How decades of research led to the rediscovery of one of the greatest gardens in Chinese history, Yang Yang reports.

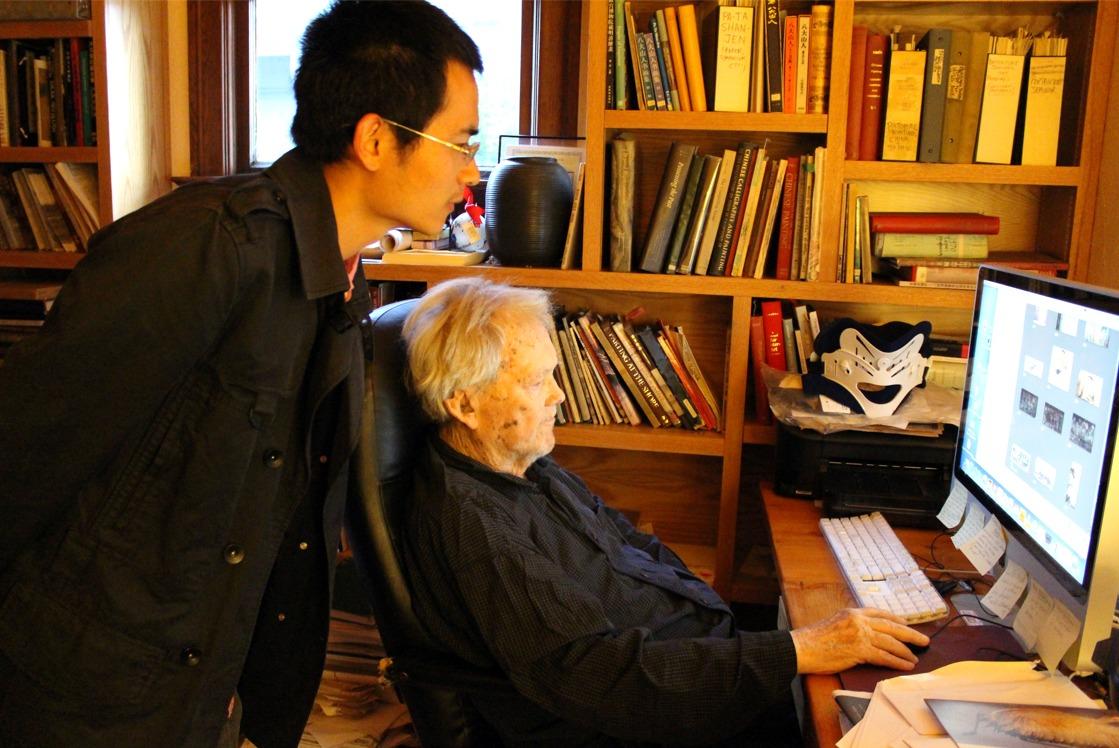

Cao Xun (middle), Huang Xiao (right) and Liu Shanshan pose for a photo at the National Library of China in 2010. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Cao Xun (middle), Huang Xiao (right) and Liu Shanshan pose for a photo at the National Library of China in 2010. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In a storage room in a museum in the United States, in the 1950s, a collection of Chinese landscapes painted by Zhang Hong in 1627 — The Zhiyuan Garden Album — quietly awaited its destiny. The 20 leaves featured a garden called Zhiyuan. The museum was considering the album for purchase until a young visitor introduced it to the world, realizing a dream that had haunted him for decades — the rediscovery of a garden that had long vanished — and starting a period of cooperation that would transcend time and space.

James Cahill, who would later become a recognized authority in Chinese art, was a postgraduate student at the University of Michigan at the time he saw the album, before it was split into separate folios and sold to different collectors.

At first, he did not pay it much attention. As a student of Chinese art, he understood that Zhang's paintings did not conform to orthodox Chinese standards of good composition or brushwork.

As Cahill explained, during a lecture at an exhibition to mark the regrouping of the separated leaves at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1996, it was not until a few years afterward that he realized that the 17th-century artist had sacrificed strong composition and brushwork to pursue "a kind of visual truthfulness".

A photo taken by Liu shows Huang and James Cahill at his home in Berkeley in 2013. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A photo taken by Liu shows Huang and James Cahill at his home in Berkeley in 2013. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Hailing the album as "incomparably the best visual evidence we have for a major garden from the great age of gardens in China", Cahill told the audience at the lecture that, although he was not able to identify either the artist's patron, or the location of the garden, he believed that according to the canals in the paintings, it might have been in Suzhou, Jiangsu province. For decades, he was unable to find evidence to support this theory.

In 1978, before China and the US officially established diplomatic ties, Cahill met Chinese garden historian Chen Congzhou in New York, where the latter was helping to create the Ming Xuan (Astor Court) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When Cahill showed Chen some leaves from the Zhiyuan album and photos of several others, the historian was "quite excited", Cahill wrote in a letter.

Chen said that he would like to work with Cahill to study the album. The two eventually lost touch, but not before the American could gift Chen with a set of black-and-white photos of the 14 paintings, which he later published in the opening pages of his comprehensive 2004 collection of articles on ancient Chinese gardens, Yuanzong, and which are the only photos in the book.

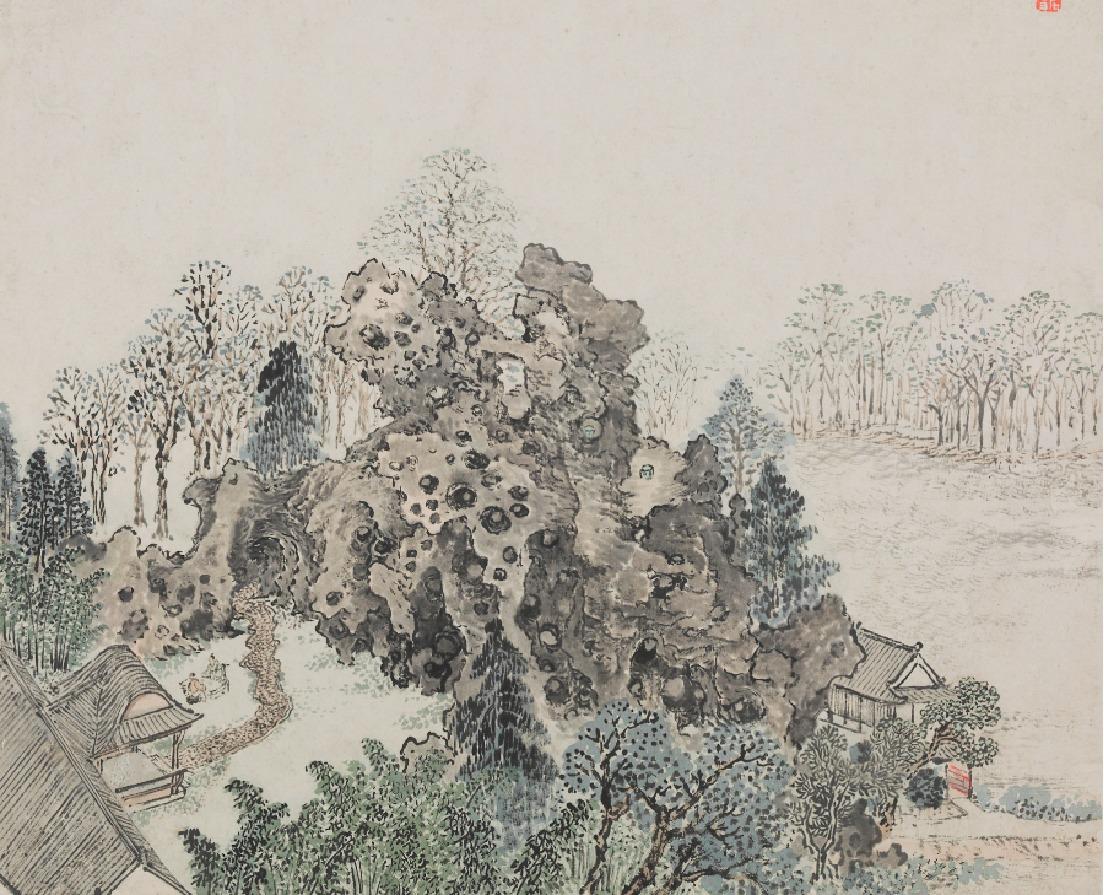

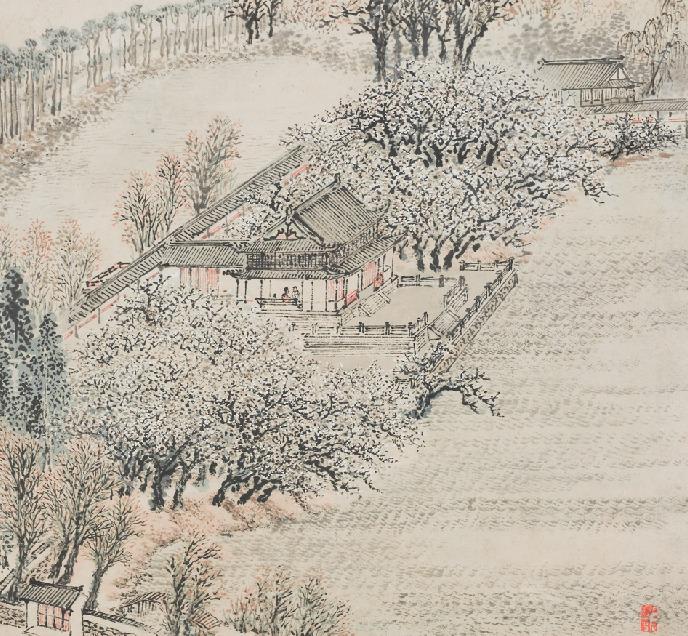

In The Zhiyuan Garden Album, Zhang Hong from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) depicted in 20 successive leaves a sequential experience of touring the Zhiyuan Garden along a certain route and enjoying the poetically named scenes, including pavilions, ponds and rockeries, among others. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In The Zhiyuan Garden Album, Zhang Hong from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) depicted in 20 successive leaves a sequential experience of touring the Zhiyuan Garden along a certain route and enjoying the poetically named scenes, including pavilions, ponds and rockeries, among others. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Detective work

When in 2010, Cao Xun, a professor of architecture at Tsinghua University, came across the only copy of the 800-page The Zhiyuan Collection amid the sea of old books at the National Library of China, he immediately thought of the photos in Yuanzong. Written by late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) author Wu Liang, who was a lay Buddhist and who adopted the name Zhiyuan, it is a collection of poems and essays, including the 3,000-word An Ode to Zhiyuan Garden.

Carefully comparing the details in the 14 photos with Wu's poems and essays, Cao became certain that Wu was the owner of the Zhiyuan Garden in Changzhou, which is also in Jiangsu province, and that there must be other leaves to the album. He asked two postgraduate students Huang Xiao and Liu Shanshan, to keep an eye out for any further information they could find.

In 2010, the SDX Joint Publishing Company brought out a series of books by Cahill. Liu and Huang found long discussions about the Zhiyuan album in the Chinese versions of The Compelling Image and Distant Mountains. At Cao's suggestion, they tried to reach Cahill via email to ask him about the album.

"We were just two kids, but surprisingly, Cahill replied. He was very excited about the discovery of An Ode to Zhiyuan Garden, and asked us whether we were serious about the research, and if so, he would send us his material on the garden," said Liu, an assistant professor at Beijing University of Engineering and Architecture, in a lecture about the newly published book Zhiyuan Mengxun (A Pursuit of the Dreams About the Zhiyuan Garden), which she co-authored with Huang, who is an assistant professor at the Beijing Forestry University.

In The Zhiyuan Garden Album, Zhang Hong from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) depicted in 20 successive leaves a sequential experience of touring the Zhiyuan Garden along a certain route and enjoying the poetically named scenes, including pavilions, ponds and rockeries, among others. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In The Zhiyuan Garden Album, Zhang Hong from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) depicted in 20 successive leaves a sequential experience of touring the Zhiyuan Garden along a certain route and enjoying the poetically named scenes, including pavilions, ponds and rockeries, among others. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Although Cahill had written the two books several decades earlier, his interest in the Zhiyuan Garden remained.

A month later, the pair received a package from the US in which they found a whole set of duplicates of the Zhiyuan album and the catalog of the 1996 exhibition, in addition to some 400 pages of literature and two CDs containing images of paintings of gardens that Cahill had collected over the years.

Over the course of almost two years, the trio exchanged 100 emails, researching paintings of Chinese gardens beginning with the Zhiyuan Garden, and discussing the structure, content and pictures of their collaboration fruit, a book eventually published in 2012 titled Garden Paintings in Old China.

"That book is a dialogue that transcends time and space," Liu says, "because we didn't meet until after it was published, and there was a time gap between Cahill's part and our part of the book. His was completed decades ago, and ours had only just been finished."

In 2011, Huang and Liu identified the former location of the 3.33-hectare garden in present-day Changzhou, but most of the land had since become a commercial residential area.

"It was a disappointment for Cahill, who had imagined that after finding the remains of the garden, with enough funding, and the addition of water, rocks and flowers, it would be possible to accurately re-create it according to Zhang Hong's paintings," Liu says.

In The Zhiyuan Garden Album, Zhang Hong from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) depicted in 20 successive leaves a sequential experience of touring the Zhiyuan Garden along a certain route and enjoying the poetically named scenes, including pavilions, ponds and rockeries, among others. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In The Zhiyuan Garden Album, Zhang Hong from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) depicted in 20 successive leaves a sequential experience of touring the Zhiyuan Garden along a certain route and enjoying the poetically named scenes, including pavilions, ponds and rockeries, among others. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In 2013, a digital model of Zhiyuan was completed and in 2015, the Museum of Chinese Gardens and Landscape Architecture made an intricate model of the garden to serve as a representative example of the private gardens in the southern reaches of the Yangtze River during the Ming Dynasty, alongside the model of the Old Summer Palace which represents royal gardens in northern China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Cahill unfortunately passed away in 2014, before the latter was complete.

"At a peak moment for Chinese gardens during the late Ming Dynasty, and designed by one of the greatest garden masters of the period, the Zhiyuan Garden was a milestone in Ming gardens," says Huang.

"It was a masterpiece that integrated artistic forms including literature, calligraphy and painting with the efforts of literati, painters and craftsmen," he continues.

"What's special about the garden is its rich use of water, its combination of garden styles from the north and south, the fact that it is grand and well-structured, and the romantic style used in the design of its rockery."

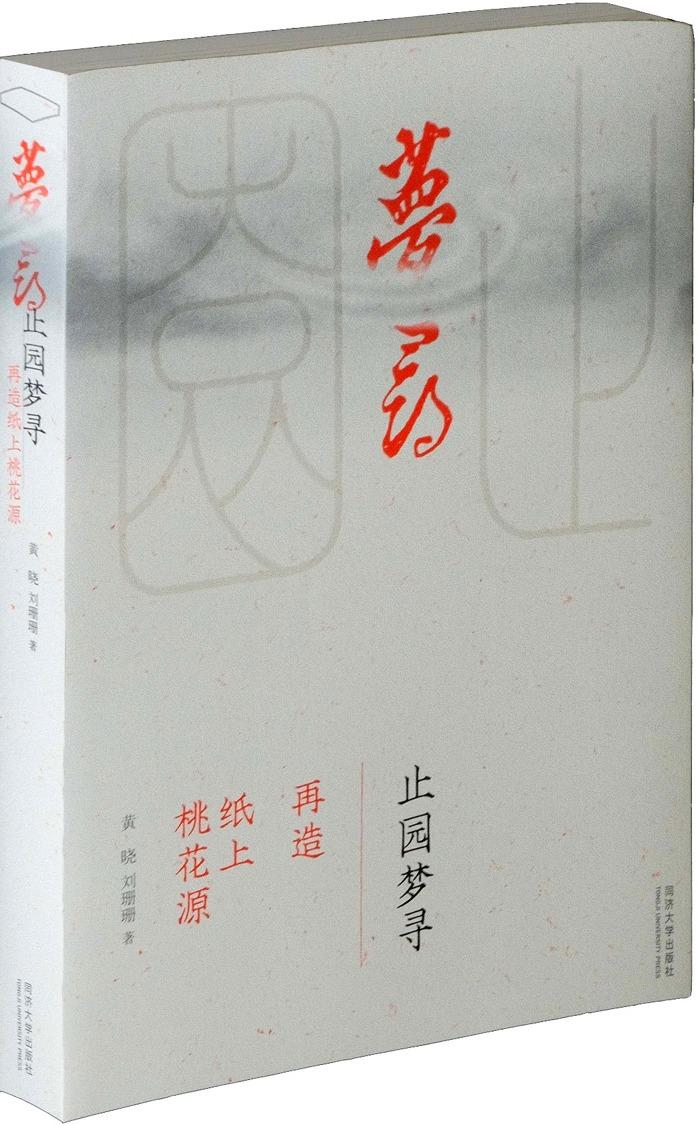

Zhiyuan Mengxun, a newly published book by Huang Xiao and Liu Shanshan devoted to the rediscovery of The Zhiyuan Garden Album. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Zhiyuan Mengxun, a newly published book by Huang Xiao and Liu Shanshan devoted to the rediscovery of The Zhiyuan Garden Album. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A reborn album

The fruit of the pair's research, Zhiyuan Mengxun, contains not only finely reproduced prints of the 20 paintings from the Zhiyuan album, but also five chapters respectively devoted to the story of the artist Zhang, Cahill and the album, the garden's philosophy and layout, its designer Zhou Tingce — who was a master garden designer of the time — and Wu Liang's family, whose history spans a period between the Ming Dynasty and today.

According to a pioneering researcher of Chinese gardens, Tong Jun, who was quoted by Huang and Liu in an article about the Zhiyuan Garden published in the Art Trade Journal in 2018, Chinese gardens are regarded as a fairyland and an idealistic world where one can liberate oneself from mundane worries and fatigue, and live a leisurely, elegant life.

"People often connect Chinese gardens with concepts of Taoism like tranquility and inaction that were advocated by Laozi, and with the sincerity and selflessness advocated by Zhuangzi. Meanwhile, we can also see in the gardens the order and hierarchy of Confucianism. For example, in the dominant buildings and the Chinese belief in the symbolism behind flowers and trees," the article reads.

"Like the yin and yang of tai chi, Taoism and Confucianism both exert an influence on Chinese gardens, shaping them into a perfect vehicle to represent the thoughts and lives of ancient people."

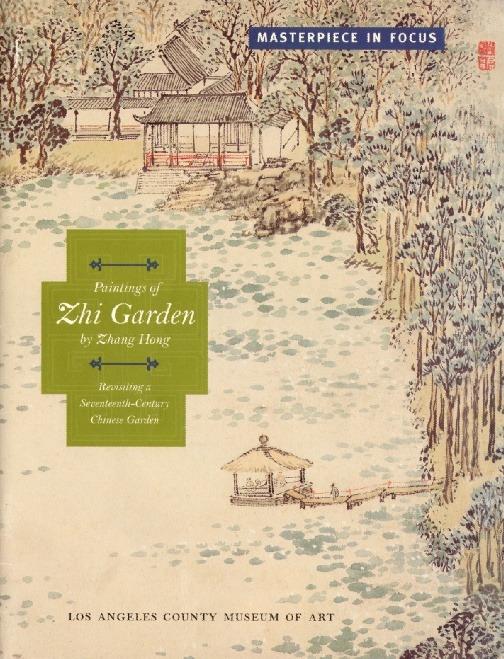

The exhibition catalog of the album of paintings shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1996. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The exhibition catalog of the album of paintings shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1996. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In 1610, 48-year-old Wu Liang, fed up with the factionalism of officialdom and feeling homesick, resigned from his position in North China, and returned to his hometown in Changzhou, in the hope of planting a garden where he could live in seclusion.

He invited Zhou to design it and named it Zhiyuan (a "garden for stopping", zhi meaning stop) after the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420) poet Tao Yuanming's composition Zhijiu (Stop Drinking Wine).

Zhijiu represents the idea of knowing when it is better to stop, advocated by both Taoism and Confucianism, Huang says.

The preface of The Zhiyuan Collection by Wu Liang in the late Ming Dynasty. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The preface of The Zhiyuan Collection by Wu Liang in the late Ming Dynasty. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Deeply influenced by this idea, Wu Liang ended his career to protect himself from political rivals. He became a lay Buddhist, taking on the name Zhiyuan and giving his 11 sons similar names that each included the character zhi.

Before Wu was reinstated in 1622, he spent 12 years in his garden. It was replete with symbols from the stories and poems of great writers of previous eras, and as he strolled through it, Wu would have been able to see these hidden allusions.

In his garden, Wu's spiritual world met with those of great ancients like Laozi from the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), Zhuangzi and Qu Yuan from the Warring States Period (475-221 BC), Wang Wei, Li Bai and Du Fu from the Tang Dynasty (618-907), and Su Shi from the Song Dynasty (960-1279), vividly illustrating the essence of Chinese gardens as the residence of the human spirit, Huang and Liu write in their book.

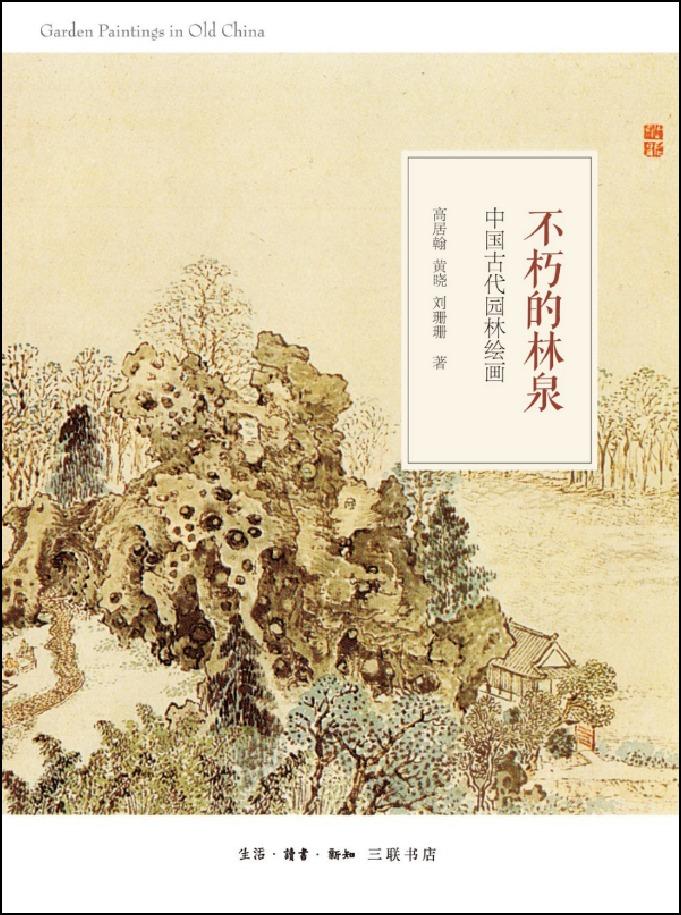

The cover of Garden Paintings in Old China, published in 2012. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The cover of Garden Paintings in Old China, published in 2012. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Among the great literati, the most important for Wu was Tao, whose fable Peach Blossom Spring is one of the earliest utopias described in Chinese literature, a place where people live harmoniously with nature, unaware of the outside world for centuries. Zhiyuan is Wuliang's Peach Blossom Spring, Huang and Liu write.

Wu was as wise to know when to stop his career, as he was to know when to stop his seclusion. In 1622, the 61-year-old left Zhiyuan, embarking on his next journey, losing his Peach Blossom Spring forever. He died in 1624.

In 1627, Wu's son Wu Rousi invited Zhang to paint the 20-leaf Zhiyuan album. In the centuries that followed, the garden disappeared, lost to the mists of time. Only in these paintings can people get a glimpse of the Chinese garden at its peak.

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn