Forbidden City event looks at how a small plot of land can inspire and nurture human creativity, Wang Kaihao reports.

In 1772, Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), then just turning 60, had reason to be joyful after finally securing his dream place for retirement in the Forbidden City, the royal palace in the heart of Beijing.

Known as Qianlong Garden, the site in the Ningshou Gong ("palace of tranquility and longevity") compound was designed in a breathtakingly exquisite way.

Pavilions, corridors, rockeries, a belvedere, a teahouse, a Buddhist hall and more subtle settings provided a retreat amid mountains and forests within the merely 6,000-square-meter space, all with a touch of splendor.

READ MORE: National Museum springs into season

Nevertheless, the emperor had little time to appreciate his surroundings as he gave the throne to his son when he was 85. He merely enjoyed three years of "retirement" before he died.

We may hardly know whether Qianlong had enough time to fully savor the retreat from everyday cacophony, but the garden has left us a poetic legacy: a coming together of aesthetics and nature. This is undoubtedly an inspiration for visitors to a new exhibition in the Forbidden City, now known as the Palace Museum.

For the occasion, Rejoicing in Woods and Springs: A Journey through Garden Cultures in China and the Wider World, which will run through to June 29, more than 200 exhibits from home and abroad, including landscape paintings, sculptures, furniture and indoor decorations, are on show at the Meridian Gate Galleries.

In this exhibition, visitors can appreciate various artworks related to gardens, not only those famous throughout Chinese history that reveal Zen and literati's refined taste, but also different styles across the world, including the villa garden of Pompeii in Italy, medieval monastery gardens, the Palace of Versailles in France and gardens from the Edo period in Japan.

Qianlong Garden is where to start the journey.

"It almost encompasses all the aesthetic interests of ancient Chinese garden-making," says Li Yue, the chief researcher on the Qianlong Garden project from the Palace Museum's department of architectural heritage.

"As we review the Qianlong Garden, it is not merely out of curiosity about an emperor's aesthetic taste, but also because it provides us with a thought-provoking perspective that is still inspiring: Is there another, more delicate, more serene, and more poetic way for humans to interact with nature and space?"

Resonance in space

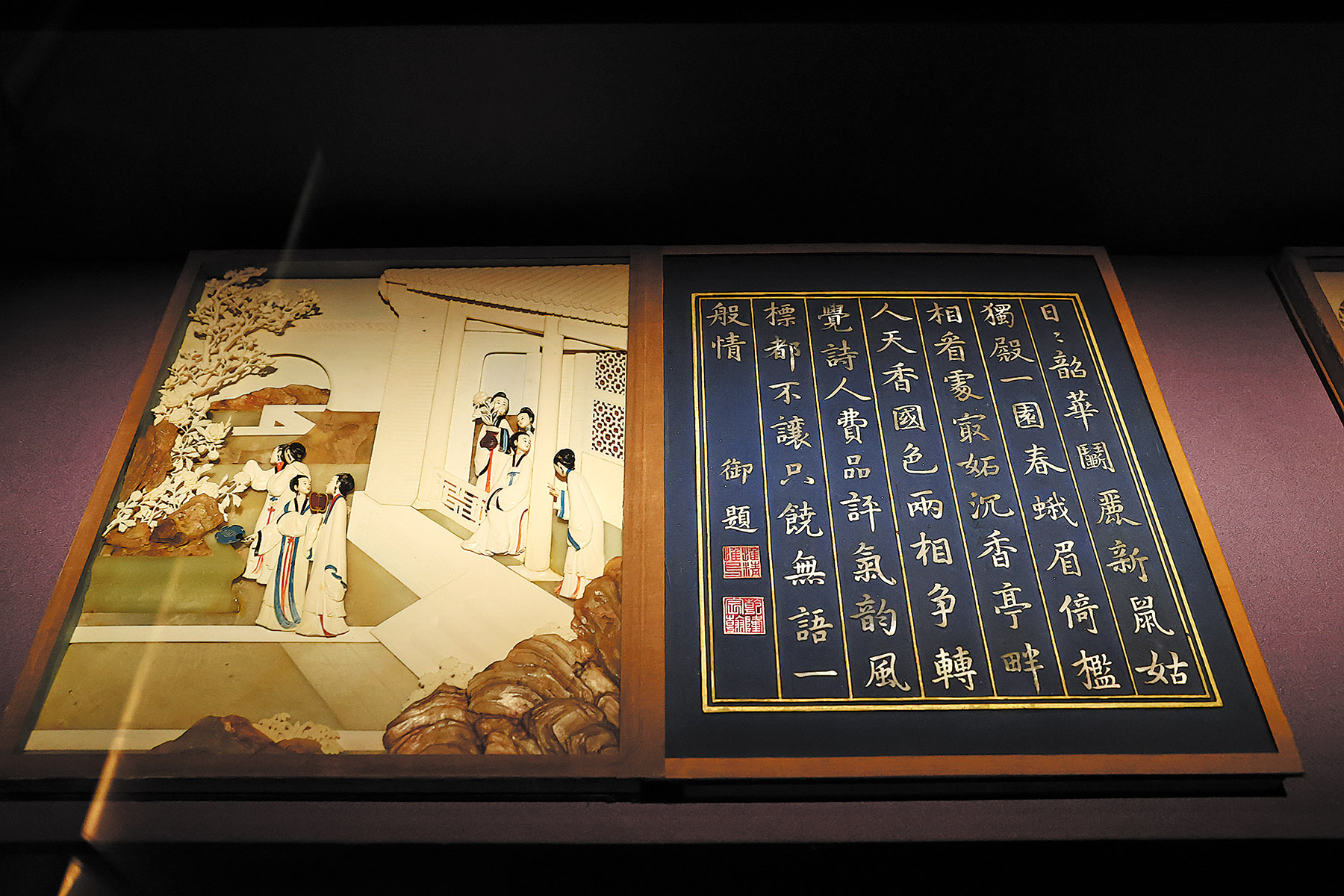

The wooden gate carved with lotus patterns from the Building of Luminous Clouds (Yunguang Lou), the Buddhist hall in the Qianlong Garden, is a highlighted setting in the exhibition.

Through the gate, visitors may peep into a group of wooden screens depicting Buddhist deities, also from that hall, and nurture a contemplative moment like the retired emperor.

A pair of jade censers further create an atmosphere of tranquility. They are from the Hall of Imperial Peace (Qin'an Dian), a Taoist temple in the Imperial Garden in the north of Forbidden City.

Cloisters in a Nunnery, a German watercolor on loan from The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, will also catch the eye. The artist, Simon Quaglio, used light and shadow to highlight the elegant arches and exquisite columns within the garden of nunnery that also represents the strength of belief.

"When we designed this exhibition to put Chinese and overseas gardens together, it would be too abstract if we just display their typical elements and thus theoretically analyze their respective features," explains Zhu Yufan, a professor at Tsinghua University and a co-curator of the exhibition.

"Everybody would have certain activities in the gardens," he says.

"It would be easier for visitors to feel emotionally connected if we tell them what happen in the gardens and thus reflect the garden owners' thinking."

Recreation, antique collection, mental cultivation, celebrities gathering and other activities in the garden thus compose different themes of the exhibition.

Chemistry may naturally be created in this arrangement.

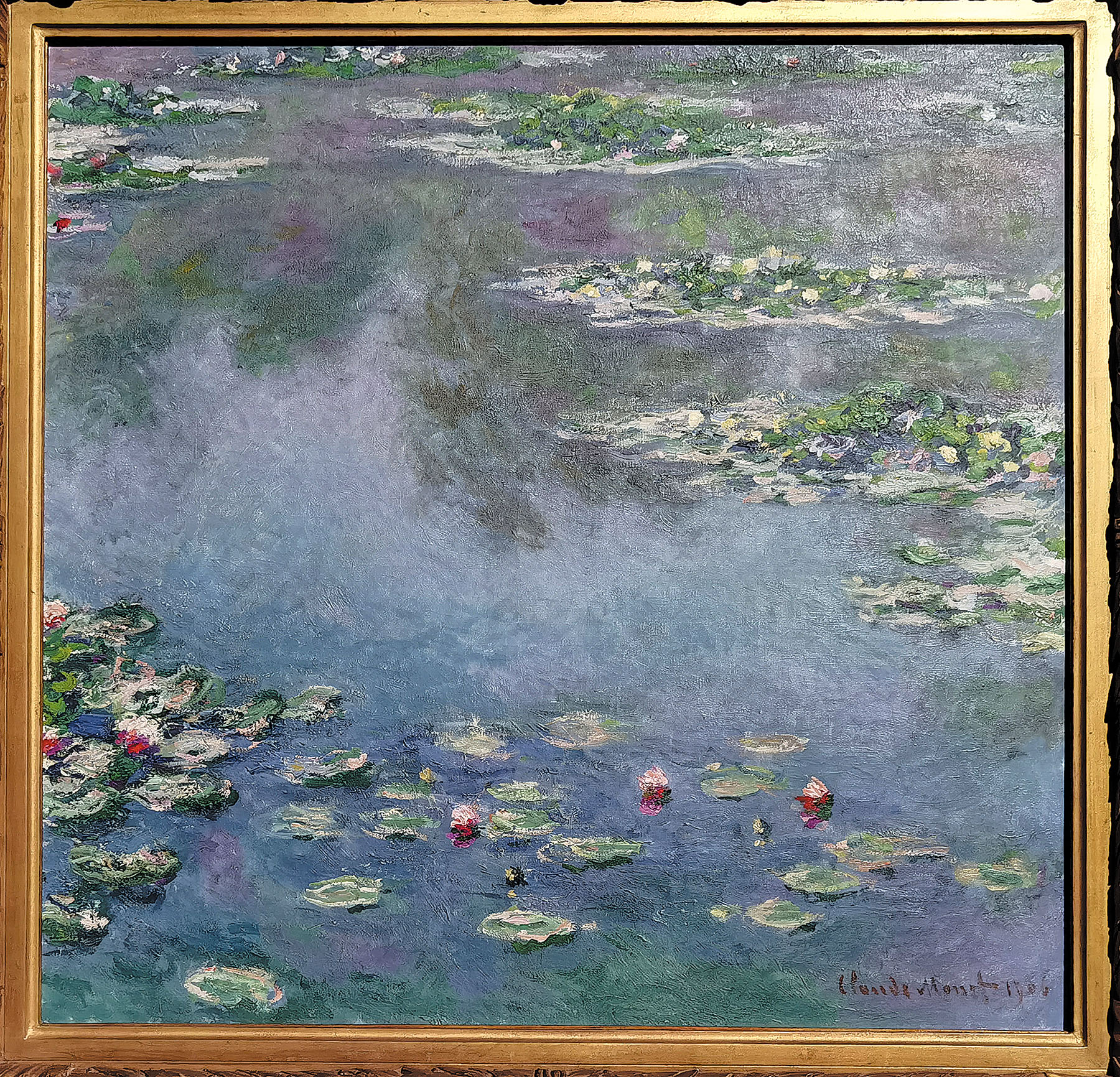

Walking along the zigzag lane in the gallery, which mimics the shape of bridge in a traditional Chinese garden, visitors can find Claude Monet's Water Lilies on one side.

In 1906, the French art icon was mesmerized sitting by the pond in his own garden, making this moment immortal through his brush.

Across the lane, the Japanese ukiyo-e master Katsushika Hokusai's color woodblock print Iris and Grasshopper (1833-34) may explain his ideal garden and how his worship of nature influenced Monet and French impressionism. Both art pieces are from a collection at the Art Institute of Chicago.

An exhibited Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) rockery stone, named "cloud-embracing", reveals a favorite element in Chinese gardens; a bronze statuette Neptune with a Dolphin stands a few meters away. Once set atop a fountain in a villa of Rome, the statuette was made after Lorenzo Bernini's model and also provides an intriguing glimpse of a classical Italian garden.

"This initiative aims to integrate elements of literature, drama and historical allusions with landscape design, anchoring itself in Chinese classical gardens while embracing global garden cultures," says Wang Yuegong, deputy director of the Palace Museum.

"It initiates a dialogue that showcases the artistic splendor of Eastern and Western horticultural traditions, ultimately unveiling the humanistic philosophies embedded within these living masterpieces."

Through the artworks, the metaphysical thinking surrounding gardens may still resonate among modern viewers.

Soulful exploration

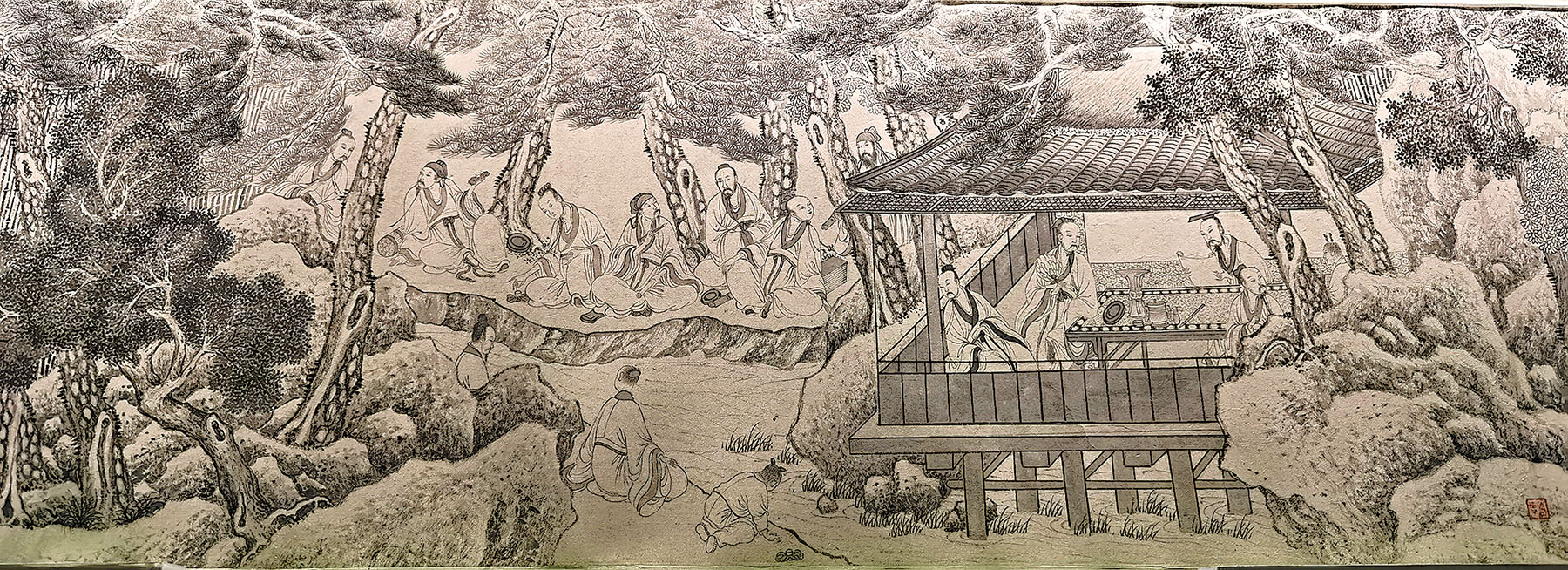

On a bright spring day in 353, a group of Chinese literati gathered in the Orchid Pavilion for a ritualistic cleansing ceremony known as xiuxi, often involving bathing, meditation and reflection.

They dedicated their poems to the harmony of nature and grandeur of the universe, and Wang Xizhi then created the calligraphic work Preface to the Orchid Pavilion, a monument in Chinese art history, also an everlasting classic of literature.

Literati throughout Chinese history tried to duplicate Wang's ultimately refreshing moment in their gardens.

In Xiuxi, an exhibited Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) painting, people are seen to hold the purification ritual by water to ward off misfortune. On another Ming painting Jade Grotto Immortal Residence, the artist incorporates a grotto, a symbol of the realm of paradise, in the garden to reveal a pursuit for reclusive living.

In Qianlong Garden, the emperor also ordered the construction of a pavilion to pay homage to that gathering in 353.

"The gathering deeply influenced a guiding mindset of gardening in China," Zhu explains.

"People want to highlight the spirits represented by the natural landscape, in which they can nurture their virtue. Through designing, they reconstruct relations between humans and the landscape."

Such philosophical inspiration can also be seen in Western gardening.

An engraving by Albrecht Duerer in 1497 and a drypoint by Rembrandt in 1653, both on loan from Chicago, shared a theme focusing on a key theologian of early Christianity, Saint Jerome.

Contemporaneous with Wang Xizhi, the theologian is often portrayed either as a hermit engaged in ascetic practices in the wilderness, or as a scholar engaged in self-reflection. His image influenced the development of European garden art from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance and beyond, according to Zhu.

"Gardening is to explore an ideal habitat for souls," he says.

Fruitful interaction

In the world of gardening, the East and the West are not two separate chapters. Their interaction also led to extraordinary fruits, as the exhibition reminds us.

The copperplate engraving of the album of the Old Summer Palace shows how designers absorbed Baroque art and created the famous Grand Fountains and Western Mansion area in the Qing royal resort.

While a 1762 oil on canvas, Kew Gardens: The Pagoda and Bridge, offers a slice to see Chinese inspiration in British gardening, similar cases happened in Versailles, France, following Louis XIV's admiration for Chinese art.

Elisabeth Maisonnier, chief curator of heritage at the National Museum of the Palaces of Versailles and Trianon, says: "The influence of Chinese gardens was important, mediated by European visitors who brought back descriptions or sent paintings, especially of the gardens of the Forbidden City, where pagodas, pavilions, temples and Chinese houses can be found."

She continues: "The very design of Chinese gardens, miniature worlds where mountains and rivers are essential … conceived as places of retreat and meditation, or pleasure and feasting for the close friends of the owner."

ALSO READ: Jade's royal seal of approval

This year marks the centennial anniversary of the founding of the Palace Museum in the former imperial palace of China. In the name of gardens, the exhibition per se also seems to display the museum's international horizon and a bond for cross-border cultural exchange on the key occasion. About 70 exhibits come from overseas institutions.

"Museums offer us similar opportunities (like gardens) to bring objects from diverse cultures and civilizations together and spur a new, evolving vision of our world," says James Rondeau, president of the Art Institute of Chicago.

"I hope these seeds of exchange we plant today, through our joint efforts, would continue to blossom."

Stepping out of the galleries, people may understand what the exhibition curators really want to convey through the poster.

There, a group of Chinese literati from Xiuxi walks on the wooden arch bridge that spans across Monet's pond full of water lilies.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn