Alarm bells about potential existential threats to movie theaters — stemming from streaming access and shifting audience demographics — continue to ring. Recently, a similar threat has been directed at film festivals. Though the roles they play are changing, film festivals remain the first and best source of discovering new talent and ideas. Traditionally many of those new talents have made their debut with short films. Generally more focused due to the time limit and able to present a broader spectrum of themes and realities compared to a feature-length film, short films are festival underdogs and very often among any edition’s best offerings.

“We get over 3,000 submissions every year, and a large chunk of them are short films,” begins Geoffrey Wong, director of programming at the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society. “Perhaps it’s because of social media and all those platforms or the iPhone, but all this has made it easy for everyone to make their own films. And shorts are something to begin with.” Despite the precarious status of Fresh Wave — Hong Kong’s short-film incubator festival — Wong claims to have seen a boost in both production and audience interest in shorts in the last few years.

READ MORE: Pictures of diversity

“I think the film industry is changing. Many directors are asking, ‘Do I need to make a film that’s 80, 90 or 180 minutes?’ It’s not about long and short anymore, and I think the presentation of short films at festivals will become more important in the coming years,” Wong argues, noting that David Cronenberg, Pedro Almodóvar, Wes Anderson and Tsai Ming-liang are among the global directing titans who have been dabbling in short-format filmmaking.

Leos Carax’s new film, It’s Not Me, screens with La chimera director Alice Rohrwacher’s latest, An Urban Allegory — with a combined running time of 63 minutes. “I genuinely think directors enjoy making shorts because it gives them a certain amount of freedom. They don’t have to consider a market and box office, you don’t need a theatrical release or festivals,” says HKIFFS curator Alvin Tse. “They can do things their own way, and experiment with ideas that may have been percolating for many years.”

The 49th HKIFF is presenting upwards of 40 short films — when the Avant Garde Shorts, World Animation, and new, nonfeature-length work by Juho Kuosmanen (Silent Trilogy) and Michel Gondry (Maya, Give Me a Title), among others, are factored in. The Short Film Competition this year comprises 18 documentary and narrative films from around the world spanning three programs that, intentional or not, connect to each other effortlessly.

“We don’t set an agenda or topic before choosing a film. We look at what the films are about, what the quality of a film is, what we can actually present — and then we might be able to find a through line. That’s the case for all programs,” Wong says.

The titles include Arshia Shakiba’s Who Loves the Sun (Canada), which documents life at Syria’s stopgap oil refineries. It was awarded best short at Venice Film Festival 2024. Yoriko Mizushiri’s Ordinary Life (Japan/France), a prize winner at the 75th Berlin International Film Festival in February, is a delicate, pastel-hued portrait of the day-to-day that defies definition. Wu Lang’s Here Comes the Sun (China) is about a leafy seaside town where life is disrupted by the progress of a rocket launch. Cem Demirer’s creatively textured psychological thriller Absent (Turkiye) is about an amusement park worker wrestling with his mental health issues. The list also includes My Therapist Said, I am Full of Sadness (Indonesia) by Monica Vanesa Tedja, in which the queer artist tries to reconcile their authentic life in Berlin with their fundamentalist home in Jakarta. If there’s a unifying theme to the programs this year, it might be our collective and ongoing meditations on identity, isolation and how those are navigated in a polarizing world.

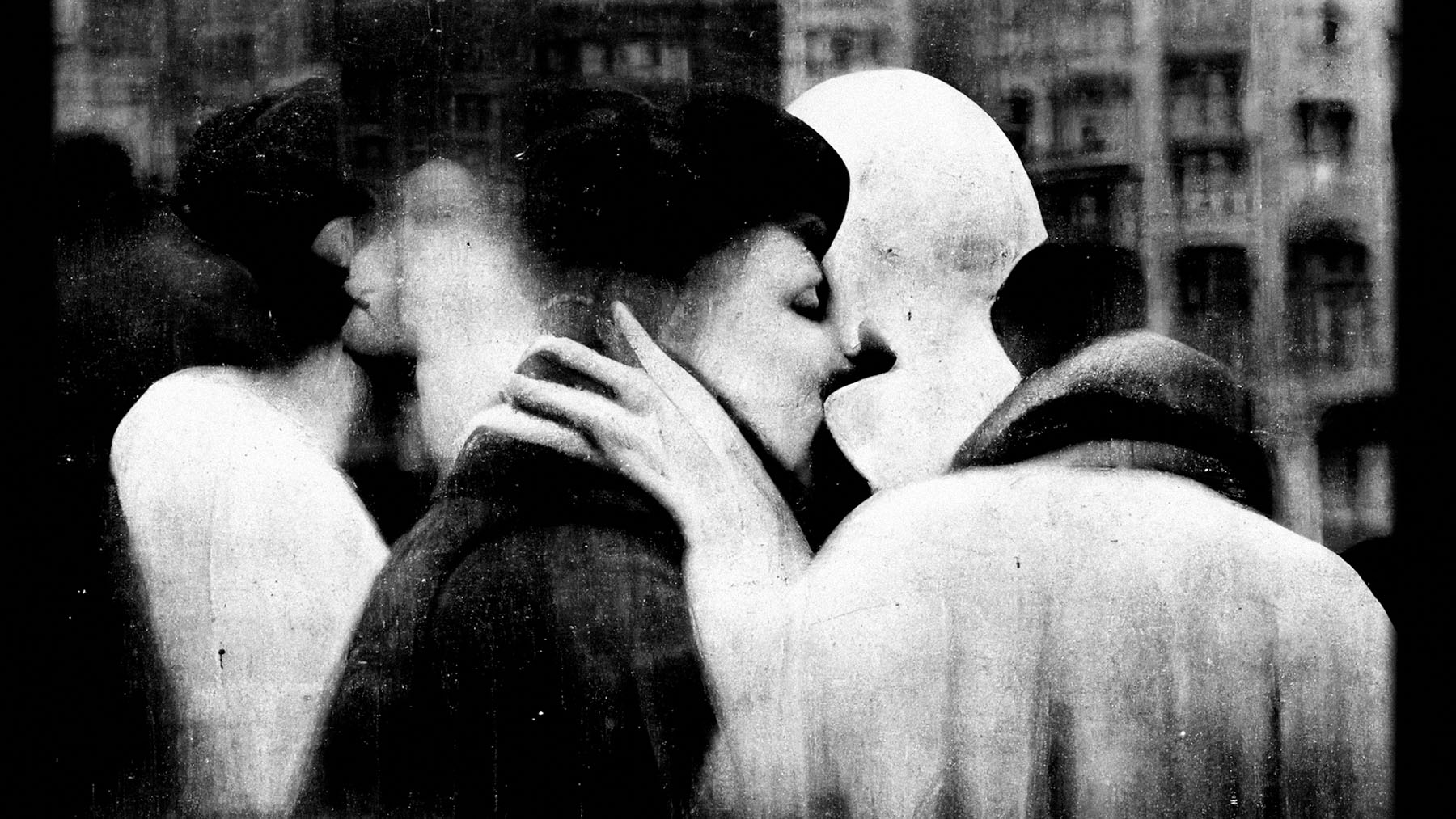

Standing tall within a strong lineup is Short Palme d’Or winner at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival, The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent (Croatia) by Nebojša Slijepčević, which quietly condemns the insidiousness of silent complicity, based on the 1993 massacre of 24 Muslims by a Serbian militia. Equally notable is Andrea Gatopoulos’ science-fiction-tinged The Eggregores’ Theory (Italy). The film’s otherworldly black-and-white images recounting the story of a mysterious plague that sweeps the globe and leads to paranoia and division were created with generative artificial intelligence that is still unrefined enough to lend the film its haunting quality and acute commentary.

ALSO READ: Animated delights

“We’ve seen quite a number of AI films, some that are quite competent,” Wong says diplomatically. “But I think when you put them together with all the other short films, live action or animation, you see there’s still something missing. This is one we’re including as a kind of experiment to see how the audience or even the jury feels about watching an AI film.”

He adds that we, the audience, are living in “a transitional period”, and that The Eggregores’ Theory “is a product of this time”.