An exhibition at the Palace Museum demonstrates how civilizations advanced together, Wang Kaihao reports.

A group of Tang Dynasty (618-907) sancai statues of camels and horses in the central hall of the Meridian Gate Galleries in the Palace Museum in Beijing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

A group of Tang Dynasty (618-907) sancai statues of camels and horses in the central hall of the Meridian Gate Galleries in the Palace Museum in Beijing. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Blue-and-white porcelain is probably a good example of the global market in the ancient world. This Chinese ceramic variety gained a global reputation during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and over the following centuries, became one of the country's signature products on the flourishing Maritime Silk Road.

Orders from overseas poured into Chinese kilns, and many countries along the trade routes also made their own variants.

Bronze was mainly used in West Asia to make tools and weapons, but in China it developed into a complicated system of ritual artifacts.

Ji Luoyuan, exhibition’s curator

Nonetheless, when people look back at how this saga began, they may discover an interesting fact — this "made-in-China "product was also an example of the international supply chain in the past, as the raw cobalt pigment initially used to make its amazing blue came from modern-day Iran.

This is just one of the stories told through the 266 cultural artifacts on display at Historic Encounters: Interaction Between China and West Asia in History, an ongoing exhibition running through April 11 in the central hall of the Meridian Gate Galleries in Beijing's Palace Museum, also known as the Forbidden City.

"In the blue-and-white porcelain on exhibit, you'll find many typical West Asian decorative patterns and inscriptions," Ji Luoyuan, the exhibition's curator and an associate researcher with the Palace Museum, says.

"But China gradually developed its own materials during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and adopted more traditional Chinese patterns," he adds. "The craftsmanship and aesthetics of blue-and-white porcelain then became more localized. Chinese civilization has always been inclusive and creative."

Exhibited blue-and-white porcelain demonstrates cultural exchanges between China and West Asia during ancient times. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Exhibited blue-and-white porcelain demonstrates cultural exchanges between China and West Asia during ancient times. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Chemistry between China and West Asia occurred long before that. For millennia, the rise of metallurgy in West Asia greatly influenced its counterpart in China.

"Distinctive West Asian elements thus surfaced on Chinese bronze vessels and weapons, as well as on gold and silver items," Ji says.

How much influence a civilization accepts depends on whether it has an open mind and an inclusive attitude toward others.

Wang Guangyao, a researcher at the Palace Museum

Nonetheless, as Chinese civilization favored order and harmony from the start, ritual was particularly highlighted.

"That explains why bronze was mainly used in West Asia to make tools and weapons, but in China it developed into a complicated system of ritual artifacts," Ji adds.

The millennia-old ceremonial bronze musical instruments from the Palace Museum's own collection take visitors back to Confucius' time to appreciate the ways that the cold metal inspired the imaginations of Chinese sages, resulting in a time of great thinkers.

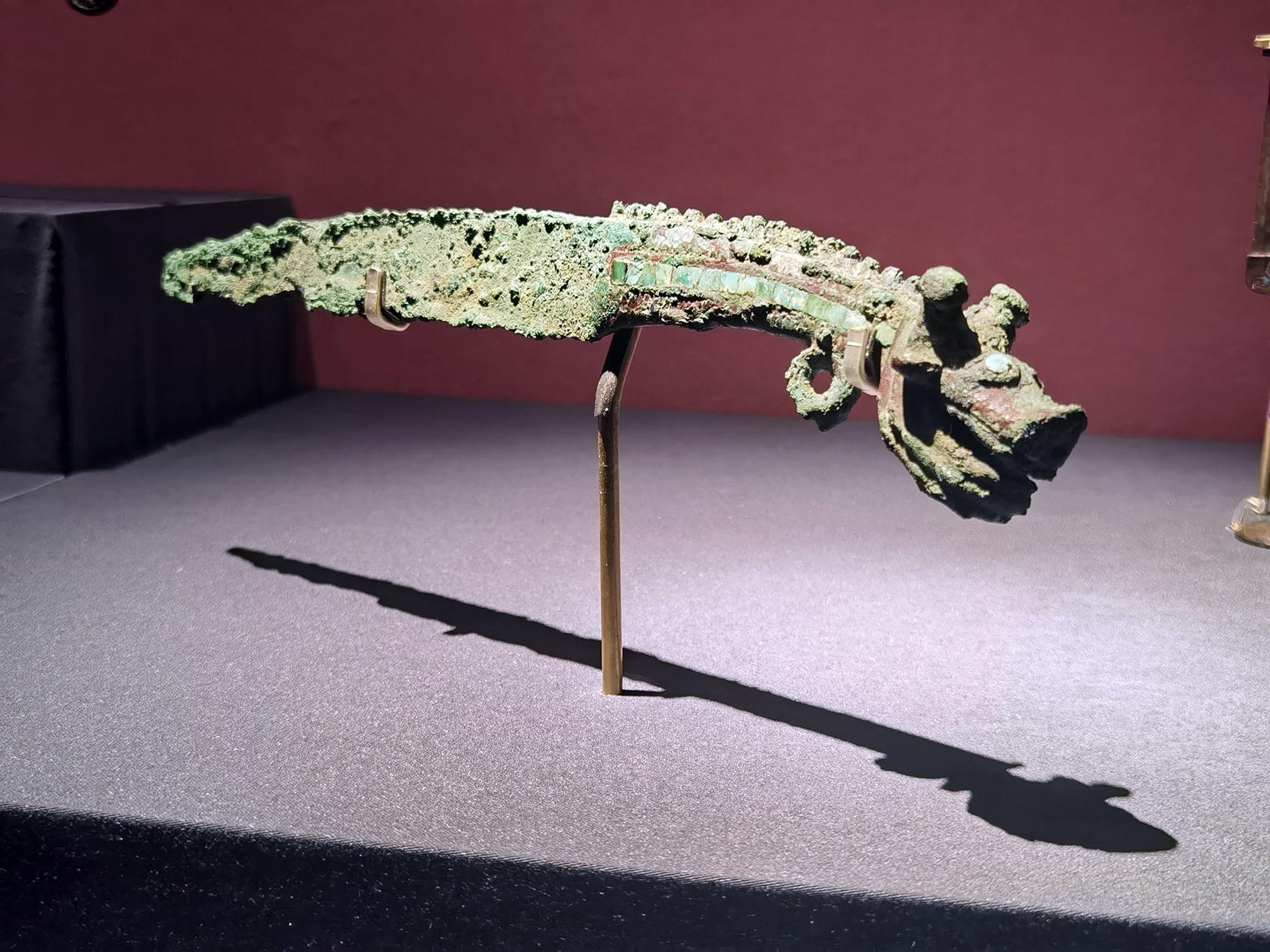

Though smaller in size and rougher in appearance, one of the bronze daggers on display may prove equally amazing. Carved in the shape of dragon head with a pair of turquoise eyes, the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC) dagger, which displays typical elements from both China and West Asia, hints at the kind of cultural exchanges that occurred across the Eurasian grasslands before recorded history.

A Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC) bronze dagger inlaid with turquoise eyes reflects early-stage communications between China and West Asia. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

A Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC) bronze dagger inlaid with turquoise eyes reflects early-stage communications between China and West Asia. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Just as bronze, which originated in West Asia and once enriched the genes of ancient Chinese civilization, silk from China may also have shaped the path of development on the other side of the continent, as it once inspired caravans to endure the tough desert crossing in search of wealth.

An ivory sculpture of a silkworm, unearthed from the 5,300-year-old Shuanghuaishu site in Henan province, tells the early chapters of the silk legend, while other exhibits explain its sequel.

"Chinese silk continued to spread westward, but Chinese artisans also absorbed elements of textiles from West and Central Asia and used them to improve their own patterns and techniques," Ji says. "The communication was in two directions."

A group of textiles unearthed in the present-day Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region were chosen to directly reflect this mix.

"Ancient artisans in West Asia may not have known silk weaving techniques, but their skill at weaving wool was introduced to China and adopted to make silk pieces," the curator explains.

In the Tang Dynasty (618-907), Chinese silk borrowed patterns then popular in West Asian textiles, which had a lasting influence on the later development of the silk industry.

Pottery figurines showing caravans on the ancient Silk Road. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Pottery figurines showing caravans on the ancient Silk Road. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Glass was another major cultural ambassador between China and West Asia. Though glass beads were introduced to China, becoming part of the collections of nobles as early as the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC), it only became a key import after the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) when trade along the Silk Road and Maritime Silk Road routes thrived. As a result, Chinese artisans were inspired to make glass products of their own.

A graveyard in Datong in today's Shanxi province, which was once the capital city of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534), has yielded many pieces of exquisite glassware, as the exhibition shows. During the fifth century, when the city was known as Pingcheng, it was a hub for glass production.

Ji says that the use of precious glass vessels was also localized after their arrival in China. For example, after glass perfume bottles were introduced to China from Persia, they were popular at Buddhist temples for use during the worship of sacred relics.

One highlighted exhibit is a typically Islamic-style glass plate dating back to the Tang Dynasty. It was found in the underground palace of the Famen Temple in Xi'an in Shaanxi, and may prove surprising for its inclusion in a royal Tang Buddhist temple.

"How much influence a civilization accepts depends on whether it has an open mind and an inclusive attitude toward others," Wang Guangyao, a researcher at the Palace Museum, says.

An enameled and gilded glass vase with ancient Islamic patterns. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

An enameled and gilded glass vase with ancient Islamic patterns. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

In the center of the gallery, a cluster of Tang pottery figurines known as sancai grab attention. They include figurines of camels and merchants from West and Central Asia. In spite of their age, their glaze and vividly portrayed facial expressions still seem fresh, and remind people of the importance of exchanges.

These pioneering merchants may have disappeared into the dust of time, but the routes they once explored have become immortal. In the New Book of Tang, the official history of the dynasty compiled by the famous 11th-century historian and poet Ouyang Xiu, different routes from China to the Arabian Peninsula are recorded, along with various countries and their distances.

A copy printed in the Forbidden City in 1739 is on display near the entrance of the exhibition as a teaser.

"Civilization means that a group of people inspire their surrounding areas to prosper as they achieve development," Wang explains.

"Interactions between ancient China and West Asia not only benefited each other, but also influenced other regions and contributed to their shared growth," he says.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn