Traditional craft still survives and prospers amid challenges, report Wang Ru and Zhu Lixin in Xuancheng, Anhui province.

Checking the quality of each sheet is one of the 108 procedures in making Xuan paper. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Checking the quality of each sheet is one of the 108 procedures in making Xuan paper. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Editor's note: There are 43 items inscribed on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage lists that not only bear witness to the past glories of Chinese civilization, but also continue to shine today. China Daily looks at the protection and inheritance of some of these cultural legacies. In this installment, we find out how the traditional craft of handmade Xuan paper still thrives in the digital era.

Zhou Donghong, 56, holds a finely woven bamboo screen with his partner. They steep it in a large trough full of pulp and lift it. A piece of moist Xuan paper takes form on the screen — known as a "mold and deckle" in the West. Then they carefully separate the freshly formed sheet of paper from the screen, spreading it flat out without any creases.

The whole process, called laozhi (getting paper out of water) in Chinese, only lasts a dozen seconds, but the adeptness actually comes from Zhou's experience of doing it repeatedly for nearly four decades.

The traditional craft of making Xuan paper cannot be replaced by machines, and every day when I work, I feel like I’m passing on the precious craft with my hands.

Guan Jiaming, artisan

This is one of the major steps to make Xuan paper, a traditional handmade paper in China. Made in Jingxian county, Xuancheng, Anhui province, the paper is made from a mixture of sandalwood bark, rice straw and stream water from the mountains.

Papermaking is the crystallization of wisdom of ancient Chinese people, regarded as one of the Four Great Inventions of China — along with gunpowder, the compass and printing techniques. Among various types of handmade paper in China, Xuan paper is famous for its close links to traditional calligraphy and ink paintings.

The traditional handicrafts of making Xuan paper were inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2009.

Although the process of laozhi seems simple, it is actually the most difficult step in making Xuan paper, with demanding technical details.

"The process of paper forming is the most difficult because I have to transform something intangible into something tangible, which means I need to scoop it out from the pulp and turn it into a sheet of paper. The thickness, uniformity and weight of this sheet are all controlled by my hands. In some way, my hands are just like a scale," says Zhou.

The skill can be mastered only through long hours and painstaking practice. Zhou admits soon after he started learning the craft as an apprentice in 1985, he wanted to give it up, since his hands would be covered in chilblains during winter as they constantly came into contact with cold water.

He could only apply ointment to relieve his pain at night, but the next day he had to continue his work. After a time, the skin on his hands would peel away.

After eight months, in 1986, he became an employee of the China Xuan Paper Group. Although he worked hard for a whole month, he did not receive any salary, because the paper he produced was categorized as not being up to the required standard.

Luckily, after finding a good teacher, and years of practice, he has honed his skills to the extent that 99 percent of the paper he makes meets the standard.

In 1993, Zhou was given the task to restore zhahua, an ancient type of Xuan paper renowned for being incredibly lightweight and "just as thin as cicada wings". One hundred sheets of zhahua weigh just 1.4 kilograms, less than half of the weight of ordinary Xuan paper. Zhou did a lot of reading and experiments, adjusting the concentration of paper pulp and the intensity of his movements continuously, and finally managed to re-create the paper.

Getting the paper out of water. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Getting the paper out of water. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Collaborative effort

Making Xuan paper is extremely demanding, and it takes nearly three years to produce a batch of it, through 108 procedures. An artisan can only skillfully master some of them in their lifetime.

For example, although he knows all the other procedures, Zhou, a master in laozhi, specializes in that one area and the procedures it entails, since each requires long-term practice to attain the necessary level of skill. As a result, the whole papermaking process requires collaborative effort.

Five people form a group, two for laozhi, two for shaizhi (drying paper) and one for jianzhi (checking quality of and cutting paper). Work results of the whole group are evaluated together. "There are high demands for the appearance, evenness and weight of the finished products. The weight of one piece of Xuan paper has only a 1-gram margin of error. Paper that does not meet the standard will be sent back for reproduction, and we will not get paid for it," says Zhou.

"It's all about group spirit, tacit understanding and mutual trust."

Drying and smoothing out the paper. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Drying and smoothing out the paper. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

The earliest record of Xuan paper can be found in On Famous Paintings Through the Ages, a book written by Tang Dynasty (618-907) scholar Zhang Yanyuan, in which he described the function of Xuan paper: It is a carrier of calligraphy and painting.

According to Huang Feisong, director of the Xuan Paper Research Center at the China Xuan Paper Group, based on clues in the historical record, Xuan paper was named after its main production area, Xuancheng.

"Xuan paper has many characteristics, like the ability to show different shades of ink, its stability, its durability and its resistance to insects, of which the first is the most prominent, and that's why it has been the favorite of calligraphers and painters through the ages," says Huang.

"The other features ensure it can be kept for ages, and that enables paintings, calligraphy, ancient documents and books to be passed down to the present day."

Checking the quality and cutting the sheets. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Checking the quality and cutting the sheets. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Chinese ink painter Li Xiaolong says that, when creating freehand brush paintings, showing ink variations is important. Some painters drip or splash ink like raindrops, and Xuan paper is the best for showing what they want to present.

"Xuan paper and artists are just like fish and water, which means they need each other. Xuan paper can show its quality through the creation of calligraphers and painters, and artists cannot give full play to their talent without Xuan paper," says Li.

According to Tang Shukun, director of the Handmade Paper Institute at the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei, capital of Anhui, calligraphy and ink paintings, especially freehand brushwork created on Xuan paper, have their unique appeal. As early as the Tang Dynasty, Xuan paper was listed as a tribute to the imperial court.

Checking printed paper pages. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Checking printed paper pages. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Tang mentions that as Chinese calligraphy and paintings developed, so did Xuan paper.

Jingxian became an important place for papermaking during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), according to Huang.

Traditionally, folk customs related to Xuan paper were common in Jingxian. For example, every year on the birthday and the date of death of Cai Lun, an official of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220) who is said to have invented paper, all the workshops in the paper industry pay tribute to Cai at a temple dedicated to him in the county.

Every year, when the workshops start work after Chinese New Year, people hold a ceremony to worship Cai as well, and gather for a meal, in the hope of a prosperous year and a thriving business. Following this tradition, alongside the feast people nowadays also set off fireworks.

Visitors get hands-on experience. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

Visitors get hands-on experience. (ZHU LIXIN / CHINA DAILY)

New vitality

The Xuan paper industry has seen steady development in Jingxian. Last year, about 500 metric tons of Xuan paper were produced in the county, and more than 30,000 local people are engaged with the industry.

Some younger people also play their role in this traditional industry, like Guan Jiaming, 33, who has been engaged with laozhi for more than a decade. "The traditional craft of making Xuan paper cannot be replaced by machines, and every day when I work, I feel like I'm passing on the precious craft with my hands," says Guan.

The local government is building a Xuan paper cultural park and a Xuan paper town to develop cultural tourism.

Since 2008, Tang has been carrying out field surveys with his team to check the condition of handmade paper workshops across China, and visited more than 500 papermaking workshops in over 300 villages.

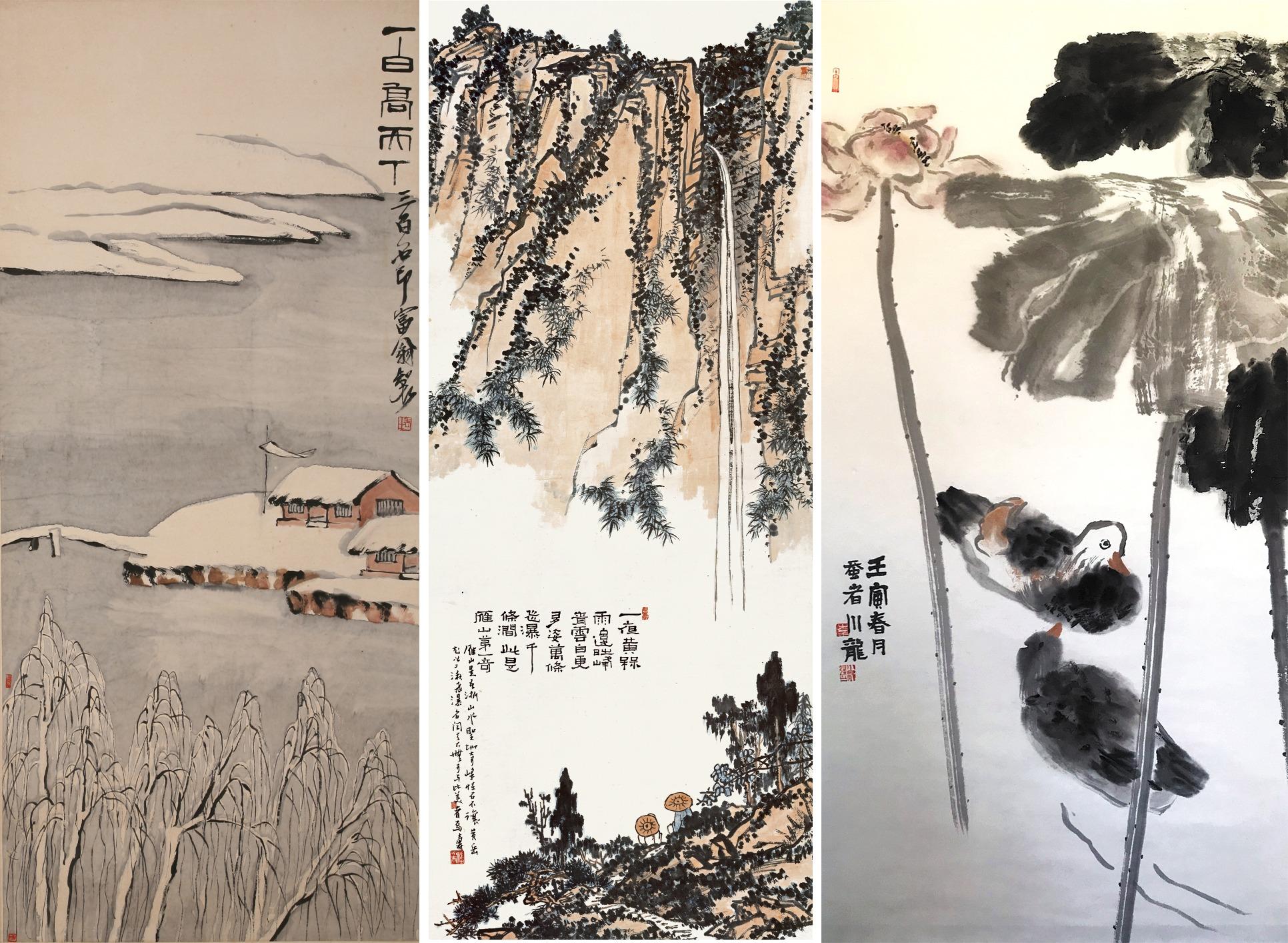

(From left) A part of Twelve-Screen Landscapes of Four Seasons by Qi Baishi, collected by Chongqing China Three Gorges Museum; the Splendor of Yanshan Mountains by Pan Tianshou, collected by the Art Museum of China Academy of Art; an ink painting by Li Xiaolong. (PHOTOS PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

(From left) A part of Twelve-Screen Landscapes of Four Seasons by Qi Baishi, collected by Chongqing China Three Gorges Museum; the Splendor of Yanshan Mountains by Pan Tianshou, collected by the Art Museum of China Academy of Art; an ink painting by Li Xiaolong. (PHOTOS PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

According to Tang, from the 1990s to 2010, the handmade paper industry suffered a heavy blow with the industrialization and the development of the internet, which lead to mass, mechanized production of paper and a decline in demand for handmade writing paper.

At least 90 percent of the handmade paper companies and workshops closed in the country, but a resurgence is underway.

He finds a new coordination between supply and demand. "I'm optimistic about the development of handmade paper, like Xuan paper. Although the demand has shrunk a lot, there are still reliable customers," says Tang.

"With modern technology, the shrinking of this industry is an inevitable trend across the whole world. But China, the birthplace of papermaking, still leads in the world when it comes to the number of workshops and people engaged with papermaking by hand, according to our research.

"Actually, over the past decade, many types of traditional handmade paper crafts have found new vitality. They attract people with their rich cultural connotations," says Tang.

Contact the writers at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn