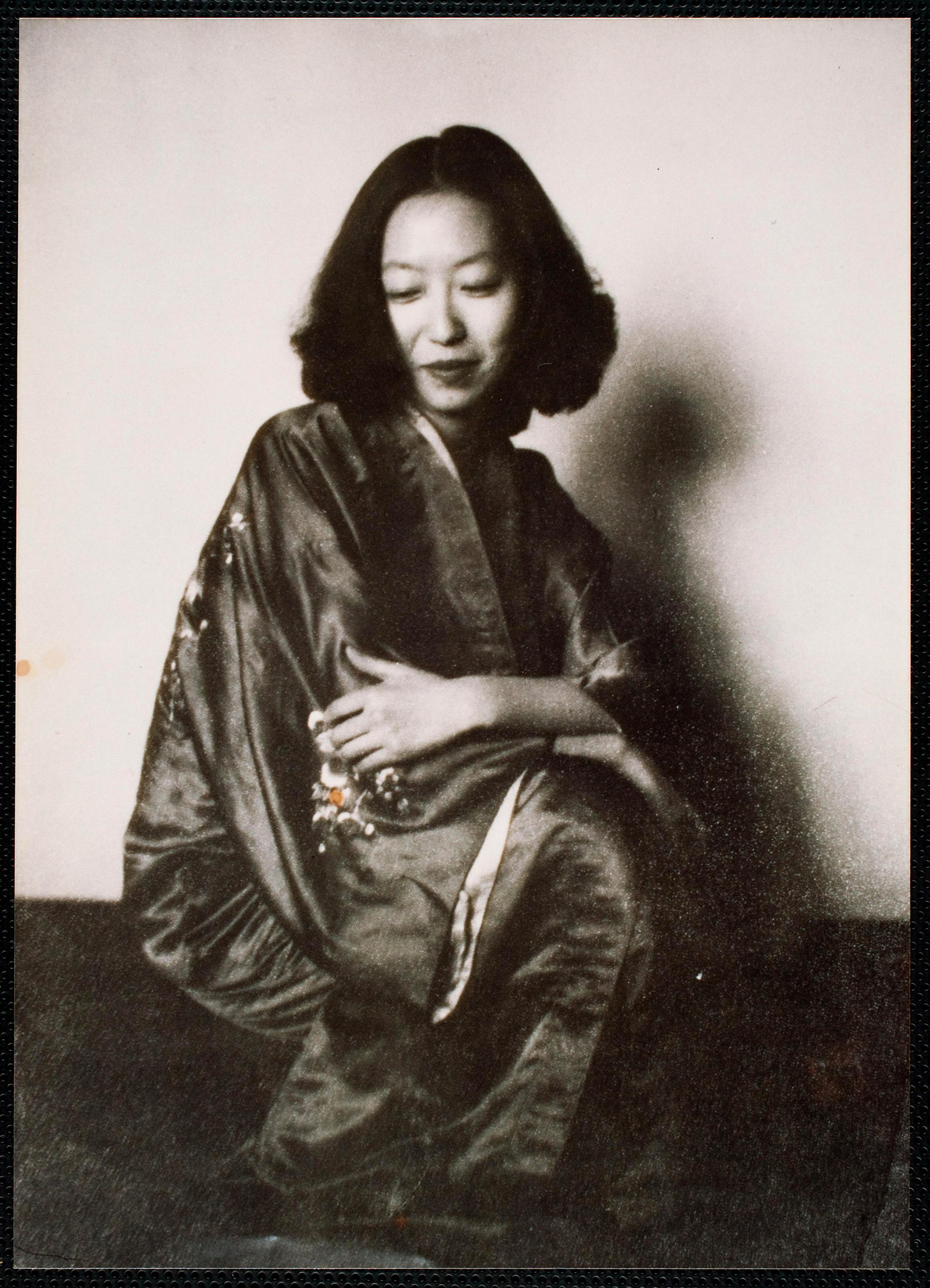

A collection of manuscripts, letters and other documents recently acquired by the University of Southern California promises to shed new light on the later years of the iconic Chinese writer Eileen Chang. Mariella Radaelli reports.

The East Asian Library of the University of Southern California (USC), based in Los Angeles, houses a number of manuscripts by Eileen Chang (1920-95) — an iconic Chinese writer hailed for her vivid portrayal of life in Hong Kong under the Japanese occupation in the early ’40s. The USC probably holds the most extensive archival collection of Chang’s papers anywhere in the world, certainly in the United States.

Recently, the USC acquired more documents that are likely to shed light on Chang’s later years spent in Los Angeles, where she had settled in 1972 and lived until her death in 1995.

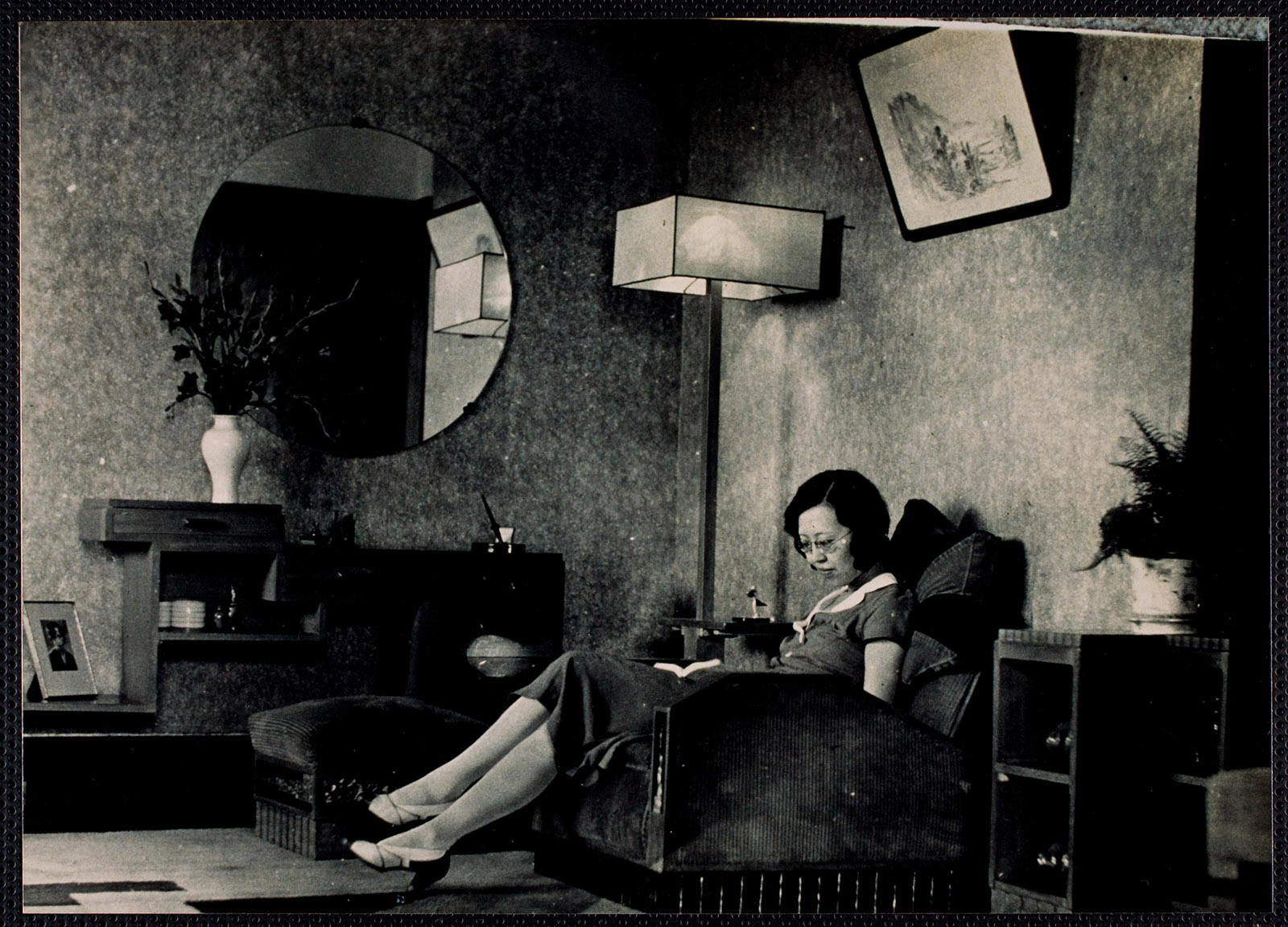

Chang led a reclusive life in her Rochester-Avenue apartment in the Westwood neighborhood, preferring to keep in touch with people through letters rather than meeting them in person. “Toward the end of her life, Chang was taking great precautions to avoid being bothered by visitors,” says Kam Louie, honorary professor at the University of Hong Kong’s School of Chinese and editor of the essay collection, Eileen Chang: Romancing Languages, Cultures and Genres. Sometimes Chang would spend the nights in motels where nobody would recognize her.

When Chang’s body was discovered on Sept 8, 1995, she had been dead for a few days. “Friends said that Miss Chang, known to Chinese readers as Chang Ai-ling, had died of natural causes several days before her building manager discovered her body after becoming alarmed that she had not answered her telephone,” read The New York Times obituary, published in the paper’s Sept 13, 1995, edition.

Dominic Cheung, a professor of Chinese literature at the USC at the time, was a keen reader of Chang’s writings, and though “respectful of Chang’s reclusive lifestyle, he never met her,” says Tang Li, head of the USC’s East Asian Library. After Chang’s death, Cheung supervised the sea burial, as per the deceased’s wishes, as well as the shipping of her belongings, bequeathed to Stephen and Mae Soong in Hong Kong.

Stephen was a playwright, translator and film producer. “The Soongs were long-time supporters and confidantes of Chang’s,” remarks Nicole Huang, professor and chair of the Department of Comparative Literature at HKU.

“Recognizing the significance of Chang’s literary legacy, Cheung collaborated with the Soongs, who donated a rich repository of essays, speeches, correspondences, manuscripts and photographs, establishing the special collection known as Ailing Zhang Papers in the USC’s library,” Li says. Cheung helped the library acquire the six boxes that the collection was started with and recently donated materials that went into a seventh.

The latest haul of acquisitions comprises 15 folders containing documents on Chang’s move to the US in 1955 and her subsequent marriage to American screenwriter Ferdinand Reyher the following year. They also include photos of her Rochester-Avenue residence and even grocery receipts. Her medical records and correspondences from 1991-1995 can be found in Folder 4.

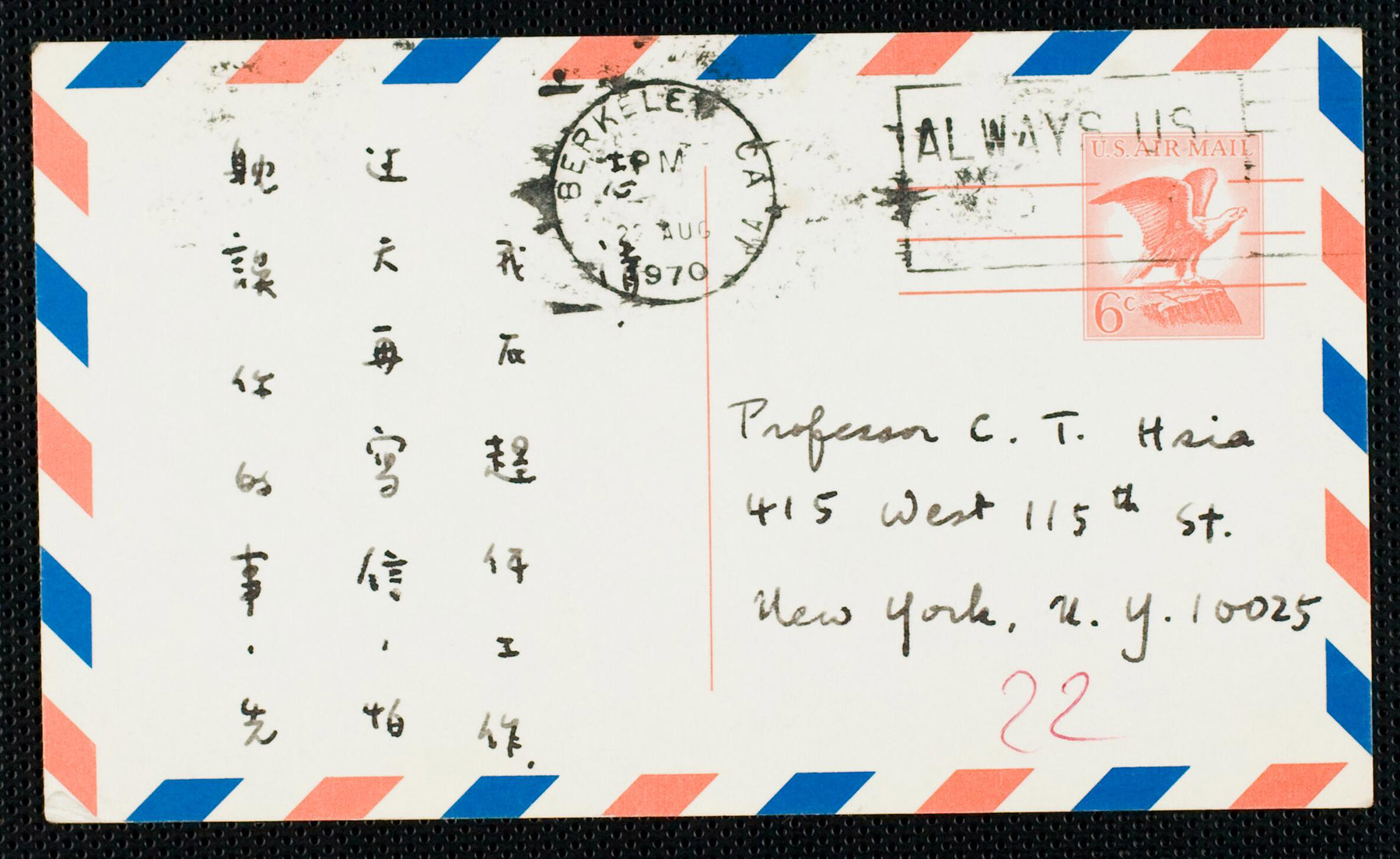

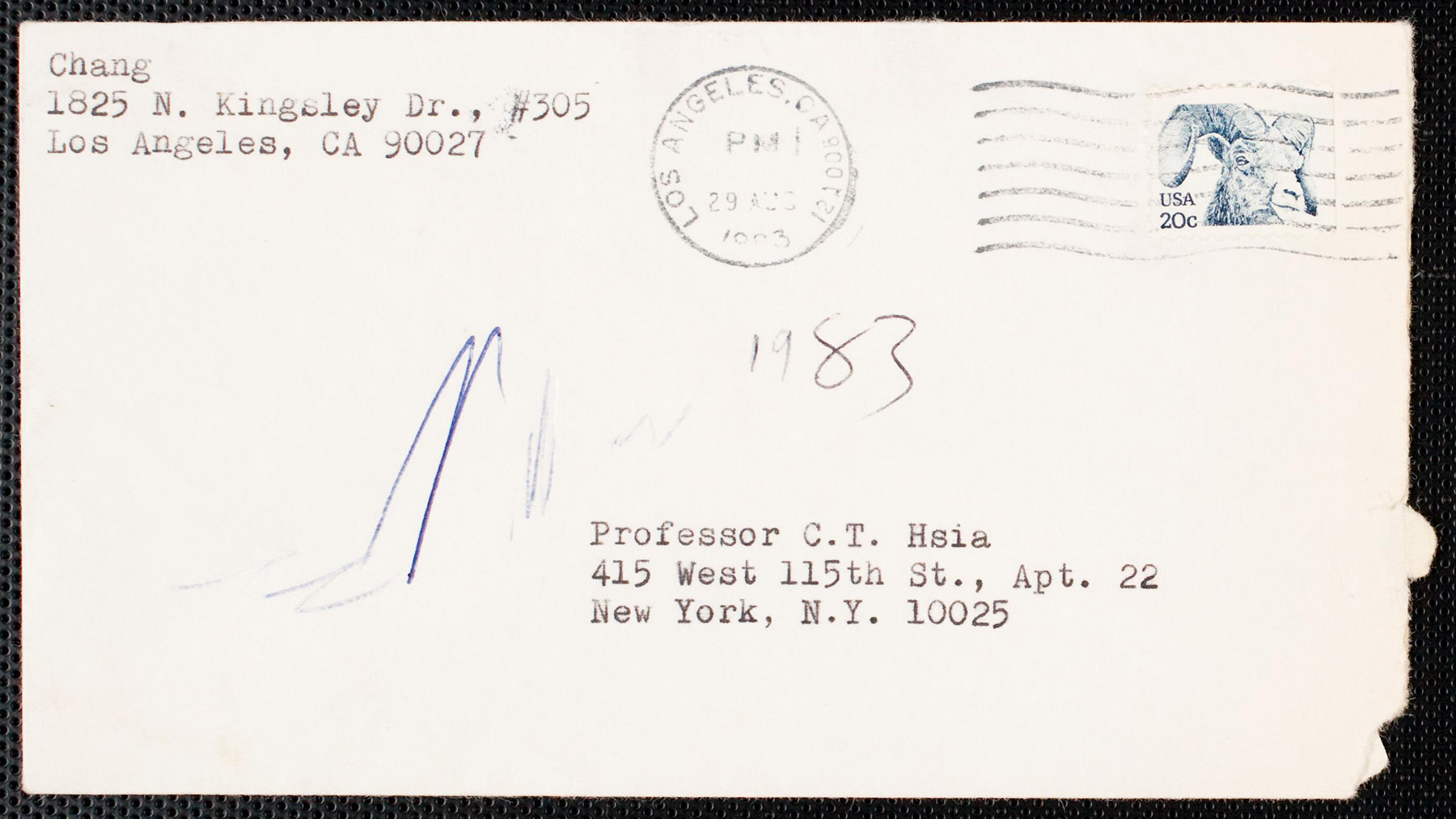

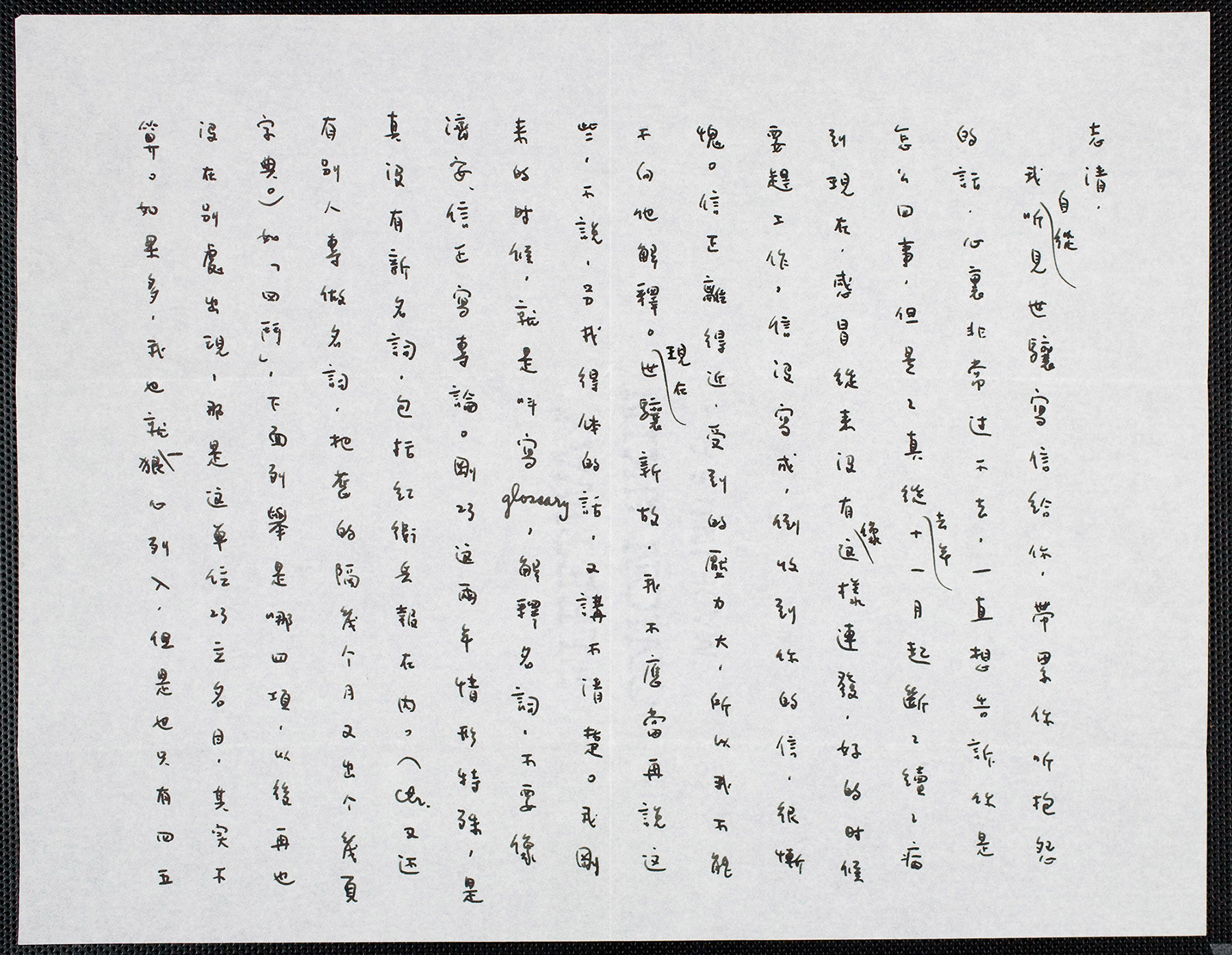

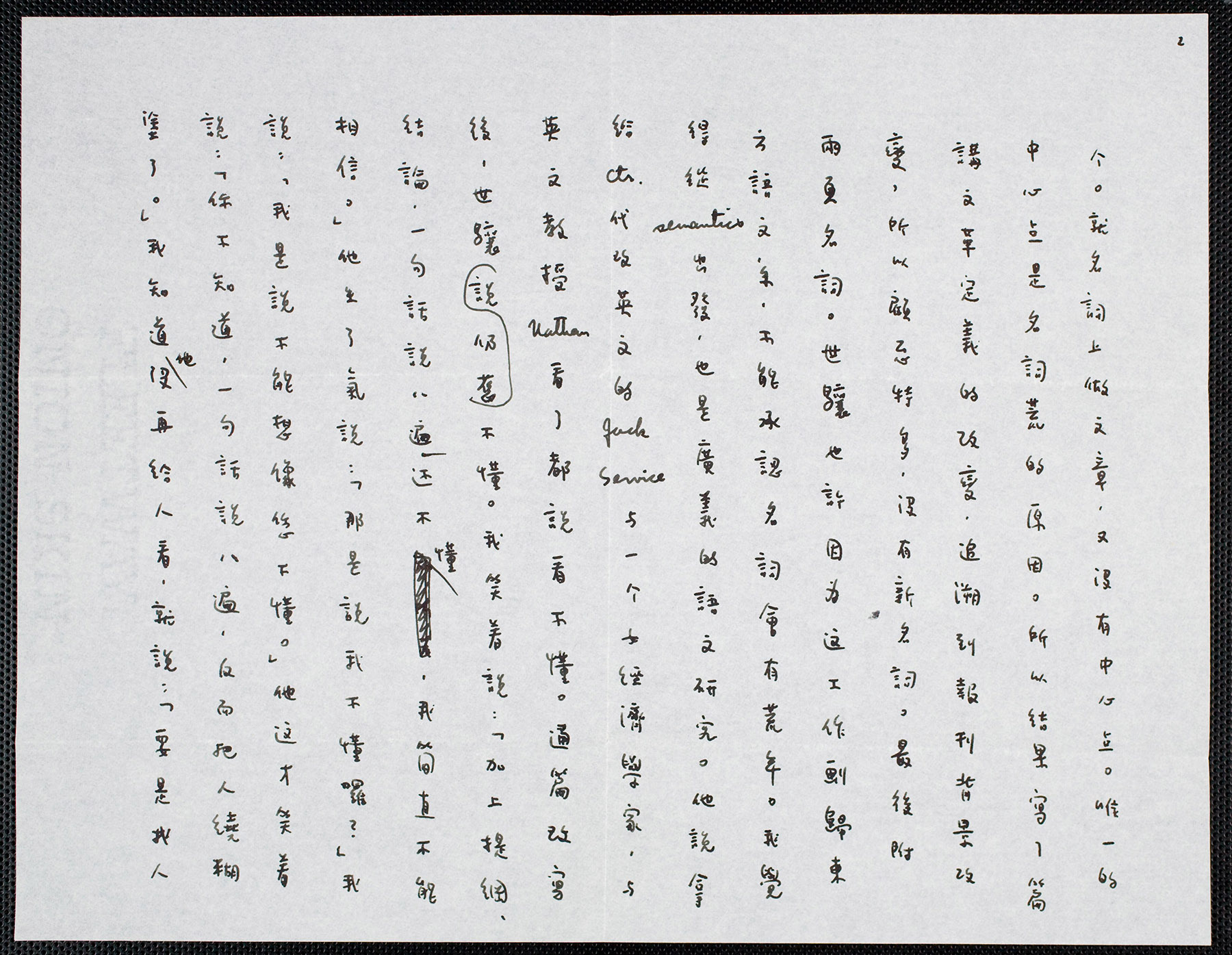

Highlights of the USC’s new acquisitions include several among the 118 letters Chang had written to historian and literary critic CT Hsia, who played a major role in reviving interest in the writer’s works in the ’60s. In these letters, Chang went beyond sharing her thoughts on the essays and books she was reading at the time, discussing personal matters. In many of them, she made repeated requests to Hsia to make sure that her address was kept a closely guarded secret.

Folder 13 contains some of the letters exchanged between Chang and her brother, Zhang Zijing, from 1991-94. Chang’s letters to scholars Chuang HC and Stephen Cheng, written in the ’90s, are in folders 10 and 11.

“The contents of this donation provide indispensable information about Chang’s living conditions in Los Angeles, which remain a mystery even today,” Cheung said to a bunch of researchers recently.

The new additions to Chang’s papers in the USC collection makes it a veritable treasure trove for those with an academic interest in the writer. “We expect researchers to come in and comb through the original materials and then publish their findings,” says Tyson Gaskill, director of the USC Libraries.

Pivoting around Hong Kong

A descendant of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) statesman Li Hongzhang on her father’s side, Chang was born in Shanghai. Her mother, a Europhile bohemian, was largely absent from her children’s lives. Chang’s father was abusive toward her and an opium addict. In her nonfiction book Whispers (1944), the writer describes her time spent at her father’s home as a “languorous, ashen, dust-laden” way of living. Unsurprisingly, dysfunctional families recur in Chang’s works, notably in The Golden Cangue (1943), which Hsia calls “the greatest novelette in the history of Chinese literature”.

Chang enrolled at HKU in 1939 to study English literature. Her college education was interrupted in December 1941, when the Japanese army completed the occupation of the fallen British fortress of Hong Kong. Chang had to head back to Shanghai as a result.

In 1952, she had returned to Hong Kong to work as a translator of Cold War propaganda for the United States Information Service. “In the ’50s, Chang got serious about publishing her works in English, thereby embarking on her long-cherished ambition to become a world writer,” says Julia Chan, professor of English at Lingnan University. Chang’s second Hong Kong sojourn lasted three years before she moved to the US. She struggled for some time, trying to find a suitable job in America. Chang was back in Hong Kong for the third time in 1961. Since Chang could not get an academic position without a university degree, Stephen Soong, who was on the screenwriting committee of the International Films Distributing Agency, commissioned her to write screenplays.

In a letter written to Mae Soong, Chang shares her worries about her future: “One day, I came across the results from the divination I did last time, and it said that my luck would not turn better until 1963! … Don’t you think I will wait for luck until I die?”

But luck did come her way when Hsia, who was teaching at the Columbia University, praised Chang’s literary works over 40 pages in his seminal 1961 book A History of Modern Chinese Fiction, 1917–1957. In it, Hsia refers to Chang as “the best and most important writer in Chinese today”. In 1969, the professor recommended her for a job as a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. “Hsia once commented that Chang’s greatest faux pas was to lose interest in humanity in her later life,” Chan points out.

Isolation is not a tragedy

But was it Chang’s troubled childhood, during which she was ignored by her mother and tortured by her father, that made her turn into a recluse later in life?

Carole HF Hoyan, a professor of Chinese literature at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says while it’s difficult to pinpoint what caused Chang to withdraw into her shell, growing up in a dysfunctional family is likely to have left a few scars.

Chan refers to Chang’s essay collection Whispers, in which she describes her experience of getting beaten up and held captive by her opium-smoking father, of nearly dying of gastroenteritis, and eventually escaping from the clutches of her father and stepmother. The story of her running away from her father’s home, which Chang re-creates in great detail in her thinly disguised autobiographical novel, The Fall of the Pagoda, published posthumously in 2010, “is paradigmatic of her resilience and preference for self-reliance in times of distress,” Chan says. In several of her works published in the ’40s, Chang writes about lonely, abandoned women. It was almost as if she foresaw living a solitary life in LA many years later. However, there is no reason to assume that she was unhappy about the isolation she had consciously chosen for herself.

Chan remarks that in her 1944 essay Writing of One’s Own, Chang had emphasized that being alone — the state in which the characters in her works often find themselves — was not necessarily a tragedy.

“The characters in Chang’s fictional works — Aloeswood Incense: The First Brazier (1943), The Golden Cangue (1943), or Red Rose, White Rose (1944) — ultimately end up in a despondent, frustrated existence,” Chan says. “Tragedy offers closure, which is precisely what her characters do not get. There is no grandiose sacrifice, poetic justice, heroic gestures in Chang’s works. Characters continue living, unhappily perhaps, but no calamity befalls them.”

Chang’s own life, especially in her later years, seemed to imitate those of the characters she had written. Her papers in the USC’s collection are a testament to her integrity and courage as demonstrated in her ability to go it alone, until the very end.