Hakka bamboo artisan carves space for ancient art in modern life, Yang Feiyue reports.

The slender bamboo panel almost seems to breathe under the ingenious ministrations of Guo Yingxiong's knife.

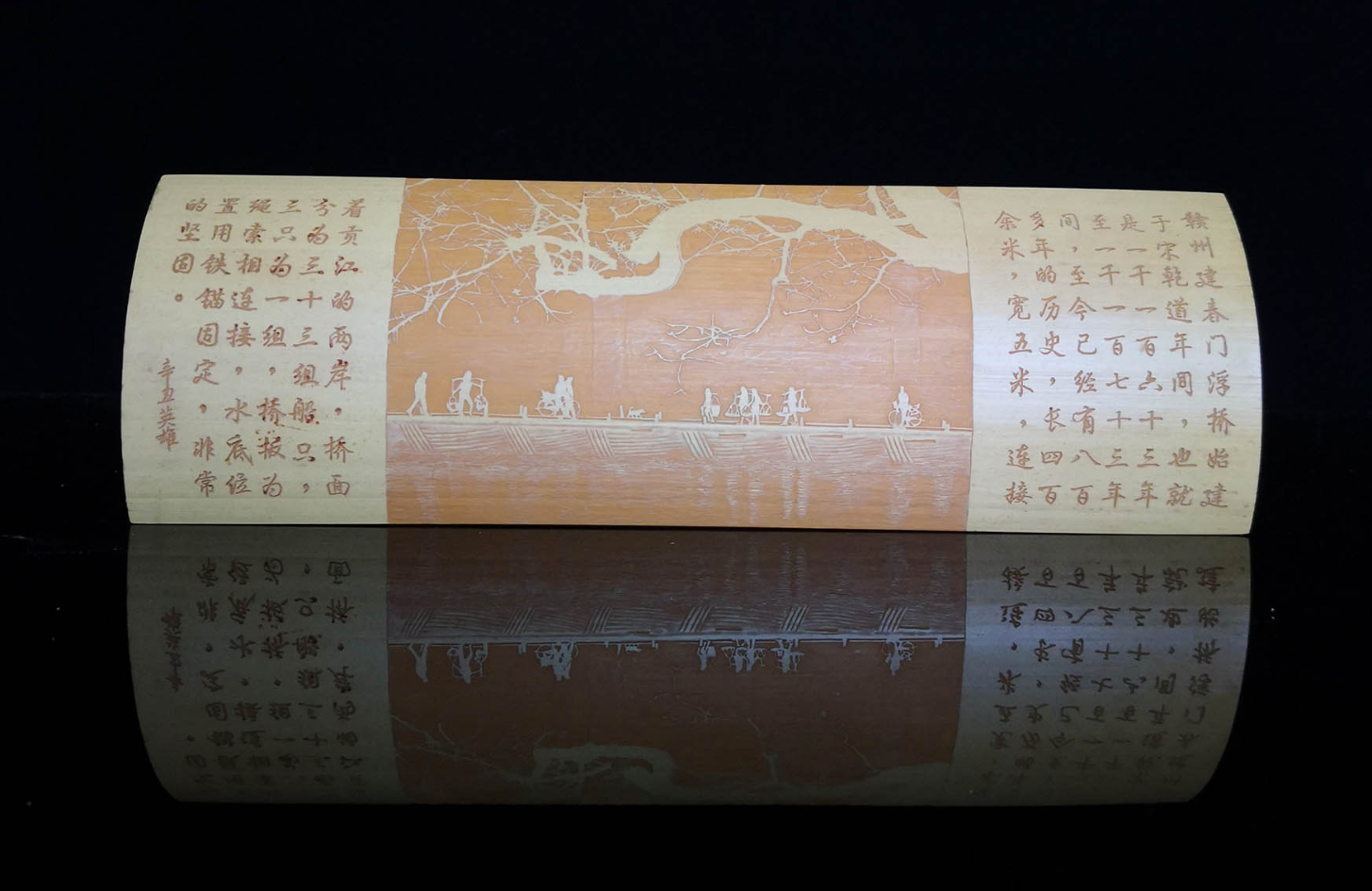

In his workshop in the Zhanggong district of Ganzhou, Jiangxi province, the 58-year-old conjures worlds that erase time, in which rivers flow eternally, the current rendered so delicately that it almost shimmers with actual movement. An ancient bridge arches over the river, carrying the rhythms of daily life unfolding on a bamboo sheet — a tea peddler's weathered face glistens as he adjusts his shoulder pole, an elderly man navigates wooden planks on his bicycle, and young lovers sit entwined on the bridge's edge, their silhouettes backlit by the sun that stains the river the color of molten copper.

Peering closer at this miniature world, you will notice the gnarled roots of a banyan tree clutching the riverbank, and the bridge's lineage traced in vermilion calligraphy.

"I try to let the material speak for itself," Guo says.

READ MORE: Artist displays pride in culture

And so the natural russet streaks of bamboo skin are shaped into sunset clouds, a knothole becomes the moon reflected in the river, while the fibrous texture is used to mimic both the bridge's wood grain, and the water's rippling surface.

For more than four decades, Guo has been a living bridge between the ancient art of Hakka bamboo carving and the modern world. His hands, ridged with calluses and scored by decades of nicks, tell the story of an art form that once graced the studies of Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) scholars.

Bamboo carving turns the humble material into exquisite canvases of cultural expression, with artisans wielding their knives like painters' brushes to create intricate, decorative patterns.

While its origins date back to the Six Dynasties (222-589) period, the art began to flourish during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), before achieving its golden age during the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

For centuries, literati revered bamboo as the living embodiment of moral integrity and spiritual purity — its unyielding straightness symbolizing upright character, its hollow stems representing humility, and its evergreen resilience signifying enduring virtue.

This cultural symbolism permeated classical poetry and literature, most famously expressed by the literary giant of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) Su Shi, who once wrote that he would "rather dine without meat than dwell without bamboo".

This history gave rise to several regional schools of bamboo carving, each with its own distinctive character, ranging from deeply layered reliefs and shallow elegant carvings, to precise calligraphy and delicate openwork.

The traditions illustrate the remarkable versatility of bamboo as a medium, from simple incised lines to breathtaking three-dimensional sculptures that seem to defy the material's natural limitations, Guo explains.

Among them, the Hakka bamboo carving practiced in Zhanggong district stands out as particularly vibrant.

Recognized in 2010 as a provincial-level intangible cultural heritage in Jiangxi, it formed as local artisans employed an approach that blends traditional calligraphic carving with creative improvisation.

The resulting pieces, from scholarly brush pots and elegant incense burners, to decorative plaques embellished with couplets, demonstrate a masterful balance between form and function.

Some pieces captivate with their minimalist purity, while others dazzle with their intricate, patternrich compositions.

Guo has been exposed to the art since childhood, as he was born to a family of displaced craftsmen from Guangdong province who settled in Jiangxi's bamboo-rich hills.

His father was skilled in multiple fields — as herbalist, carpenter, and master of root carving — and maintained the Hakka tradition of training children through rigorous apprenticeship.

"My first lessons came through pain," Guo recalls with a wry smile.

When he was 6, he was tasked with fetching his father's tools.

"He'd call for a certain knife for specific patterns, and I had to guess which one he meant," he continues.

Wrong guesses earned him slaps on the wrist, an "effective" teaching method he said that helped imprint the names and uses of dozens of specialized blades onto his memory.

This stringent pedagogy extended to preparing materials, with young Guo soon learning that true mastery begins long before the carving starts. "Bamboo selection follows strict rules, and uses only winter-cut Moso bamboo from south-facing slopes that is at least four years old to ensure the correct density," he explains.

He says that the curing process is exacting — boiling the bamboo in herbal solutions for hours to prevent insect damage, then sun-drying it until the material turns a deep amber. There are some 50-odd steps that need to be taken before the bamboo is ready to be carved.

As he made inroads into the art, Guo gradually mastered the full spectrum of sculpting techniques, establishing himself as a pioneer in preserving and advancing Jiangxi's carving heritage.

In 2021, he was named a provincial-level inheritor. He is known for the diversity of his subjects, including mist-shrouded mountain ranges, delicate bird portraits with feathers rendered through microscopic incisions, architectural wonders, and calligraphic masterpieces.

Recognition has since followed.

One of his pieces, a representation of heyu (lotus fish) measuring a mere 20 by 8 centimeters in size, masterfully incorporates 15 lively carp swimming among lotus leaves and blossoms on the inner wall of the bamboo.

In 2016, a number of his liuqing (reserved green) pieces, made using technique in which the natural gradation of the bamboo's outer skin is preserved, were purchased by museums in Jiangxi.

In 2017, Guo opened a Hakka bamboo carving workshop, the first of its kind in Ganzhou, where he has since been busy creating custom-made carved bamboo, and teaching students in an effort to pass the tradition down in this ever-changing world.

He organizes regular workshops, attracting visitors of various ages, from curious 6-year-olds to doctoral candidates, who wish to learn the intricate techniques.

He has trained 30 apprentices, two of whom have already earned the title of district-level inheritors.

Han Lu, a teacher at the Jiangxi Environmental Engineering Vocational College, became an aficionado of the bamboo art as the result of a public benefit program in Ganzhou that offers affordable cultural courses to citizens.

"When I saw that Guo Yingxiong was teaching, I immediately signed up. There's something magical about this art form — its ability to calm the mind and inculcate patience," says Han.

"Working on bamboo slices less than 3 millimeters thick, when every stroke must be precisely controlled, becomes almost meditative," the man in his 30s adds.

After completing 15 sessions, he attempted his first major project with Guo last summer, carving seven hours a day for a week.

"Guo's guidance was invaluable, particularly in material selection. Few realize the complexity that each slice requires — generations of knowledge — to be properly prepared," he says.

He has now started a research project tracing the historical roots of Hakka bamboo carving, while exploring sustainable inheritance at college.

"As a relative beginner myself, I'm determined to continue while helping others appreciate its value," Han says.

ALSO READ: Chinese Hakka food culture shines in Singapore

Speaking about his plans, Guo says he will continue to explore new creations as part of his mission to keep the art form relevant.

"While remaining rooted in tradition, we have created smaller, more affordable pieces like bookmarks and pendants to appeal to younger and casual buyers," he says.

He has also experimented with contemporary designs, blending classic liuqing techniques with modern aesthetics to attract social media-savvy travelers.

"My mission isn't just to preserve — it's to make bamboo carving vital in modern life," he says.

"Every student who learns, every tourist who buys a piece, helps this art survive."

Looking ahead, Guo plans to push for the tradition's inclusion in national vocational competitions. Through such efforts, he hopes to secure a brighter future for the art, one stroke of the knife at a time.

Contact the writer at yangfeiyue@chinadaily.com.cn