crossing the boundaries of history, culture, society, and technology.

She talked about the life and work of Marguerite Duras (the French author of The Lover) and the music of Mozart — Queen of the Night aria from The Magic Flute being one of her favorites — before delving into the developments of the digital world, which she says human greed has overblown.

She also talked about how talented she feels Italian author Elena Ferrante is to be able to create so many interesting characters, no matter how minor, in her best-known work, the Neapolitan Quartet. Peng said she envies Ferrante's ability to hide away from the world — the writer's name is a pseudonym, and little is known about her.

READ MORE: Art crosses boundaries to exciting era

The podcast, Speaking of the Snake, has invited a string of Chinese celebrities and artists to explore the symbolism of the snake. The series was launched by Prada and is part of the brand's exclusive Year of the Snake campaign, for which it also produced a capsule collection. Titled We, the Snake, the campaign reimagines the snake's serpentine coils as a powerful symbol of community and togetherness.

"I like the snake very much. I like the simplicity of its slender body, and its scales look refined. Snakes have many colors," Peng says. "They are quite beautiful. I say this from an aesthetic point of view."

She once touched a snake. "It felt smooth. I thought about having one in college, because it sounded pretty cool. That is also how I feel about the snake. It is a cool animal."

She adds, "The snake is a complicated creature in both Asian and European mythologies. It is a symbol of good things and also of evil things. I think the mixed imagery of snakes makes them unique and attractive."

She speaks about the White Snake and the Green Snake, the snake spirit-turned human protagonists of Bai She Zhuan, The Legend of the White Snake, the folk tale about a romance between the White Snake and the scholar Xu Xian.

"The two spirits are loved because they are true in temperament, courageous and compassionate. They dare to sacrifice for love, and for others. They are lovely women. One can also find similar female characters in Liaozhai Zhiyi (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio).

"But I also have a mixed feeling when reading the stories. They were written by men, and reflect their notions of an ideal woman, one who is willing to sacrifice herself for the one she loves."

The snake and its symbolism make an excellent entry to Peng's paintings, in which she appropriates the formats, recurring motifs, and figures of classic Chinese paintings, myths and fairy tales, and texts, to tell their stories in different contexts.

She has constructed scenes, half real and half imagined, in which she narrates the stories of men and women, revealing their emotions and thoughts.

Through smooth layering and the shading of pale colors, she gently ushers the audience into a painterly world at a calm pace, in the same soft way she speaks.

Although dressed in ancient clothing, the happiness, sorrow, anger and perplexity of her figures lead people to think of similar, modern situations.

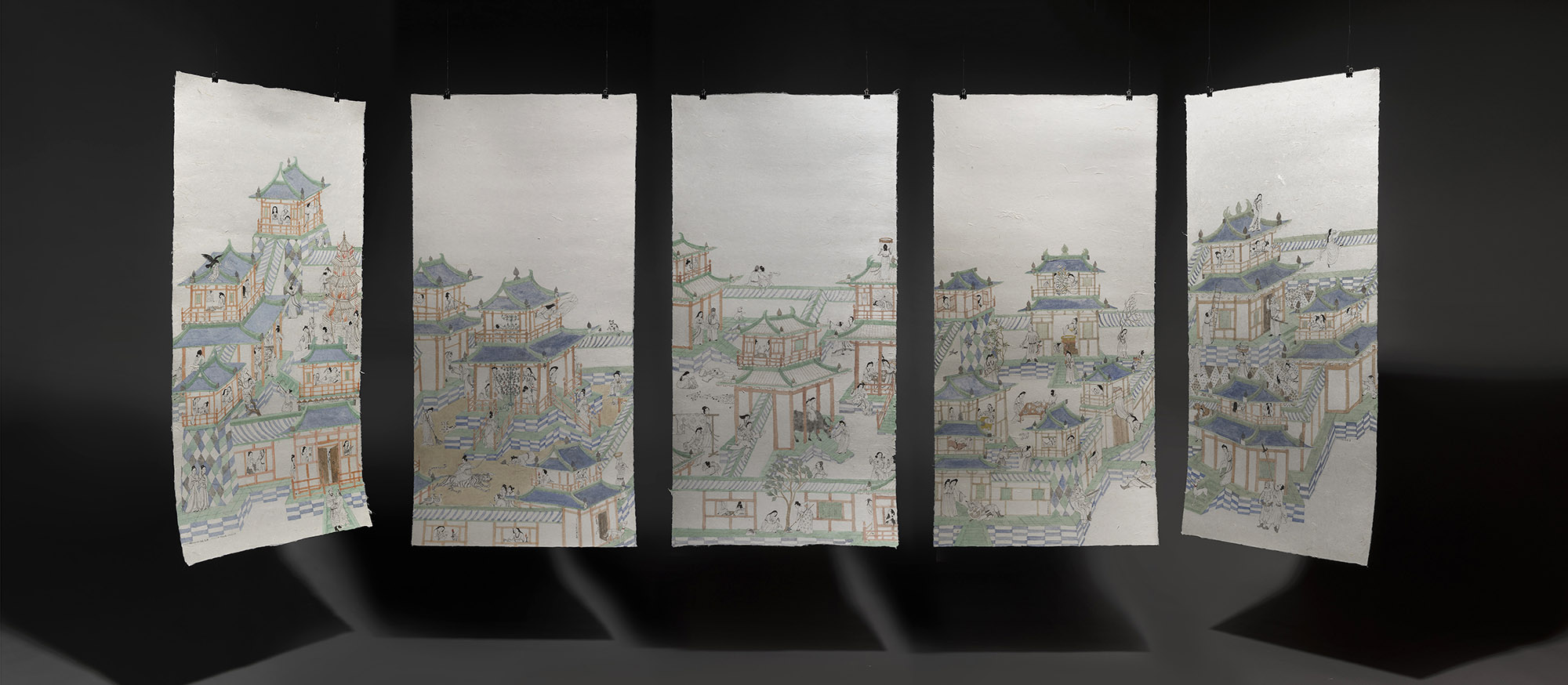

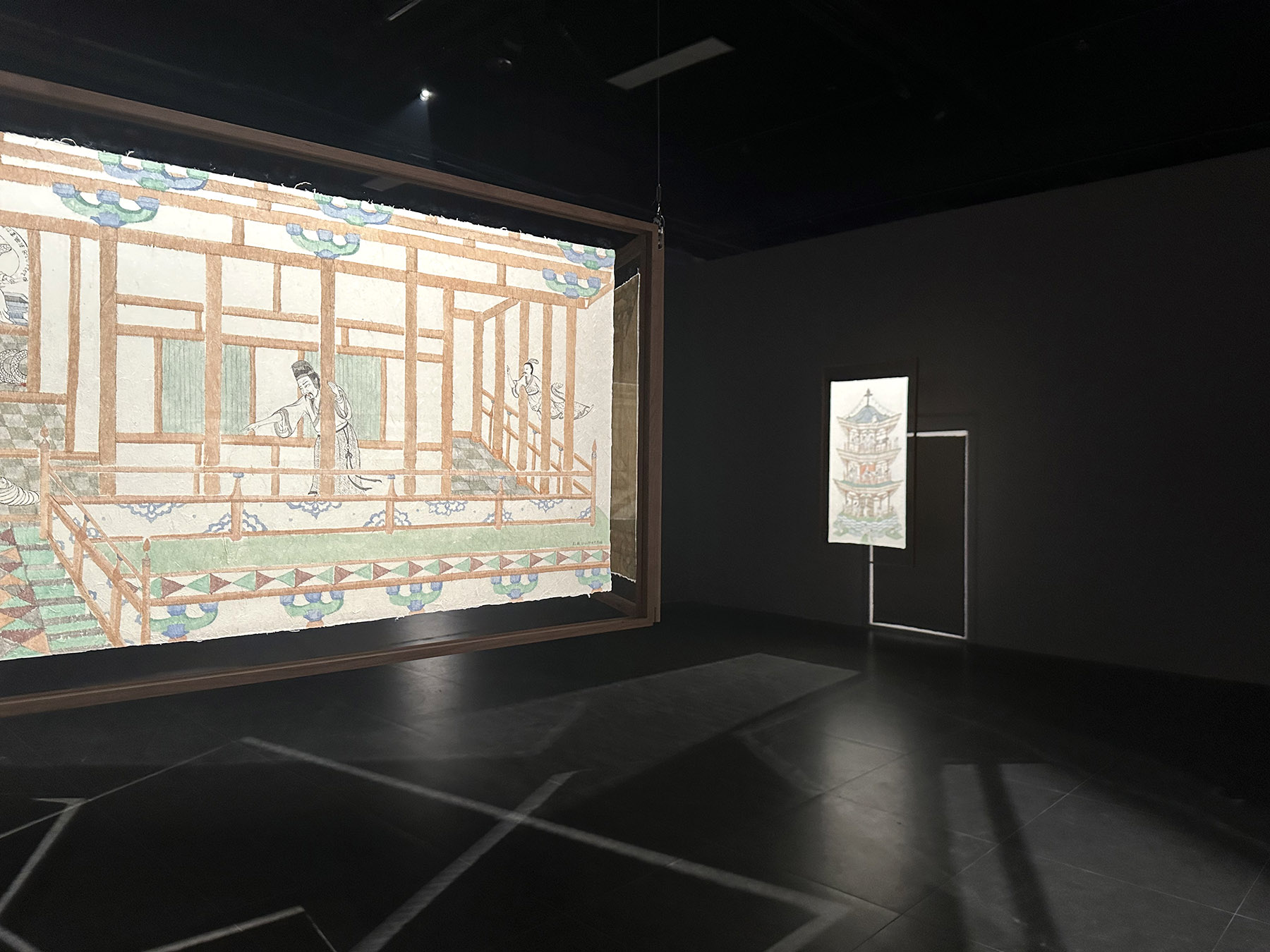

"In her paintings, stories take place everywhere: by a window, in a corridor, on the top of a roof, in courtyard, a pavilion, a tower," says Cui Cancan, curator of Peng's solo exhibition currently on at the Changsha Museum of Art in Changsha, Hunan province. "In these stories, she is building a city for women, with a totally new social order." The show, Seven Days, runs until March 30.

Peng says she used to reject the narrative method in her work.

"I believed that as long as I had impeccable technique, I could paint whatever I wanted. I believed that technique would stand the test of time, and I didn't need to entice the audience to my work by telling stories, that people would be attracted to my paintings," she says.

Her transformation took place around 2017, when new experiences and changes to her life motivated her to share.

"I had experiences that were complicated and that raised questions, which I found difficult to answer in a simple, straightforward way."

The narrative details she saw in murals in Dunhuang, Gansu province, and frescos in Italy also opened up her mind to the power of narrative paintings.

"A good painting is like a literary masterpiece, a fine, hand-knit rug in a variety of sophisticated patterns," she says.

"It is like when you read Dream of the Red Chamber, for example. No matter which chapter you begin with, or through whatever perspective you look at it, it is a brilliant piece every time."

ALSO READ: Art show displays creative exchange

Peng says that good narration shows that the truth is complicated, and that to tell the truth, the whole truth, is a complex process.

In her paintings, that complication is vividly presented in one room after another, one level of a tower after another, through rich detailing that peels apart the multiple facets of human nature, like the layers of an onion.

Cui says that part of the charm of Peng's narrative paintings is her use of liubai (leaving blankness), a traditional method in classical Chinese painting, where emptiness is employed to prompt viewers to think about the implied meaning and the future development of the story in them.

Asked why she paints ancient figures, rather than contemporary ones, Peng says it is a way for her to remain detached from the world, so that she can observe it calmly.

She senses a similar detachment in Ferrante, who Peng says imbues her characters with human interest but from a distance.

Peng adds that, while she paints the worlds of men and women, she seeks to show the influence of the past and of what is happening today, on human nature, and that together, these individual stories paint an epic picture of society.

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn