Northwest University archaeologists trace stories of exchanges in Central Asia along the ancient Silk Road

More than 2,000 years ago, on a mission of peace and to bolster exchanges, an envoy from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) named Zhang Qian (164-114 BC) entered the heart of the Eurasian continent.

Embarking from the capital Chang’an — modern-day Xi’an in Shaanxi province — on his arduous and pioneering journey in 138 BC at the request of the then emperor, Zhang was in search of the Greater Yuezhi, nomads who migrated from China to Central Asia during the Han Dynasty. He aimed to persuade the Greater Yuezhi to establish an alliance.

He finally reached the destination, and thanks to his diplomatic trek across Central Asia, the long, historic saga of the Silk Road began.

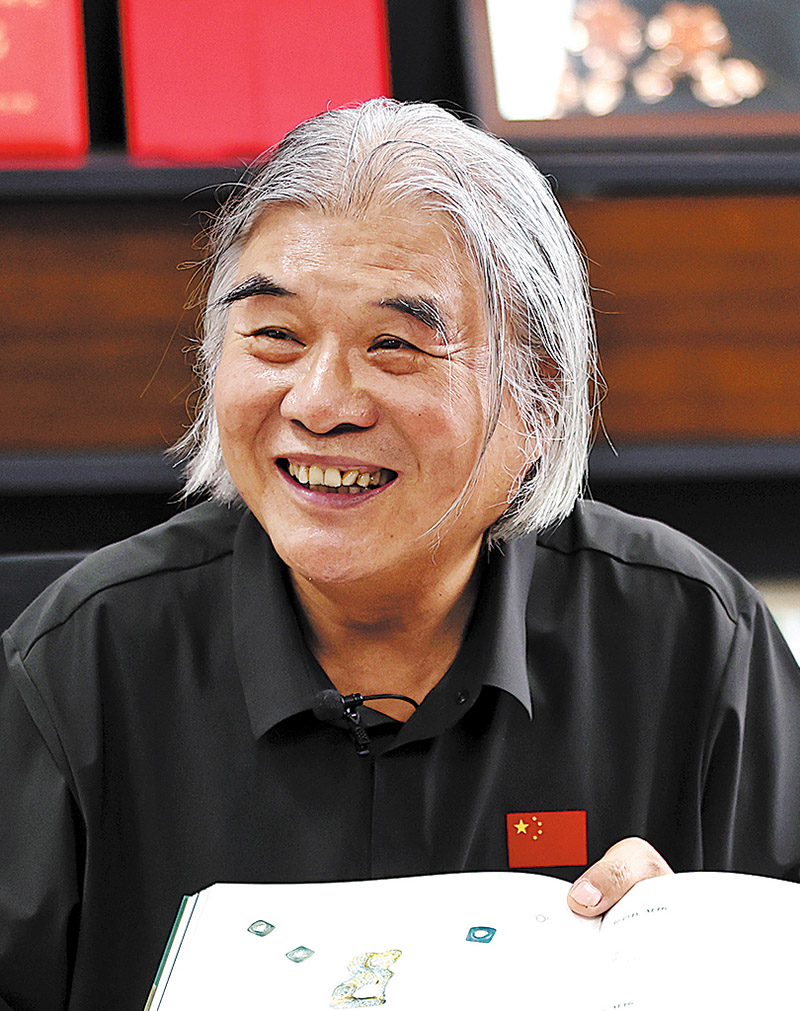

Centuries have passed since then, and sand and time have hidden much history. But for the past 15 years, Wang Jianxin, an archaeology professor at Northwest University in Xi’an, has been working on sites that may have played a part in long-forgotten stories.

Working with Central Asian counterparts, he and his team have gradually put together some of the jigsaw pieces scattered along the Silk Road, giving a new perspective on studies of its routes, and revealing cultural exchanges from past to present.

“For a long time, the modern study of the ancient Silk Road seems to be led by Western countries,” Wang said. “But since this network of ancient trade routes connected the East and the West, the voices of Asian scholars, especially from the routes’ starting points in China, are at least of equal importance.”

Central Asia was a core section along the ancient Silk Road. Since it is located in the middle of the Eurasian continent, it serves as an intermediary between Eastern and Western civilizations, and many different ethnic groups and cultures converge on the region, Wang said.

Following in Zhang’s footprints, Wang and his team started by looking for the Greater Yuezhi, to clarify its history. The group is only recorded in Chinese literature, and the whereabouts of any remains associated with it were unknown to archaeologists. In 2000, they began excavations in northwestern China, where they identified the main Greater Yuezhi settlement on the eastern edge of the Tianshan Mountains.

They continued their work in Central Asia, discovering the remains of a Central Asian kingdom that existed from the 1st century BC to the 5th century AD, and known in Chinese as Kangju, at the Sazagan Site in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. They also found a Greater Yuezhi site to its south at the Rabat Site in Boysun, Uzbekistan.

Based on their experience, Wang’s team has proposed new theories and methods for studying nomadic groups, which focuses on seeking settlements. “Unlike the normal understanding that nomadic people generally didn’t maintain stable settlements, we discovered that those living in the Eurasian grasslands did, so they could rest during the winter,” Wang said.

“The region can be extremely cold for long periods of time in winter, so how could nomadic people continue to use pastures? As a result, we believe they sought warmth in settlements, to prevent their livestock from freezing. Such a great loss would affect them for life,” he added.

Guided by this theory, the team discovered several nomadic settlement sites in the Samarkand Basin in 2014, an area an archaeological team from Italy had studied for 15 years without finding such sites.

The process involves conducting multiple surveys over wide areas and conducting small-scale, more precise excavations. Wang said that the surveys are vital to familiarizing them with the environment and distribution of remains, and to improve understanding of previous findings.

“With the understanding accumulated from surveys, we can find the blanks in previous studies, then contribute our efforts, fill in the blanks, and solve key problems. In this way, almost each excavation leads to a breakthrough,” Wang said.

He said that when he and his team work with Central Asian scholars on archaeological surveys, they are often divided into two groups, one composed of local scholars, who visit villagers

to find out if they have discovered any artifacts, and a group of Chinese scholars who survey the surrounding land, or part of it.

“This way, we give full play to each other’s strengths and our cooperation often leads to important discoveries,” Wang said.

During the 15 years working in Central Asia, the team has worked with all five of the region’s countries. Its studies are now extending to West, South, and North Asia.

In 2023, Northwest University set up the Collaborative Research Centre for Archaeology of the Silk Roads to enhance archaeological work with countries along the Silk Road. It has since opened the China-Central Asia Belt and Road Joint Laboratory on Human and Environment Research in Uzbekistan to improve cultural heritage and geology studies along the Silk Road.

According to Wang, cultural exchanges in Central Asia and the present-day Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in China actually started much earlier than Zhang’s time.

Important archaeological evidence for the process exists in the form of wheat and barley, which originated in West Asia and were brought to the Yellow River Basin about 4,000 years ago. At the same time, millet from China traveled to Central Asia, the Indus Valley, West Asia, North Africa, and Europe, according to archaeological findings.

“This means that much before the creation of the Silk Road, communication and transport between the East and the West already existed. This is the period also believed to have been when early Chinese civilization originated,” Wang said. “As a result, communication played a role in the formation and evolution of Chinese civilization.

“Studying Chinese civilization requires understanding civilizations in other parts of the world. This is the significance of engaging in cultural exchange and mutual learning between civilizations,” he added.

As the study of the Greater Yuezhi made important progress, Chinese archaeologists began to pay closer attention to the Fergana Valley in 2019 — the valley runs through parts of present-day Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

It has yielded evidence of Dayuan, the Chinese name of an important Hellenistic state in Central Asia that existed during the Han Dynasty. Ancient documents say that Dayuan is the birthplace of Ferghana horses, one of China’s earliest imports from the state, famed for their speed, toughness, and endurance.

That year, Wang invited scholars from the three countries to Xi’an for a seminar to discuss archaeological work in the Fergana Valley, which led to an agreement on future multilateral cooperation.

In September 2019, the first joint archaeological exploration and academic exchange activities regarding the valley were held in Kyrgyzstan, and a second round was held in Uzbekistan last year.

The sessions were essential because they not only helped resolve academic issues but also promoted people-to-people connectivity.

During the second event, Abdulkhamidjon Anarbaev, an archaeologist from Uzbekistan met an old classmate, Bakyt Amanbaeva, an archaeologist from Kyrgyzstan, by accident.

“They were classmates as they pursued doctorates in the former Soviet Union in the 1970s,” Wang said. “They hadn’t met each other for three decades. They cried on each other’s shoulders when they met again. It was deeply touching.”

Wang said that the Chinese and foreign archaeologists pay attention to respecting each other, and to promoting mutual understanding, while working in Central Asia. They highlight the protection of the sites once they are excavated, and the need to refill them when the excavation ends.

In 2019, while his teammates were excavating the Serkharakat Site in Uzbekistan, they discovered that a bulldozer from a nearby brickyard had accidentally dug up some buried artifacts.

Anxious about any further destruction of the then-unknown site, Wang and his colleague Muttalib Hasanov, a researcher at the Institute of Archaeology, Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, stood in front of the bulldozer to force the driver to stop and immediately contacted cultural heritage officials.

As a result of their efforts, the brickyard suspended work to make way for excavations, leading to the discovery of the Chinar-Tepa Site, an important site dating from the Kushan Empire (1st-4th century), which contained the remains of a small city and tombs that were excavated this year.

Tang Yunpeng, a member of Wang’s team, also highlights their friendship with locals when they work in Central Asia. He cites the example of Djasur Navbatov, a driver from Uzbekistan who has worked with them every year since 2017.

“Since we often work in remote areas with inconvenient transportation, we always rent his car for months at a time. He often offers us help, like allowing us to deposit our goods and materials at his home or providing us with tools. We have celebrated each other’s birthdays, and he has learned some Chinese and even some archaeological techniques from us,” Tang said.

He said that some issues are a matter of scholarly debate. For example, China has different research methods for stratigraphy (the study of layers and sediments) and typology from those of Central Asian countries.

At first, Central Asian colleagues had doubts about using the Luoyang Shovel (a curved spade Chinese archaeologists use to identify soil structure) but after fieldwork proved the effectiveness of this method, they gradually accepted it.

Northwest University has also trained young scholars from Central Asian countries, such as Bahodir Yusufov, a student from Uzbekistan currently pursuing his doctorate in archaeology at Northwest University, who is also a member of Wang’s team.

Yusufov started as a history major and was later introduced to the team by an undergraduate classmate.

He was impressed by the story of a man from his hometown, told to him by a researcher at the university. The man, known as Wirkak (or Shi Jun in Chinese), was a Sogdian trader who traveled along the Silk Road to Chang’an during the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-581). When Wirkak died, he was buried in Chang’an. In 2003, his tomb was rediscovered and excavated, yielding discoveries of precious artifacts that suggested elements of cultural exchange.

“I have not only learned archaeology at the university but also learned things related to my hometown,” Yusufov said.

He took part in the archaeological surveys in the Surkhandarya Basin last year and worked with Tang.

“At the beginning of our collaboration, we maintained a cautious attitude. However, after close, long-term fieldwork, our friendship developed over time,” Tang said. “This bond has actually grown in the field, and was not the result of a single meeting or discussion.”

In the 1930s, pioneering archaeologists from Northwest University, such as Huang Wenbi, began researching the Silk Road by excavating Zhang Qian’s tomb in Shaanxi and doing some fundamental research in Xinjiang.

Almost a century later, operating on a wider international horizon, archaeologists have greater expectations.

“Our research on the Silk Road today is deeply rooted in generations of predecessors,” said Sun Qingwei, president of Northwest University and an archaeologist. “There were many difficulties. However, the bravery of scholars and continuous exploration have led to fruitful discoveries.

“Over the years, our university’s archaeological team has been conducting archaeological work in Central Asia,” Sun said. “They have truly lived and worked together with Central Asian scholars and people.

“This kind of integration and mutual exchange of knowledge has played a particularly effective role in advancing communication and mutual understanding between us archaeologists and countries along the Silk Road,” he added.

“Through archaeology, we can better tell the stories of the Silk Road, and contribute to building a community with a shared future for mankind.”

Qin Feng in Xi’an contributed to this story.

Contact the writers at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn