A new exhibition at M+ reveals how Picasso’s works have inspired creativity, and hope, in artists from across Asia and continue to do so. Chitralekha Basu reports.

Although Guernica (1937) is not included in Picasso for Asia — A Conversation, a new exhibition that opened at M+ on March 15, its traces are obvious. Arguably the most well-known painting by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Guernica was the artist’s statement of protest against the bombing of the eponymous Spanish town in the lead-up to World War II. The painting remains a perennial source of inspiration to artists concerned about the signs of fascism in the world today. Hence a show that puts more than 60 works by Picasso in dialogue with another 130 by artists from around Asia expectedly features a number of those that refer to or resonate with Guernica, if not pay homage to it. Examples include Cubist Mother and Child (1959) by Luis Chan — which borrows both the time-tested motif of Christ lying dead in the arms of Mother Mary as well as the geometric shapes and skewed perspective characteristic of the cubist form from Guernica. There is also Tang Dixin’s Hands and Legs (2015-17), showing a jumble of interlocked human legs trying to break free from the iron grip of fists that hold them back. Though stylistically dissimilar, Tang’s painting shares a kinship with Guernica in that both embody the frenetic charge of people desperate to flee a conflict zone for dear life.

READ MORE: Of birds, beasts and muses

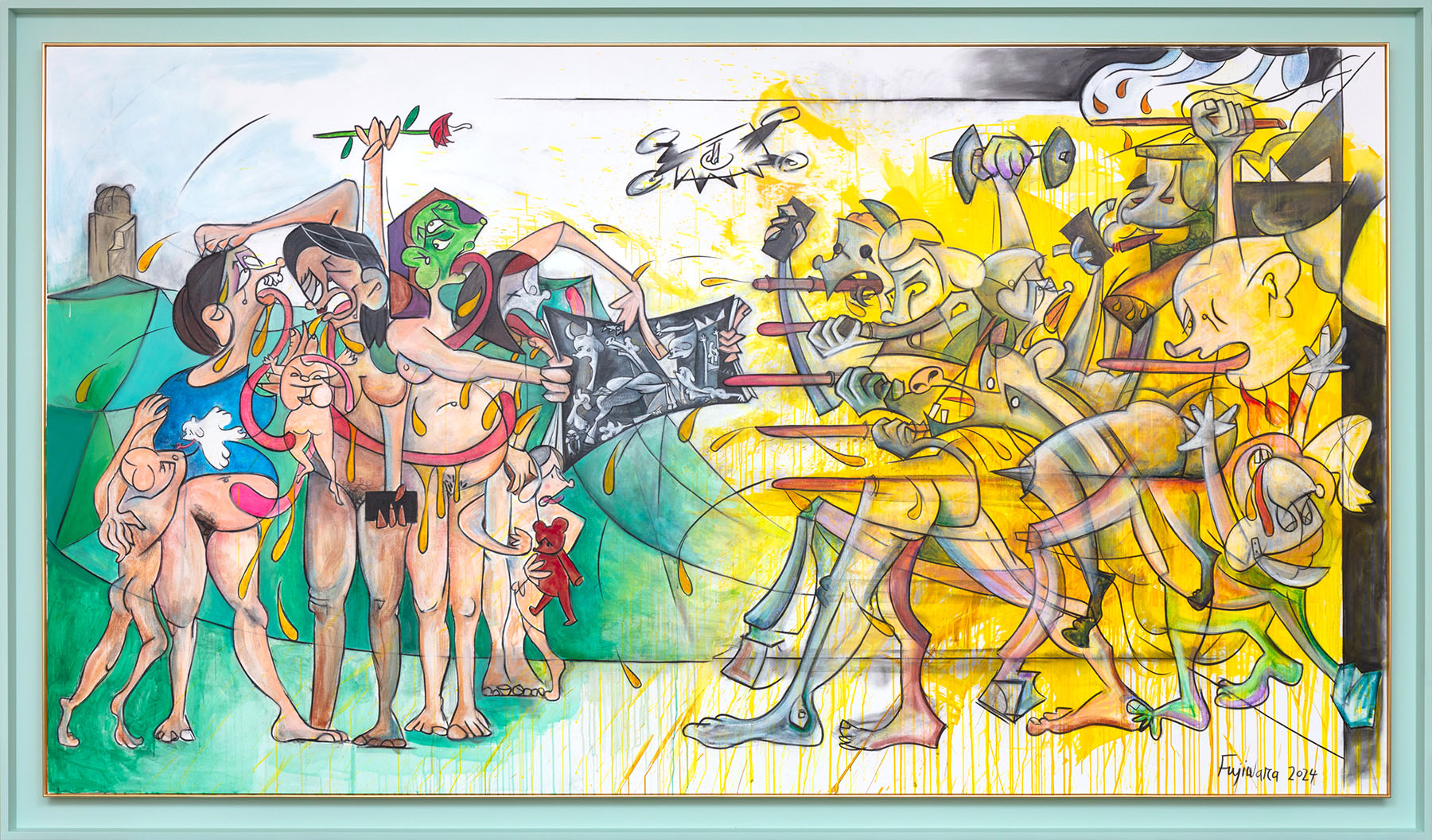

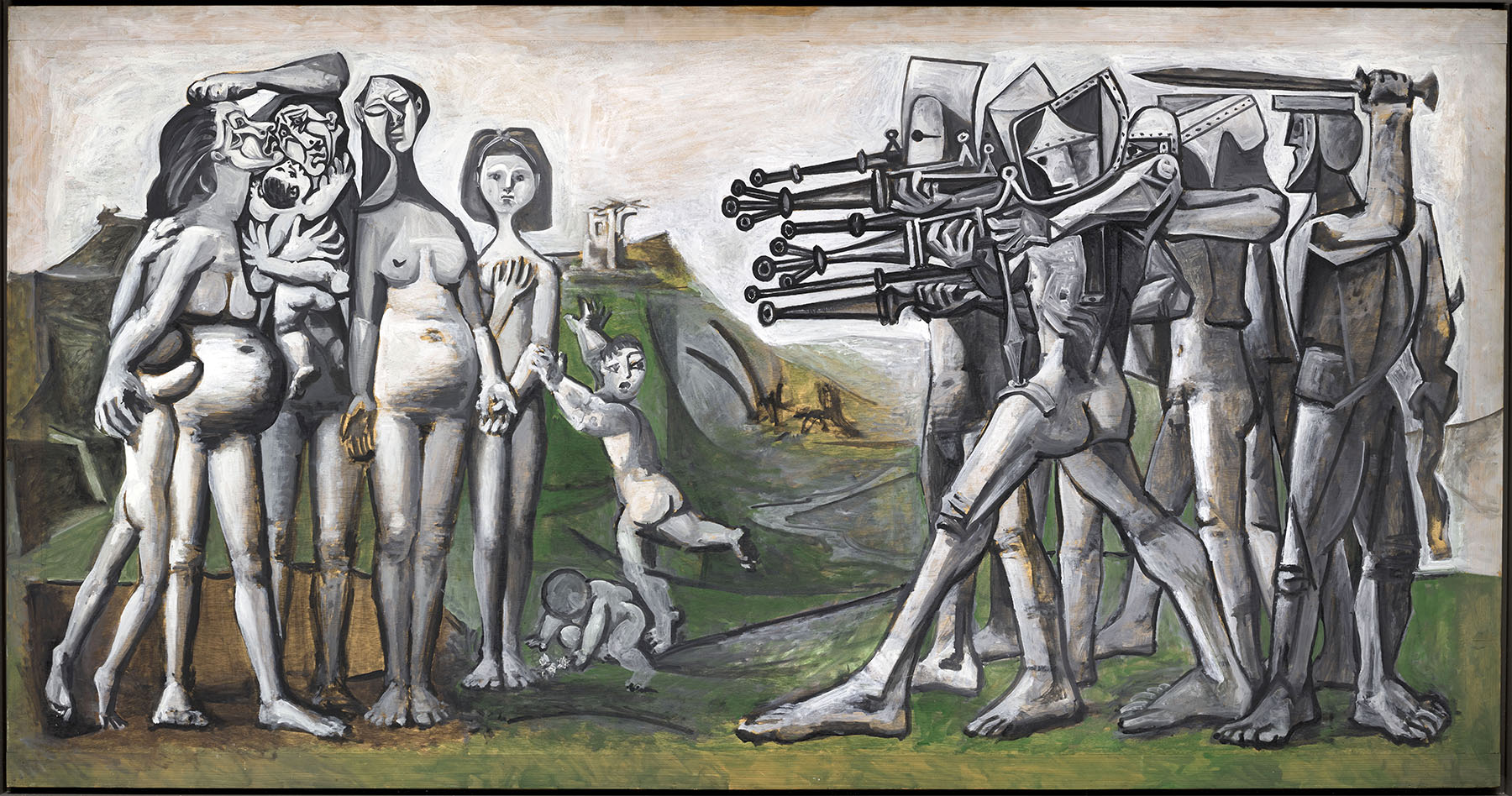

Guernica is quite literally present in a new M+ commission painted by Simon Fujiwara. Called Who vs Who vs Who? A Picture of a Massacre (2024), the large-scale piece with a panoramic sweep is Fujiwara’s response to Picasso’s Massacre in Korea (1951) — believed to be a critique of the American intervention in the Korean War in th 1950s. In Fujiwara’s painting, the women facing the firing squad hold up and point to an image of Guernica, as if trying to reason with the bayonet-carrying soldiers who, as the artist points out, are shown to be “turning into characters from the Guernica painting” from the effect.

Fujiwara’s chosen form is cartoon, which explains why he was drawn to Picasso’s 1912-15 cardboard sculptures of guitars cobbled together from discarded packaging material. They seem to cheekily undermine the sanctity associated with a classical music instrument. On view at the M+ exhibition, Fujiwara’s 2024 pastiche of Picasso’s cardboard guitars has a lolling tongue sticking out of the guitar orifice.

“There is hope and futility in Who vs Who vs Who? in a very obvious way but then everything about a cartoon should be obvious,” says Fujiwara who references the lightbulb that serves as a focal point in Guernica by replacing it with a drone in Who vs Who vs Who?. The silently suffering women in Massacre in Korea are given greater agency in Fujiwara’s reinterpretation. They brandish smartphones and roses at the soldiers as they raise their voices in protest.

The light touch

Though they may not be satirists on the same lines as Fujiwara, quite a few artists featured in Picasso for Asia seem to resonate with Picasso’s humor and playfulness. For instance, Picasso’s Large Still Life with Pedestal Table (1931) is flanked by Feng Guodong’s Body (1978), in which dark paint hangs like treacle from a clothesline, taking on the shape of a human profile with a somewhat sinister smile. Gu Dexin’s part-human, part-bird-or-beast couples with shared torsos in B24 (1983) bring to mind Picasso’s fascination with the figure of the Minotaur from Greek mythology. Both Feng and Gu hark back to Picasso’s depiction of an infinitely mutating world where old, familiar figures morph into bizarre, unknowable creatures.

Isamu Noguchi’s brushed bronze minimalistic sculpture of mating birds is placed in close proximity to Picasso’s Nude Woman in a Red Armchair (1932) and Figures by the Sea (1931) — both erotically charged, outlandish representations of Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s much-younger lover at the time. The paring down of the distinctive features of human figures and faces into simplified forms, comprising lines and circles, is common to all three pieces, almost as if to suggest that from a neutral perspective, passionate love between two people can come across as absurd, if not altogether ludicrous.

“In this exhibition we wanted to bring out some light-hearted and irreverent aspects of Picasso’s work, by juxtaposing them with works by Asian artists who may have that kind of quality,” says Doryun Chong, the artistic director of M+ and also the co-curator of the exhibition with François Dareau, research fellow at the Musée national Picasso-Paris, from where the Picasso originals are on loan for the exhibition.

Picasso’s penchant for humor and satire was certainly not lost on the Japanese designer Tanaami Keiichi. The exhibition includes a selection from the hundreds of paintings based on Picasso’s works that Keiichi made from 2020 to 2024, the year he died.

“He started doing that because he, as an old, frail person, had to isolate himself during the outbreak of COVID-19, which made him feel alienated, lonely and depressed. And the way that he could find some solace, comfort and reassurance was to turn to painting. He was never a painter, but became one and what he painted was Picasso,” Chong says.

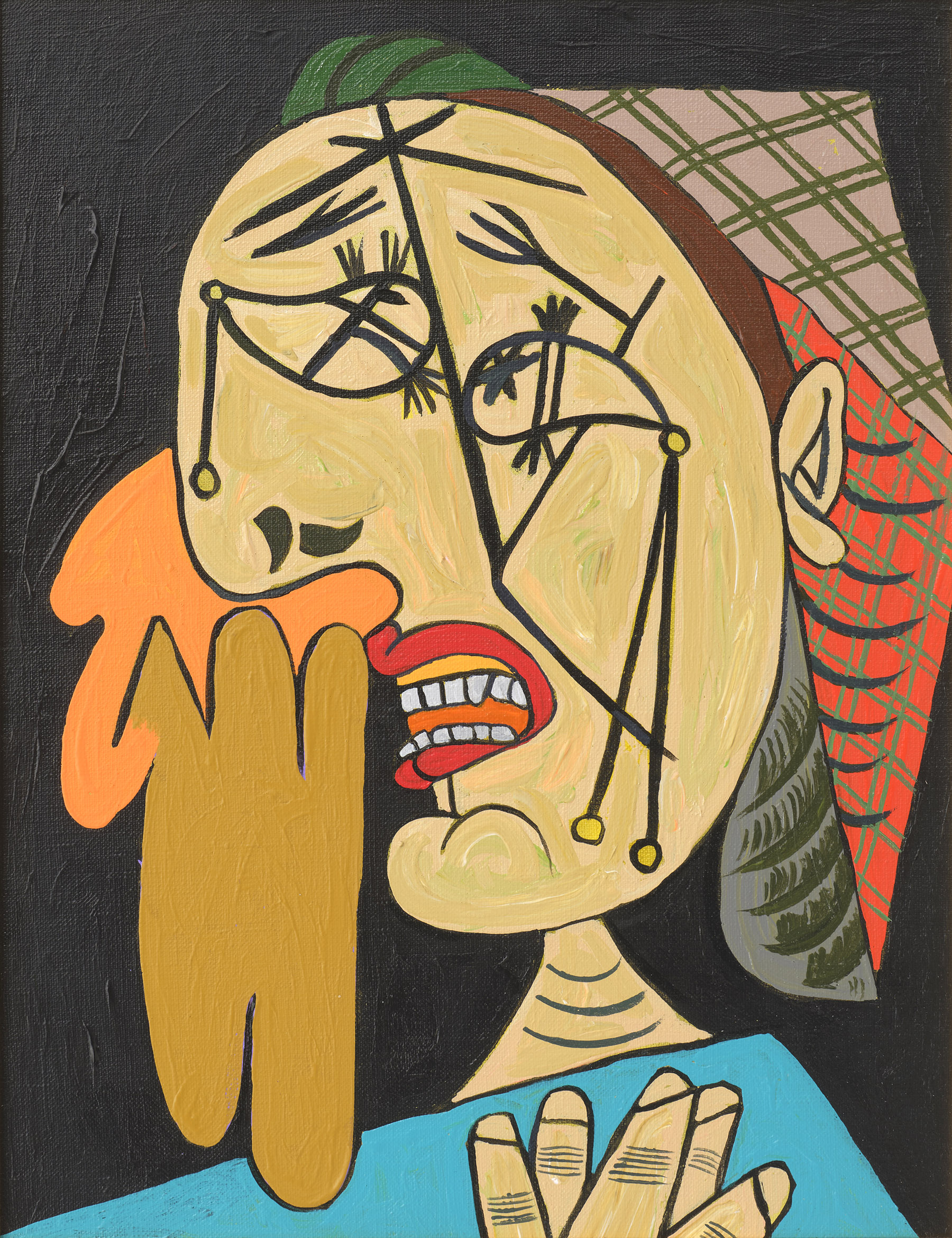

In Keichii’s hands, Picasso’s portraits of intimate mother-child bonding become a caricaturized version of the relationship. Extending a nod to Picasso’s portraits of weeping women with grief-distorted faces, in Pleasure of Picasso — Mother and Child No 118, Keichii paints the mother’s face in profile but showing both eyes, shedding tears that hang like pendulums.

Chong admits that though Keiichi was demonstrably a Picasso fan, not all of his reinterpretations of the master’s works are necessarily adulatory. “I want to emphasize that there are other modes of speaking to Picasso, some of which could be critical. And it’s important that conversations can happen without even intending to.”

Fractured females

Picasso’s portrayals of women can seem to be at odds with present-day sensibilities. More often than not, the women in his works come across as over-simplified, sexualized figures, with exaggerated and distorted features. To make matters worse for the artist, he was by all accounts a narcissist. Many of the female figures reduced to a mass of jagged lines, cones and spheres by him were based on women of exceptional beauty, and, as in the cases of Françoise Gilot and Dora Maar, artistic talent. Almost all of them had been at the receiving end of the artist’s unsavory behavior.

“Picasso famously twisted, fractured, fragmented and molded human bodies, mostly women’s, again and again, like they were made of clay. You can think of that as just a pure endless formal artistic experimentation,” Chong says. On the other hand, “You can also think of his paintings of women as expressions of very complex emotions, including love, lust, anger, melancholy and depression — emotions that Picasso had felt. All those emotions are there for him to distort and redefine and reconfigure in his depiction of female bodies. I think it’s important to see the complexities in how these women were represented.”

Among the Picasso-inspired depictions of women at the M+ exhibition is a piece by the Cuban Chinese artist Wifredo Lam (1902-82), who was friends with Picasso. In Lam’s Woman with a Bird (1949), it is possible to see elements of Picasso’s cubist phase — similar use of near-neutral colors and geometric shapes; his Minotaur phase — the figure is part-human, part-beast; and even the famous Weeping Woman (1937) version of Picasso’s portrait of Dora Maar in the use of sharp, acute angles to suggest a female figure.

To Lam’s son Stephane, the piece demonstrates “Spanish classicism and a syncretism of Afro-Cuban rites, as expressed in the artist’s horse-women series”.

“My father came to Europe in search of freedom of expression that Picasso catalysed by revealing his African side. From there he developed his own artistic grammar,” Stephane Lam says.

In Woman with a Bird, Lam seems to be referring to a classic trope — of paintings showing women caressing pet birds, in which both domesticated women and birds are objectified in a way that might be mutually transferrable. The bird in the woman’s hand is in fact her replica in miniature.

Peace ambassador

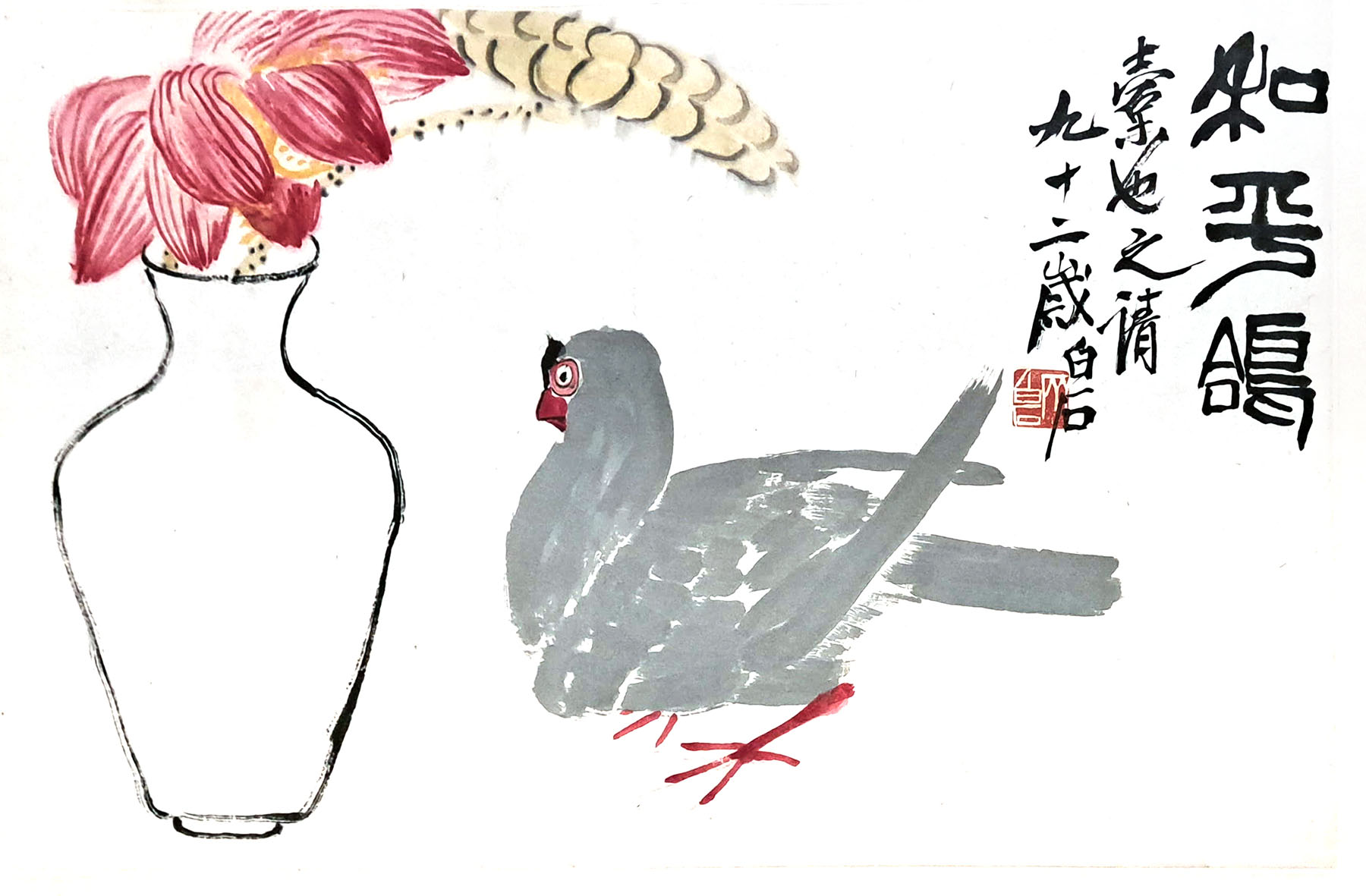

A lithograph showing a white dove against a dark background created by Picasso in 1949 would eventually come to be universally recognized as a mascot of peace. It had a profound impact on Chinese print culture, appearing on posters and magazine covers, a selection of which are on show at the M+ exhibition. Also on display are two adaptations of Picasso’s peace dove by the Chinese master of ink and watercolor, Qi Baishi (1864-1957). Qi includes apples, a vase and lotus flower blossoms in his dove paintings. The additional objects are meant to be picture clues, as the Chinese words for lotus (he) and vase (ping) add up to make heping — the Chinese word for “peace”.

ALSO READ: Golden girl of haute couture blazes a trail

Chong recalls how while conducting research for the M+ show, the curators stumbled on the fact that “Picasso was widely known in China in the ’50s because he was associated with the image of the dove as a symbol of peace.”

He adds that though for most of his life, Picasso steered clear of politics. Once the war in Korea broke out, “he felt that it was imperative to lend his voice and his fame and celebrity to the cause of world peace. And that’s how he started populating his canvases with images of the dove, the symbol of peace”.

“I think Picasso believed that art can transcend the fault lines across a fractured world — that art can give us hope.”

If you go

Picasso for Asia—A Conversation

Dates: Through July 13

Venue: M+, West Kowloon Cultural District, 38 Museum Drive, Kowloon

www.mplus.org.hk/en/exhibitions/picasso-for-asia

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com