Once endangered across the country, region increases the number of newly built wooden arch structures, outstripping the old, Wang Ru reports.

When heritage activists met Dong Zhiji in 2003, whose name they'd found on a bridge built decades earlier, he was 78 years old. By then, building bridges was a distant memory, something he'd done in a previous life. But the conservators were relieved, as they'd finally found someone who still had the skills to build the endangered structures.

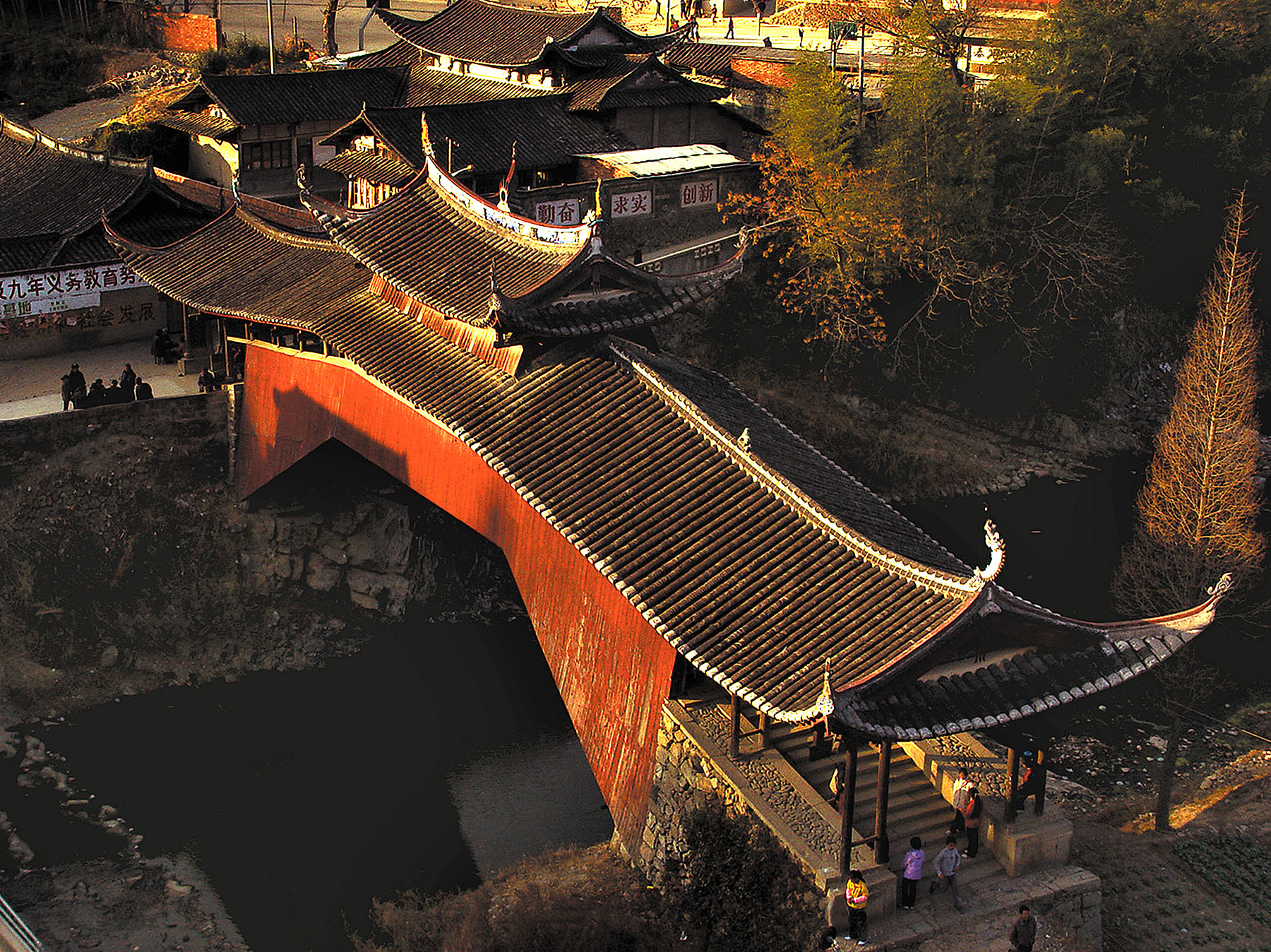

Wooden arch bridges were once widespread in the mountains of what is now southern Zhejiang and northern Fujian provinces, but since the 1960s, they have gradually been replaced by concrete and steel, leading the craftspeople who made them to turn to other professions. By the turn of the millennium, when they regained their cachet, those able to build the bridges seemed to have vanished.

READ MORE: Connecting the past with the future

That's why finding Dong was an amazing feat. Although he last built a bridge about 60 years ago, he still remembered the techniques, and in 2004, he had the chance to practice those skills on the Tongle Bridge, and train several apprentices in the process.

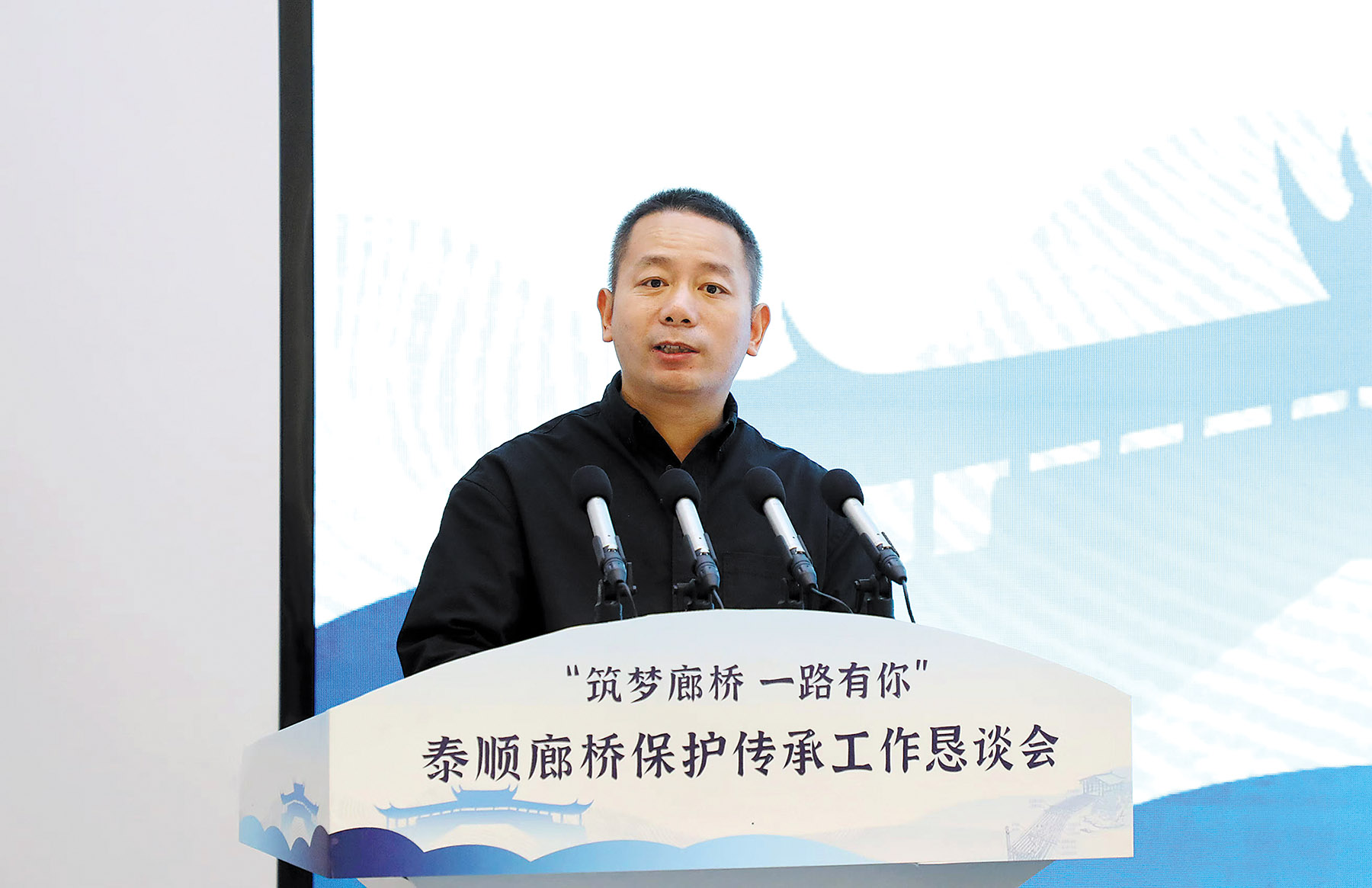

Zhong Xiaobo, director of the Wenzhou Covered Bridge Culture Society, helped build the Tongle Bridge. He has devoted over two decades to protecting wooden arch bridges, and says Dong's knowledge on wooden arch bridges has made the revival of the then-endangered craft possible.

On Dec 15, the traditional design and practices for building Chinese wooden arch bridges, listed in 2009 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, was transferred to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, marking its remarkable revival.

Zhong was overwhelmed by the news. "This is a reward for our efforts in protecting the bridges and passing on skills. It was a long, arduous journey, from no craftsman to one, from one to many. Finally we see the first rays of dawn."

Protective efforts

Born in Taishun county in Wenzhou, Zhejiang, in 1977, Zhong never thought of wooden arch bridges as special — they were something he saw every day as an adolescent.

It was only as he pursued a bachelor's degree in Chinese language at Chengdu's Southwest Minzu University in Sichuan province in 2000 that he discovered their value. He was shocked to find that something he'd taken for granted was actually precious heritage, prey to fire, flood and insects, and that the skills to make them were in danger of becoming lost.

Since then, he has devoted his time to encouraging efforts to protect them.

Zhong says that there are few wooden arch bridges in China, and most are found in the seven mountainous counties in southern Zhejiang and northern Fujian. They use short, interlocking logs to create long arches without nails or rivets, a design that efficiently spreads the load, often without the help of pillars. Originally, the skills to make them would be passed down within families, or through apprenticeship.

Besides carrying traffic, they were social hubs where people gathered to chat, relax, or make religious offerings.

In 2000, Zhong launched a website about the bridges, drawing the attention of fans. A few years later, he held photo exhibitions in universities in Zhejiang and Shanghai to promote them further.

In 2003, he heard of plans for a hydroelectric power station upstream of the Santiao Bridge, which would cut the flow under the Tang Dynasty (618-907) bridge. Worried that the lack of water would render the bridge useless, causing it to fall into obscurity, he issued a call to action on his website.

With public efforts, the power station builders made a concession on the flow to allow the bridge to continue to fulfill its ancient duty.

"Decades later, this is still vivid in my heart. Saving the bridge gave us experience and confidence, and raised awareness of the need to preserve them," he says.

Cultivation of inheritors

Soon after, he set up the Wenzhou Covered Bridge Culture Society and organized seminars. He also encouraged scholars to check on them every year. Thanks to his hard work, wooden arch bridges went from being nestled in deep mountains to becoming known to the world.

"Over the past two decades, Zhong has devoted a significant part of his spare time to protecting the bridges. … His stories reveal that these structures are not merely about transportation but are vessels of culture and testimonies of history. They are invaluable treasures; and the duty of preserving them and promoting their cultural significance should be embraced by every individual," says Wang Jianghui, a student at the Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics who participated in one of Zhong's activities last year.

As a result of the publicity, Zhong says awareness of protecting the bridges has improved greatly. "In the past, they were left without protection and often had to give way to development. But now we have teams of volunteers and devices to monitor threats and take measures to eradicate them."

He has also seen the growing number of bridge makers, who help ensure their continued existence.

Since Dong and a few other elderly craftspeople were found, the local government has adopted measures, like subsidies for constructing bridges using traditional skills, to encourage the use and spread of the craft.

"Now, the number of new wooden arch bridges in some parts of southern Zhejiang and northern Fujian exceeds the old, a positive trend in development. Given that just two decades ago they were endangered, we can confidently say that the situation has undergone a welcome transformation," Zhong says.

According to official documentation about the craft on the UNESCO website, when it was inscribed on the Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding list in 2009, there were only four people with mastery of the core techniques, all over 75. Now there are more than 40 representative inheritors, aged 56 on average.

For Zhong, the most remarkable testimony to such efforts was the restoration of three old bridges in Taishun, which are protected at the national level, after super typhoon Meranti almost washed them away in 2016.

In less than a year, 90 percent of their wooden components had been retrieved, and the three bridges had been restored by inheritors, many of whom were Dong's students.

"The restoration was accomplished in a short time, validating efforts in preserving and passing down the traditional craft," says Zhong.

ALSO READ: Bridging the gap between now and then

He and his counterparts have also helped bring the bridges onto the global stage.

In 2013, he participated in a seminar about the protection of covered bridges in the United States, and exchanged experiences with his US counterparts.

"Although different in style, the US also boasts a large number of covered bridges and their experience in protecting them can be inspiring for us," he says.

Zhong and his colleagues have built traditional Chinese bridges abroad and have sent models as gifts, introducing their design and the knowledge embodied in their making.

"Wooden arch bridges have a special meaning for someone like me who has grown up by their side. Who doesn't take pride in the beauty of where they are from? It's really meaningful to do something for the treasures of my hometown," he says.

Contact the writer at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn