Traditional Chinese knots are aesthetic symbols with deep, philosophical underpinnings. While continuing to surprise historians, this ancient art form is also inspiring contemporary fashion and jewelry designers. Qin Wang reports.

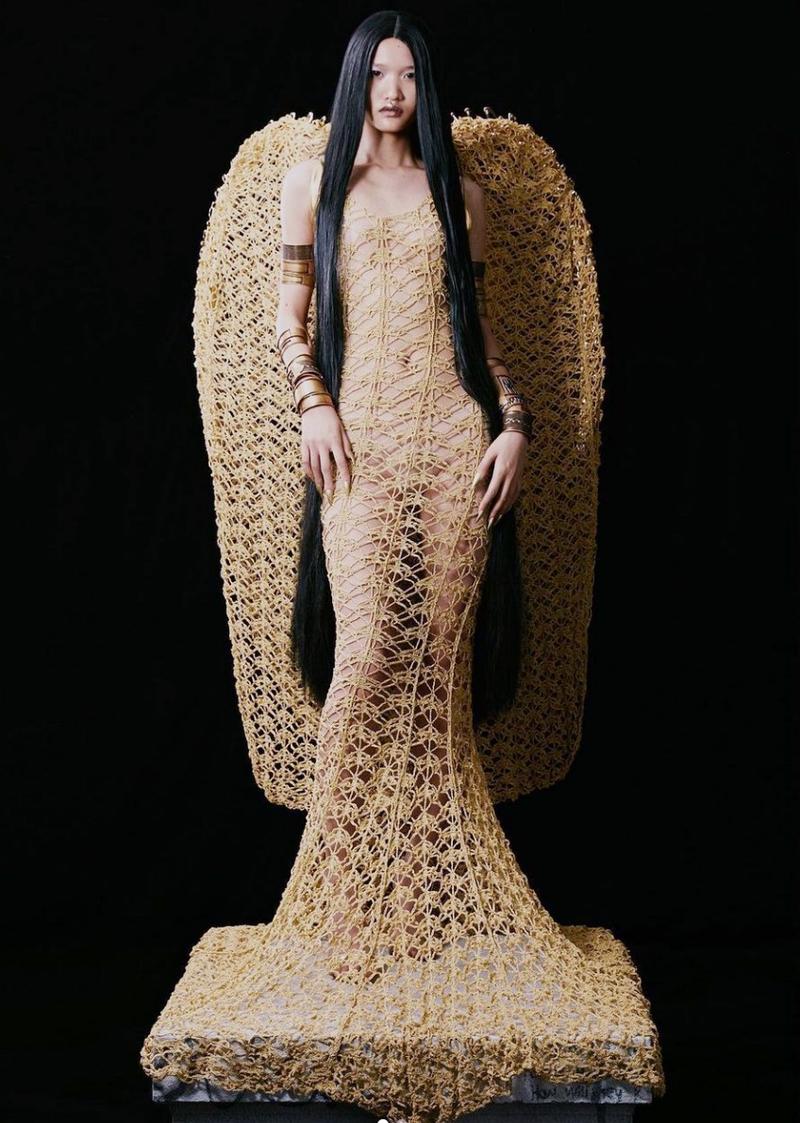

Part of its Spring/Summer 2023 collection, Chinese haute couture brand Marrknull’s crocheted, gold fishtail dress marries the avant-garde with the ancient. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Part of its Spring/Summer 2023 collection, Chinese haute couture brand Marrknull’s crocheted, gold fishtail dress marries the avant-garde with the ancient. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In 2021, Cao Haimei, an associate professor at the College of Art and Design at the Beijing University of Technology, was looking through artifacts at the China National Silk Museum when she stumbled on an incense bag from the Liao Dynasty (916-1125), embellished with plafond knots — a kind of traditional Chinese knot. According to the leading tome on traditional Chinese knots, by Taiwan scholar Chen Xiasheng, the first appearance of a plafond knot had been traced to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Cao’s chance discovery in the museum meant the knot had actually existed at least 500 years earlier.

Traditional knot-stitching is even older, dating back to at least 400 BC. Yet the technique continues to find new forms. Earlier this year, Tim Shi and Mark Wang, the 20-something designers behind Chinese fashion label Marrknull, were delighted to be among the semifinalists for the coveted LVMH Prize. One of the most daring pieces in Marrknull’s Spring/Summer 2023 collection: a gold fishtail dress whose racy silhouette belies the centuries of tradition behind its crocheted form.

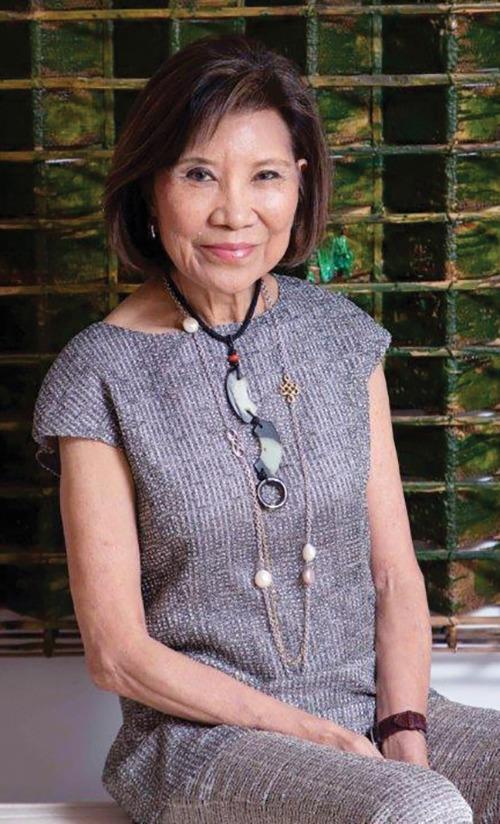

Here in Hong Kong, Kai-Yin Lo — a noted jewelry and ceramics designer as well as a cultural historian — is inspired by traditional Chinese knots in the creation of her contemporary designs. She says that while purely Chinese motifs are less likely to resonate with her Western clients, “the knot motif is a symbol that everyone can understand”.

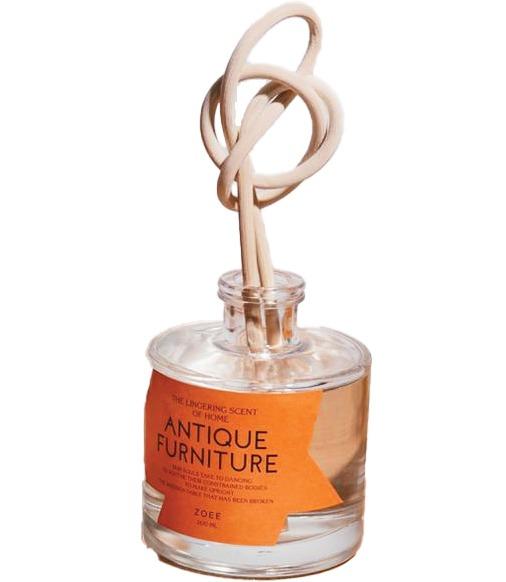

Meanwhile, young local artist Zoe Siu has also been inspired to take on the traditional form — and is assuming a free-spirited approach to its interpretation.

Cao Haimei discovered this incense bag with plafond knots, dating from an era that showed the type of knot was at least five centuries older than previously thought. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Cao Haimei discovered this incense bag with plafond knots, dating from an era that showed the type of knot was at least five centuries older than previously thought. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

What’s in a knot?

At its most basic, a knot is two ends of string or rope tied together. The forms of traditional Chinese knots range from simple ones like the double-coin knot, resembling two ancient coins intertwined, to complicated exemplars like the constellation knot, which sees smaller knots leading to a series of loops. Inspired by decorations on temple ceilings, the plafond knot has a spiraling center within a rectangular border. The most famous and difficult type is the panchang knot — also known as the eternal knot or infinity knot — according to Cheung Po-yin, a local knot-crafter with over 40 years’ experience.

To create this complex knot, two ends of one thread are woven together vertically, then horizontally. The resulting overlapping lattices are then joined to make a complete panchang knot. Pulling the lattices apart reveals a three-dimensional structure, Cheung says.

Kai-Yin Lo — cultural historian, and jewelry and ceramics designer — has noted fascinating correspondences between cultures when it comes to knot motifs. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Kai-Yin Lo — cultural historian, and jewelry and ceramics designer — has noted fascinating correspondences between cultures when it comes to knot motifs. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Playing with the normally fixed geometries involved in traditional Chinese knotting, Zoe Siu has created modified knot designs inspired by young plants such as seedlings and tree buds. For her perfume series, The Lingering Scent of Home, Siu used the double-coin knot as the basis for rattan shapes used to disperse the fragrance. Natural rattan has limited pliability, and needs to be softened with steam before it can be curved into the desired shape. “You need to bend it at just the right temperature or it will break,” explains Siu.

For her Rope Fossil ceramic series, Siu imagined how it would be if knotted ropes became fossils. Firing and soaking the twisted porcelain resulted in many mishaps, but Siu says she loves the imperfections and randomness in the handmade pieces. Next she combined the cracked pieces with actual thread to create a new series, Imperfect Knot.

“I was in the fashion industry before, and I was tired of sitting in front of a computer every day,” says the designer. “I wanted to do something humane, so I dived into knots.

“People today forget the power of our hands. Nobody will sew their clothes if they’re torn. But as survival knots show us, if you’re in danger in the wild, machines cannot save you if you don’t use your hands. So I went back to making knots with my hands.”

Kai-Yin Lo’s jewelry designs incorporate both new and old motifs, reflecting discoveries on her travels. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Kai-Yin Lo’s jewelry designs incorporate both new and old motifs, reflecting discoveries on her travels. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Eras intertwined

Kai-Yin Lo has been inspired over the years to create knots from different materials. Back in the mid-1980s, the designer was amazed to see biscuits from the Tang Dynasty (618-907), made in the shape of knots, unearthed in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. The extremely dry, desert climate of northwestern China had enabled the biscuits to remain perfectly preserved. Lo saw that the dough — made from finely ground flour — had been pliable enough to mold into knots and flowers.

Hard materials require entirely different methods of craftsmanship and are much more durable. Lo has designed knots in jade, amber, ivory and even crystal — the latter being the hardest material but also the most breakable. Drawing inspiration from an 18th century Chinese crystal eternity knot, Lo commissioned artisans in the mid-’80s to carve something similar. “Very difficult: There was a lot of breakage,” she recalls. “I think one out of seven was OK; the others would break.”

At the other end of the spectrum, there are knots that are purely functional, having nothing to do with art, aesthetics or whimsical approaches to materiality. So it is perhaps surprising to find that even the forms of certain sailing knots overlap with those of traditional Chinese knots.

Zoe Siu relinquished her office job to focus on handcrafting knots and works inspired by them. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Zoe Siu relinquished her office job to focus on handcrafting knots and works inspired by them. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

As simple as they come, an overhand sailing knot is made by forming a loop and passing the other end of the rope through the loop. The same shape, known as a single knot in China, appears on a roughly 2,000-year-old stone carving depicting the mythological deities Fuxi and Nuwa. In it, the tails of two birds intersect to form the knot.

“Originating in the Age of Discovery, sailing knots are used to fasten ropes together or onto other objects. Chinese knots, on the other hand, are symbolic,” notes Cao, the researcher who discovered the surprisingly ancient plafond knot. “Chinese knots have more figurative connotations.”

For centuries, knot designs traveled between the Eastern and Western hemispheres, along the Silk Road. During a 2008 visit to the Middle East, Lo was surprised to discover eternal knot patterns — considered a Buddhist or Chinese symbol — on ceiling beams in the eighth-century Umayyad Mosque in the Syrian capital of Damascus. She also found multitudes of round brocade knots on stone carvings and tiles in Iranian mosques — something she describes as “a wonderful discovery”.

Zoe Siu used the double-coin knot as the basis for rattan shapes used to disperse fragrance in a series called The Lingering Scent of Home. GBA briefs

(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Zoe Siu used the double-coin knot as the basis for rattan shapes used to disperse fragrance in a series called The Lingering Scent of Home. GBA briefs

(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Intriguingly, the very knot designs found in the Middle East also appeared on Chinese antiques during a similar period in history. For example, a round brocade knot can be found on a horse’s bridle on a silver pot from the eighth-century Tang Dynasty, at a time when China had interactions with West Asian and European cultures via the Silk Road.

The eternal knot is one of eight auspicious symbols in Buddhism, the religion flourishing in China from the Sui Dynasty (581-618) to the Tang, influencing Chinese architects and artistic design. Interpretations of the knot’s form vary. In Buddhism, it can be seen to symbolize entwined snakes, which since they shed their skin, represent the endless cycle of suffering, death and rebirth. A more positive reading sees the knot as a net salvaging pearls of wisdom from the sea of life.

A knot reflects many facets of the world: geometrical principles underpin its structure; communication between past civilizations can be seen in the dissemination of a motif; artistic experiments around shapes and materials are endless. The language of knots may be ancient, but it is also timeless.