Ongoing exhibition celebrates the calligraphy of noted 20th-century artist and pioneer Liu Haisu, Lin Qi reports.

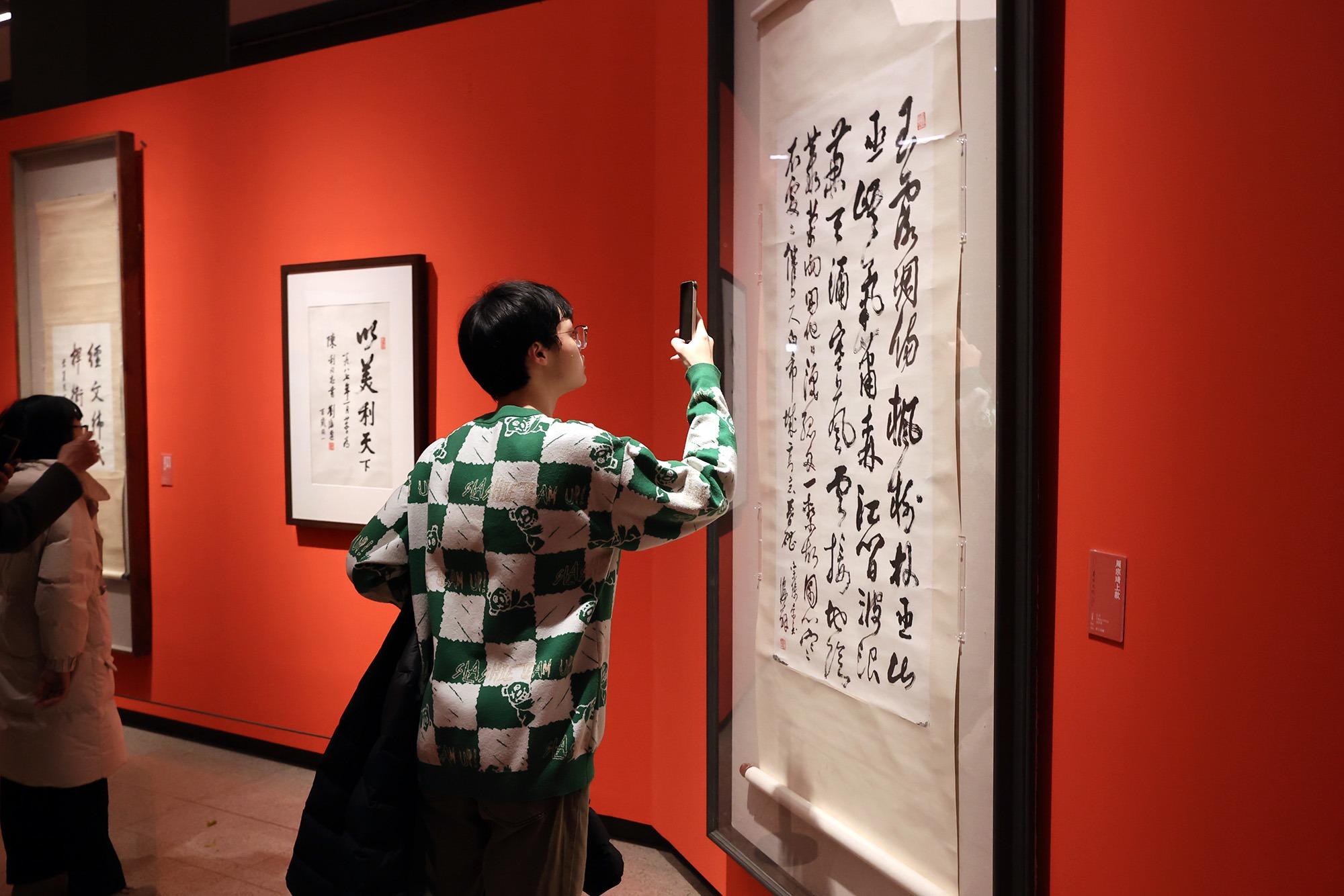

A visitor takes photos of an exhibit at the Rhythmic and Vivid Ink exhibition that spotlights modern art master Liu's accomplishments in calligraphy. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

A visitor takes photos of an exhibit at the Rhythmic and Vivid Ink exhibition that spotlights modern art master Liu's accomplishments in calligraphy. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

Liu Haisu, one of the most prominent artists of 20th-century China, is held in high esteem for leaving an oeuvre of paintings that connects the aesthetic and cultural spirits of both the East and the West. His experimental approach to Chinese painting reformed the look of this art style, which demanded innovation at the turn of the 20th century.

He contributed greatly to the establishment of modern art education in his home country. In 1912, he cofounded China's first school of fine arts in Shanghai and became its deputy headmaster. He was just 17 at the time.

In between these characters and lines, one can see the literary accumulations, morality, experiences and personality of my father.

Liu Chan, Liu Haisu’s daughter

Fine examples of Liu's work can be found in the collections of major museums, both at home and abroad, including the National Art Museum of China, which mounted four carefully curated exhibitions of his art between 1979 and 2017. Now a fifth show dedicated to the artist is currently underway, and for the first time, it is fully dedicated to the calligraphy that Liu created with imagination, perseverance and a firm belief in the cultural tradition of his homeland.

Titled Rhythmic and Vivid Ink, the exhibition runs until Monday and has, so far, received rave reviews, not just because it has directed the spotlight specifically to Liu's accomplishments in calligraphy, an area not widely known to the public compared to his paintings, which are marked by their majestic mood and highly saturated colors. The calligraphy on show reveals Liu's true temperament, as well as his views on life, art and the world.

The exhibition brings together 150 pieces of calligraphy from several museums and private collectors. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

The exhibition brings together 150 pieces of calligraphy from several museums and private collectors. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

The exhibition brings together 150 pieces from several public organizations, including the Nanjing University of the Arts, which Liu headed for years, the Liu Haisu Art Museum in Shanghai, where he lived the last years of his life, and the Liu Haisu Art Museum in Changzhou, the city in Jiangsu province where the artist was brought up.

At the opening, one of his daughters, Liu Chan, donated to the NAMOC some 20 of her father's works of calligraphy from different stages of his career.

"In between these characters and lines, one can see the literary accumulations, morality, experiences and personality of my father," Liu Chan says.

"He was a man who respected our tradition and who wanted to protect it by breaking new ground," she adds. "He felt an infinite power while creating that came from Chinese civilization and spirit."

She says her father believed that the true value of art was in its being shared and appreciated by as many people as possible. In a grand gesture demonstrating this philosophy, he donated his work and collections to spread and preserve Chinese culture.

The exhibition brings together 150 pieces of calligraphy from several museums and private collectors. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

The exhibition brings together 150 pieces of calligraphy from several museums and private collectors. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

At the exhibition, there are formal examples written in various scripts and of various sizes, and there are also pieces for private use, such as letters, drafts, notes and other kinds of manuscripts, which offer a glimpse into his extensive interest and social life.

Liu Haisu's calligraphic mastery was achieved through years of practice and thorough study of Chinese characters of different kinds, including those on oracle bones, archaic bronzes, primitive stone drums and rocks and stones.

Liu Chan mentions that a highlight of the show is the juxtaposition of several pieces featuring her father's motto — jingshen wangu, qijie qianzai, literally, "long last the noble spirit and integrity" — made at different periods of time. She says the motto mattered a lot to her father and encouraged him quite often during his lifetime.

"He liked to write it, he wrote it again and again," Liu Chan says. "He said all arts were created out of one's noble spirit, and those who made art should also be of high morality."

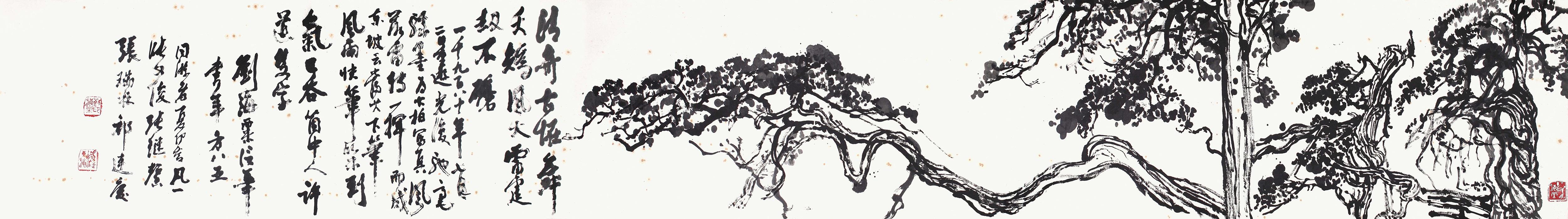

Landscape with Calligraphy by Liu Haisu. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

Landscape with Calligraphy by Liu Haisu. (JIANG DONG / CHINA DAILY)

Liu Haisu learned calligraphy in childhood, before he even learned to draw. Later, in Shanghai, he was introduced to Kang Youwei, a renowned reformist scholar and calligrapher, under whose discipline he improved greatly in both calligraphy and poetry.

"Liu's calligraphy is rhythmic and has the beauty of structure. He integrated the many scripts he practiced to create a new, distinctive style," says Wu Weishan, director of the NAMOC.

He says that while the formal works deliver majesty, the poems and letters Liu Haisu wrote show the delicate feelings and innocence in his character, and his strokes show a poetic sensibility and a painterly beauty, as forcefully as the way a dragon makes waves in the sea, and "which have generated a sound, deep resonance in people's hearts".

Contact the writer at linqi@chinadaily.com.cn