In the first article of a series on how non-fungible tokens have captured the popular imagination — entering all possible areas of art, entertainment and leisure — Joyce Yip looks at how the major auction houses are reshaping the NFT landscape.

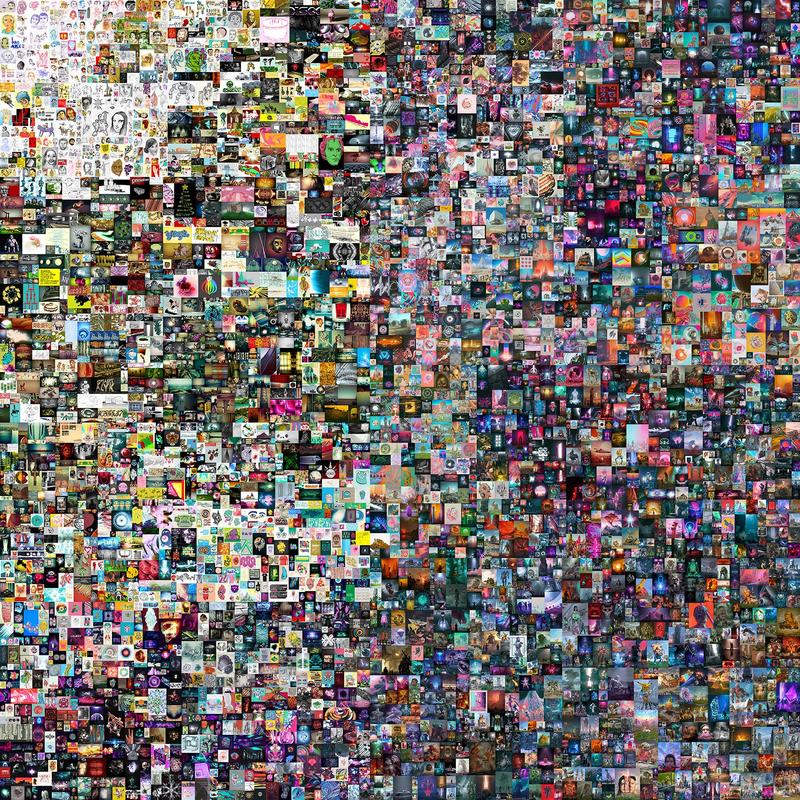

A section of Everydays: The First 5,000 Days. The digital mosaic is composed of 5,000 images that Beeple released online, one a day, starting in May 2007. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A section of Everydays: The First 5,000 Days. The digital mosaic is composed of 5,000 images that Beeple released online, one a day, starting in May 2007. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

On March 11, 2021, the world was stunned to learn of the $69.4-million sale of digital artist Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5,000 Days, at a Christie’s auction. Everydays is an example of NFT art, and the astronomical sum it achieved prompted the term to enter everyday lexicon. An NFT — or non-fungible token — is a noninterchangeable data unit authenticated by blockchain, with the majority stored on the Ethereum chain. In the art world, this means a digital asset, which may or may not be linked to a real-world object, but either way is appreciated — as are all the finest works of art — for its provenance and uniqueness.

Three months after Everydays made headlines, Sotheby’s achieved the highest price to date for an exemplar from CryptoPunks — the first profile picture (PFP) NFT series, minted in 2017 — when #7523 sold for a cool $11.8 million (that price was dwarfed in February by the sale of #5822 for $23.6 million, via developer Larva Labs’ online marketplace). PFPs are avatars prized for their unique characteristics — and #7523, dubbed “COVID Alien”, is the only Punk with a surgical mask.

The art itself may appear insignificant by traditional standards, but NFT collectibles are highly liquid, and often leverage off the blockchain with promises of utilities such as games, tangible giveaways, and a sense of community among the owners. For instance, owners of the PFP project Private Jet Pyjama Party, by London artist Benny Robinson, get an actual set of pajamas, discounts at high-end fashion brands and cyber access to weekly poker nights.

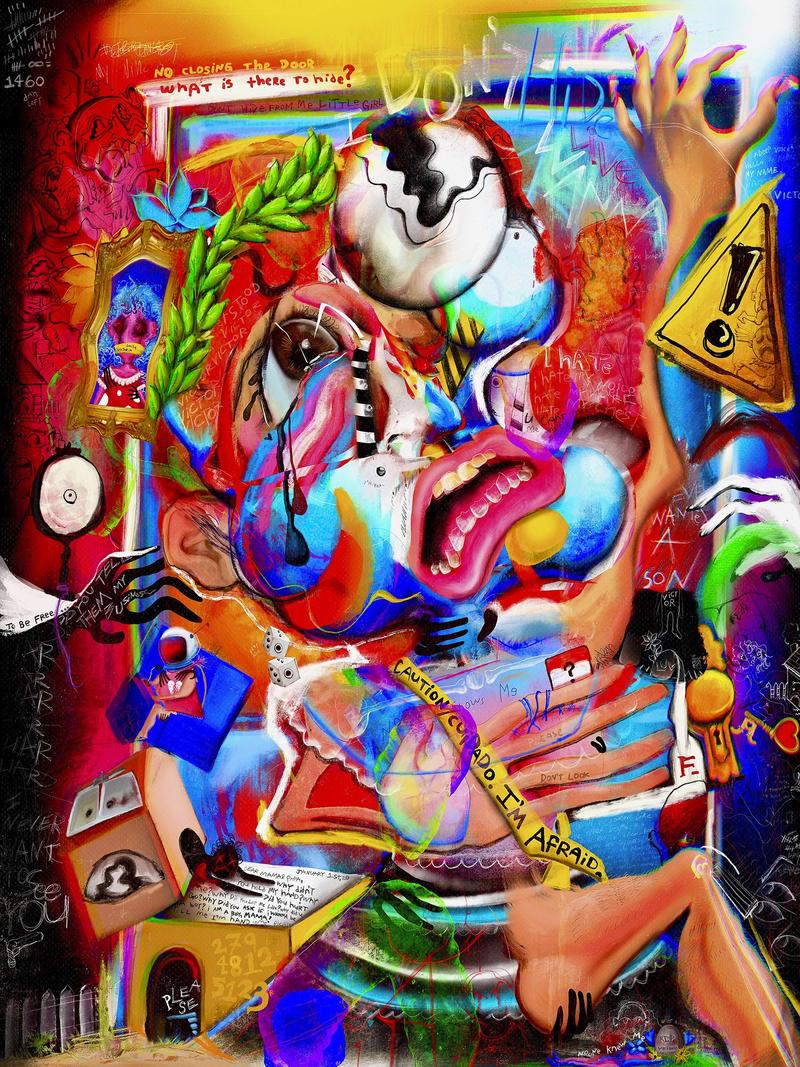

Year 1, Age 14 — It Hurts to Hide, Lot 1 of 5 from Hello, i’m Victor (FEWOCiOUS) and This Is My Life. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Year 1, Age 14 — It Hurts to Hide, Lot 1 of 5 from Hello, i’m Victor (FEWOCiOUS) and This Is My Life. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Highs and lows

Both digital artists and PFP project owners are benefiting from the reputation of famous auction houses that have endorsed them, while the houses themselves are welcoming NFT buyers with open arms — the crypto collectibles having helped them to a bumper 2021. The speculative nature of NFTs is also right up the alley of many contemporary art collectors.

According to the Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2021, an estimated $3.5 billion was spent on NFT art and collectibles in just the first nine months of last year. In the months since, noted NFTs have run the gamut from crusading to frothy. At the serious end, Clock, by the anonymous digital artist Pak, displays the number of days Julian Assange has been in jail; the $52.8 million raised by its sale in February will go toward the WikiLeaks founder’s legal fees. At the opposite end of the spectrum, a piece from Melania Trump’s POTUS NFT Collection, depicting her husband’s time in office, costs just $50; while in January, Paris Hilton gifted an NFT photo collage of herself and her husband on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon to the host and everyone in the audience.

The $3.4 million Bored Ape Yacht Club #8817 is the most expensive in the collection to date in part because of its gold fur. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The $3.4 million Bored Ape Yacht Club #8817 is the most expensive in the collection to date in part because of its gold fur. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Coming-out party

NFTs have had a relatively limited impact on the major auction houses’ bottom line, despite the surging popularity. All together, Sotheby’s and Christie’s sold $250 million in NFTs in 2021, against a gross revenue of $14.4 billion. But competitive the houses must remain in a growing market with new players aplenty, while continuing to prove their worth as middlemen for a commodity designed for decentralized trade.

Following Everydays, Christie’s Pride program in June saw five NFTs by 18-year-old transgender artist FEWOCiOUS fetch a total of $2.2 million. In November, another Beeple piece, Human One, sold for $28.9 million. And in December, at Art Basel Miami, Christie’s hosted its first on-chain auction — meaning that the winning bids were executed by smart contracts — on the leading NFT platform OpenSea.

Before the bidding, lots were exhibited as part of The Gateway, a multisensory experience blending music and art. Highlights included work by Mad Dog Jones, who became the most expensive living Canadian artist after his Replicator sold at the auction house Phillips for $4.1 million in April last year; as well as a PFP collection of CyberKongz pixelated gorillas. The event brought in $3.6 million — not especially impressive considering another of the house’s PFP sales had closed at more than four times that amount a few months prior.

Forever by Mad Dog Jones was among the highlights of the first-ever on-chain NFT auction, a December 2021 collaboration between Christie’s and the leading NFT marketplace OpenSea. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Forever by Mad Dog Jones was among the highlights of the first-ever on-chain NFT auction, a December 2021 collaboration between Christie’s and the leading NFT marketplace OpenSea. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Bubble territory

As for the appeal of crypto art, Noah Davis, Christie’s head of digital sales, says: “I don’t know a single young person who wants the responsibility of owning a very expensive artwork — or any physical good that’s extremely precious. Young people want mobility and freedom, and physical possessions can be kind of anathema to some. NFTs (make it possible to) own something in its inherently ephemeral form. I believe this is a massive upgrade.”

Max Moore, Sotheby’s director and head of contemporary art auctions, thinks that NFT collectibles and fine art come under the same category, but notes that PFP collectors “definitely favor liquidity and high turnover”.

“This is why they’ve received so much attention — because of their ability to continue the upward trend and the hype, versus one-of-one artworks that are exchanged between a few collectors,” he adds.

September and October 2021 saw Sotheby’s involved in multiple NFT projects: partnering with Digital Art Fair Asia, held in a physical space in Hong Kong; auctioning the Bored Ape Yacht Club collection, which brought in $24.4 million; and most impressively, launching its own marketplace, Metaverse. The auction house also holds regular educational talks for its traditional clients, in an effort to differentiate NFTs from the volatile crypto world.

“There will be a correction — it’s inevitable, given the demand for and volume (of PFPs) sold, … but actual artwork is still what retains the attention,” says Moore. “The exciting thing for me is to work with the artists on a primary level. There aren’t the same restrictions as there are in traditional artwork with galleries, representation, purpose or targets.”

CyberKong #46, part of the Genesis Cyberkongz collection of 1,000 2D avatars by artist Myoo, achieved the second-highest hammer price at the Christie’s x OpenSea on-chain NFT auction. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

CyberKong #46, part of the Genesis Cyberkongz collection of 1,000 2D avatars by artist Myoo, achieved the second-highest hammer price at the Christie’s x OpenSea on-chain NFT auction. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Exclusivity reigns

Phillips held two PFP sales last month: of Edgar Plans’ Lil’ Heroes, and a tiny series by Monkey Kingdom. Paying homage to the mythical simian shapeshifter Sun Wukong, the 2,222-piece, eponymous Monkey Kingdom collection had been under the hammer at Sotheby’s a few weeks earlier. The Phillips sale, by contrast, presented just three Monkey Legends — designed to be Metaverse-ready, and fully customizable with accessories and clothing.

Benjamin Kandler, Phillips’ private sales assistant and NFT coordinator, says the auction house’s mission is to “build historically important collections”, regardless of the medium. Though the latest offerings deviate from the one-of-one crypto art the house had focused on in the past, Phillips stands out by offering PFPs not available elsewhere. Indeed, both Lil’ Heroes and the Monkey Legends lots were new to the market.

“We don’t engage with NFT projects that focus purely on the works as commodities,” says Kandler. “Phillips’ goal is to present the best in NFT art. This differentiation (between art and collectibles) is largely due to the mass production of collectibles and their intrinsic utility.”

The most expensive CryptoPunk in mid-2021 was the only one with a surgical mask, dubbed “COVID Alien”. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The most expensive CryptoPunk in mid-2021 was the only one with a surgical mask, dubbed “COVID Alien”. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

One person skeptical of auction houses playing the middleman between artist and collector is Shivani Mitra, managing director and curator of the Museum of Crypto Art — a virtual home for both big names and up-and-comers in the crypto world.

“Auction houses have effectively become lame over the last decade — at least for young people aged 14 to 30,” says Mitra. “We’re not like, ‘Oh my God, it’s a Christie’s drop!’ We’re talking about Supreme, Off-White, Kanye. So they’ve really seized on this as a moment to be stewards of a new technology without our electing them to be power brokers.”

While she gives credit to thoughtful events such as Sotheby’s Natively Digital: A Curated NFT Sale — held last June — which highlighted some of the earliest, rawest NFTs, Mitra is critical of the hypercapitalism that auction houses have loaded onto the NFT art world.

“People understand ‘NFT’ to be a word associated with some kind of paradigm shift, but (the public) still has to connect ‘NFT’ with art,” she says. “For the auction houses, it’s dollar sign, dollar sign. There’s a need for that in order to bring in more eyes, but it becomes hollow at some point. Art, power and money have always worked together — I’m not going to be unrealistic. But that doesn’t mean you can’t have good, meaningful change, like curators and collectors who want to tell the story of certain art or artists as alternatives to the system.”

Monkey Kingdom’s Monkey Legends #0, auctioned by Phillips last month. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Monkey Kingdom’s Monkey Legends #0, auctioned by Phillips last month. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Sensing synergies

Clement Lai, a digital art collector who has acquired both one-of-one pieces and PFPs since 2021, is grateful for the exposure provided by the auction houses.

“You always pay attention to what the auction houses are doing — it’s inevitable for any collector. What they’re doing in the NFT space is exactly like that with any other commodity: You have 10 paintings by an artist; one gets a great hammer price at Sotheby’s, and the rest of their artworks is jacked up,” says Lai, adding that the current environment is a win-win situation for auction houses and creators. “NFT creators get the momentum; the auction houses look cooler with this new offering — especially among 20-something collectors, who may not be interested in Picassos. So, why not?”

Notwithstanding the fact that NFTs are designed for decentralized trade — with talk of artists potentially initiating their own smart contracts on self-hosted websites for a truly democratic marketplace — Lai thinks the middlemen will always have a place in the world of crypto art.

“From an artist’s perspective, it’s nice to sell artwork without a middleman, but we can’t neglect the role of art galleries, auction houses and curators because if the work is just floating on OpenSea, no one is going to buy it. Buyers need human touch and want to hear the stories behind these works. That’s where the middleman comes in,” he says.

Mitra agrees, adding that curated marketplaces — not auction houses — are especially important for a medium that’s meant to support emerging artists.

“If you want to trade NFTs as collectibles, you can go to OpenSea; but if you want to find your niche, then these curators are essential. Auction houses don’t have the freedom to curate a niche,” she says. “Most people are looking for famous (artists) and fast (ways to make money), but there are groups of smart and high-integrity people looking at art itself who need these spaces, and those will always be relevant.”

While opinions vary, there’s no denying that auction houses have shaken the NFT landscape in major ways. As collectors continue to build their empires in this evolving sphere, prices achieved at auction will remain a benchmark. However, auction houses need to move in sync with developments in this rapidly evolving space in order to sustain the attention of an audience looking for more than just headline-grabbing sales.