A firefighter takes position as smoke rises from a forest fire near Louchats, some 35kms from Landiras in Gironde, southwestern France on July 18, 2022. (PHILIPPE LOPEZ / POOL / AFP)

A firefighter takes position as smoke rises from a forest fire near Louchats, some 35kms from Landiras in Gironde, southwestern France on July 18, 2022. (PHILIPPE LOPEZ / POOL / AFP)

Brutal heatwaves are gripping both Europe and the United States this week and are forecast to dump searing heat on much of China into late August.

In addition to temperatures spiking above 40 C, wildfires are raging across southern Europe with evacuations in towns in Italy and Greece.

The searing heat is part of a global pattern of rising temperatures, attributed by scientists to human activity.

Hotter, more frequent heatwaves

Climate change makes heatwaves hotter and more frequent. This is the case for most land regions, and has been confirmed by the UN's global panel of climate scientists.

Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities have heated the planet by about 1.2 C since pre-industrial times. That warmer baseline means higher temperatures can be reached during extreme heat events.

ALSO READ: Wildfire rages near Athens; homes damaged, hospital evacuated

"Every heatwave that what we are experiencing today has been made hotter and more frequent because of climate change," said Friederike Otto, a climate scientist at Imperial College London who also co-leads the World Weather Attribution research collaboration.

A man puts his bottle in the water of a fountain to cool it down during a heatwave, in Bordeaux on July 18, 2022. (ROMAIN PERROCHEAU / AFP)

A man puts his bottle in the water of a fountain to cool it down during a heatwave, in Bordeaux on July 18, 2022. (ROMAIN PERROCHEAU / AFP)

But other conditions affect heatwaves too. In Europe, atmospheric circulation is an important factor.

A study in the journal Nature this month found that heatwaves in Europe have increased three-to-four times faster than in other northern mid-latitudes such as the United States. The authors linked this to changes in the jet stream - a fast west-to-east air current in the northern hemisphere.

Fingerprints of climate change

To find out exactly how much climate change affected a specific heatwave, scientists conduct "attribution studies". Since 2004, more than 400 such studies have been done for extreme weather events, including heat, floods and drought - calculating how much of a role climate change played in each.

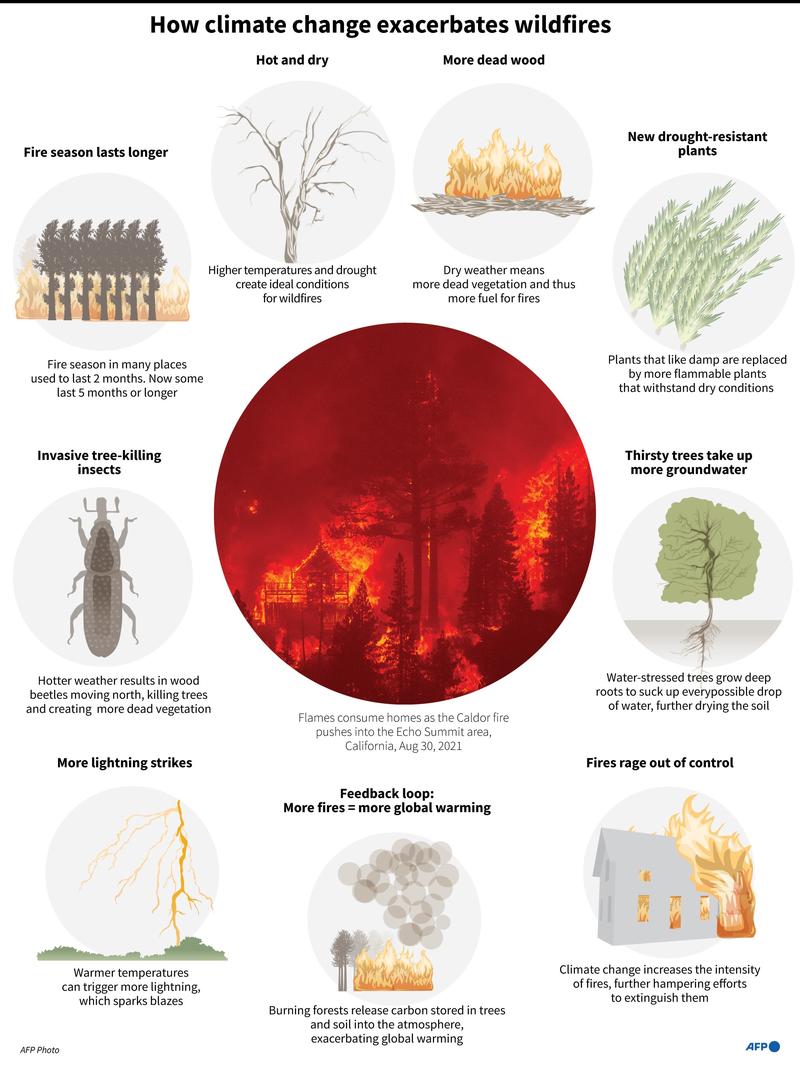

Graphic explaining how climate change can make wildfires worse.(GRAPHIC/AFP)

Graphic explaining how climate change can make wildfires worse.(GRAPHIC/AFP)

This involves simulating the modern climate hundreds of times and comparing it to simulations of a climate without human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

For example, scientists with World Weather Attribution determined that a record-breaking heatwave in western Europe in June 2019 was 100 times more likely to occur now in France and the Netherlands than if humans had not changed the climate.

Heatwaves will still get worse

The global average temperature is around 1.2 C warmer than in pre-industrial times. That is already driving extreme heat events.

"On average on land, heat extremes that would have happened once every 10 years without human influence on the climate are now three times more frequent," said ETH Zurich climate scientist Sonia Seneviratne.

A firefighter stands on a road as heavy smoke is seen in the background during forest fires near the city of Origne, south-western France on July 17, 2022. (PHILIPPE LOPEZ / AFP)

A firefighter stands on a road as heavy smoke is seen in the background during forest fires near the city of Origne, south-western France on July 17, 2022. (PHILIPPE LOPEZ / AFP)

Temperatures will only cease rising if humans stop adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Until then, heatwaves are set to worsen. A failure to tackle climate change would see heat extremes escalate even more dangerously.

Countries agreed under the global 2015 Paris Agreement to cut emissions fast enough to limit global warming to 2 C and aim for 1.5 C, to avoid its most dangerous impacts. Current policies would not cut emissions fast enough to meet either goal.

ALSO READ: Out-of-control wildfire burns 19,000 hectares in Spain

A heatwave that occurred once per decade in the pre-industrial era would happen 4.1 times a decade at 1.5 C of warming, and 5.6 times at 2 C, the IPCC says.

Letting warming pass 1.5 C means that most years "will be affected by hot extremes in the future," Seneviratne said.

Climate change drives wildfires

Climate change increases hot and dry conditions that help fires spread faster, burn longer and rage more intensely.

In the Mediterranean, that has contributed to the fire season starting earlier and burning more land. Last year more than half a million hectares burned in the European Union, making it the bloc’s second-worst forest fire season on record after 2017.

Hotter weather also saps moisture from vegetation, turning it into dry fuel that helps fires to spread.

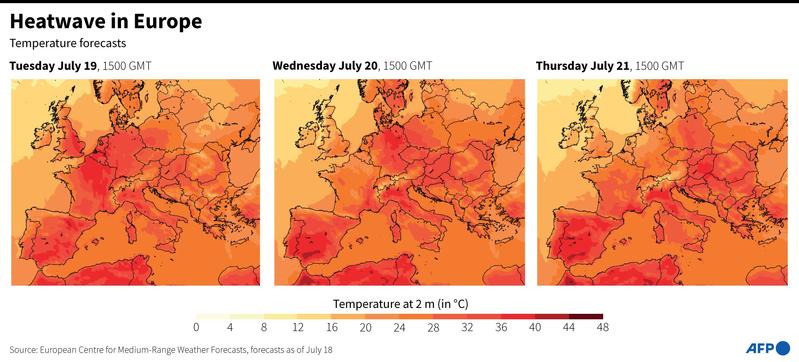

Temperature forecasts for Europe in the coming days, according to the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. (GRAPHIC/AFP)

Temperature forecasts for Europe in the coming days, according to the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts. (GRAPHIC/AFP)

"The hotter, drier conditions right now, it just makes (fires) far more dangerous," Copernicus senior scientist Mark Parrington said.

Countries such as Portugal and Greece experience fires most summers, and have infrastructure to try to manage them - though both have received emergency EU help this summer. But hotter temperatures are also pushing wildfires into regions not used to them, and thus less prepared to cope.

Climate change isn't the only factor in fires

Forest management and ignition sources are also important factors. In Europe, more than nine out of 10 fires are ignited by human activities, like arson, disposable barbeques, electricity lines, or littered glass, according to EU data.

Slovenia's Army helicopters help to extinguish wildfires close to the village of Kostanjevica na Krasu on July 20, 2022. (JURE MAKOVEC / AFP)

Slovenia's Army helicopters help to extinguish wildfires close to the village of Kostanjevica na Krasu on July 20, 2022. (JURE MAKOVEC / AFP)

Countries, including Spain, face the challenge of shrinking populations in rural areas, as people move to cities, leaving smaller workforces to clear vegetation and avoid "fuel" for forest fires building up.

ALSO READ: Southern Europe battles wildfires as heatwave spreads north

Some actions can help to limit severe blazes, such as setting controlled fires that mimic the low-intensity fires in natural ecosystem cycles, or introducing gaps within forests to stop blazes rapidly spreading over large areas.

But scientists concur that without steep cuts to the greenhouse gases causing climate change, heatwaves, wildfires, flooding and drought will significantly worsen.

"When we look back on the current fire season in one or two decades' time, it will probably seem mild by comparison," said Victor Resco de Dios, professor of forest engineering at Spain's Lleida University.