The fan and pair of shoes belong to Kathy Hall, a London-based practitioner of traditional Chinese opera. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The fan and pair of shoes belong to Kathy Hall, a London-based practitioner of traditional Chinese opera. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Exhibition sheds light on Chinese contribution to British life, Xing Yi reports in London.

Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) opened four Chinese ports to foreign trade a mere four years before Shen Fuzong first arrived in what is now the United Kingdom.

It was in 1683, and English people were getting to know more about China through exchanges, with individuals on sailing ships starting to travel more frequently between the two destinations. The Act of Union (1707) put in place the union of England and Scotland under the name of Great Britain.

While Shen, a native of Nanjing, in today's Jiangsu province, was not the first Chinese person to visit England, he was the most recorded visitor of his time, and arguably the most well-known among the early arrivals.

Visitors look at exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Visitors look at exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

During his stay in England, Shen met King James II in 1687, just a year before he was deposed in the "glorious revolution". The king was so impressed that he commissioned a portrait of his guest.

Shen was also hosted by Oxford University, where he collaborated with scholars studying China, and where he helped translate Chinese books in the library and contributed to the creation of a Chinese catalog.

READ MORE: A timeless journey through capital's heart

Shen died from a fever on board the ship while returning home in 1691.

His unique role in history is among stories being shared at an exhibition, titled Chinese and British, that runs until Sunday at the British Library in London.

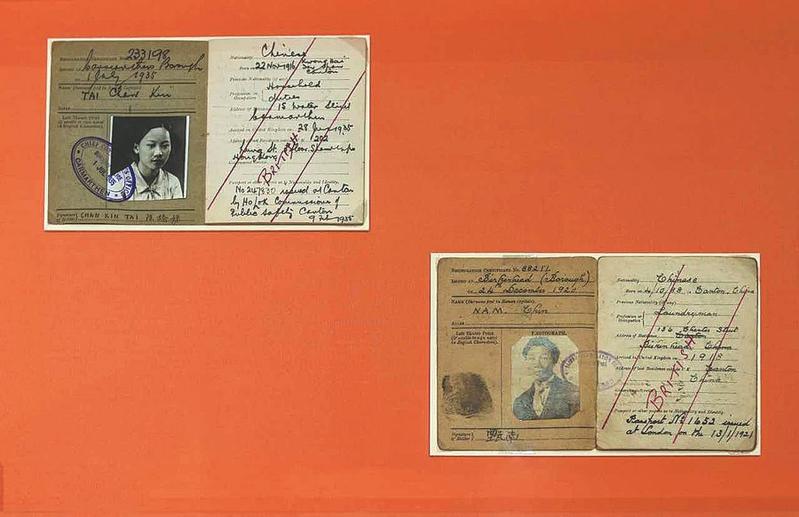

Two identification documents of Chinese immigrants to the UK from the 1920s and '30s. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Two identification documents of Chinese immigrants to the UK from the 1920s and '30s. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The exhibition looks back at the history of the Chinese community in the UK and features a range of stories, with mariners, businesspeople from Chinatown, and wartime workers among those featured alongside Shen.

It is an exhibition that invites visitors to reflect on what it means to be Chinese and British.

Despite there being more than 400,000 people in the UK of Chinese heritage, Lucienne Loh, curator of the exhibition, says the historical presence of the Chinese in Britain is a lesser-known story.

READ MORE: The virtual splendor of Versailles

"I really wanted to expose that kind of history, and to demystify this idea of the Chinese always being part of the catering trade," says Loh, a scholar at the University of Liverpool who has been tracing the historical narratives of the British Chinese community for the past six years.

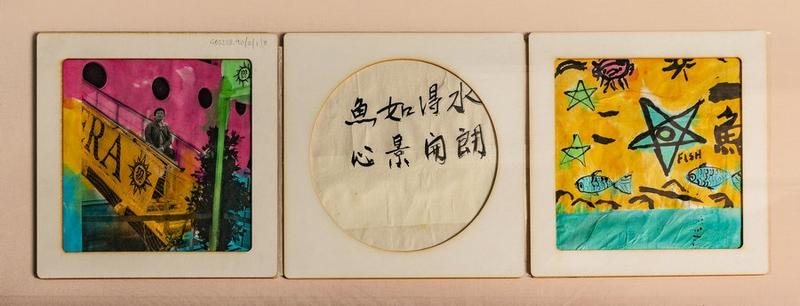

The panels of a folding book created by Chen Mei Li and Robert Liu to depict their stories of migration and express feelings of hope, loss and joy. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The panels of a folding book created by Chen Mei Li and Robert Liu to depict their stories of migration and express feelings of hope, loss and joy. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

"They have a very long-standing contribution to British society, over 300 years, in all different sectors, in every aspect you can imagine," she says of the exhibition she created alongside Alex Tickell, a scholar at the Open University.

"The British Library, being the national library of the country, is a really good platform to showcase this very long history," Loh adds.

Jamie Andrews, head of culture and learning at the British Library, said in an earlier interview that parallel exhibitions with the same theme and adaptations of local history have been held in more than 30 UK public libraries through the British Library's Living Knowledge Network.

A children's jacket holds personal memories and a story of Julia Shang's family, which emigrated from Beijing to the UK in 2013. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A children's jacket holds personal memories and a story of Julia Shang's family, which emigrated from Beijing to the UK in 2013. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

People and places

Divided into three chapters — "people and places", "work" and "culture" — the exhibition displays around 50 items that highlight various aspects of the Chinese community in Britain, with each one carefully chosen and curated.

In a photo of a painting from the 1770s, Chinese sculptor Tan Che Qua is featured by an artist from the Royal Academy, showing his standing in London's creative elite at the time after he set up a business producing highly accurate clay portraits on commission, which resulted in him meeting King George III.

READ MORE: Landscape of the imagination

A bracelet, bearing the contract number and departure port of Tsingtao (now Qingdao, Shandong province) for a worker who was part of the Chinese Labour Corps that toiled during World War I, offers an insight into the largely forgotten story of the 140,000 Chinese workers who served the allies near the front lines, performing noncombat yet important tasks, including trench digging and road repairs. The corps and its contribution were not commemorated for decades following the allies' victory.

Visitors look at exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Visitors look at exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In addition to archives from the British Library, some exhibits are on loan from grassroots Chinese communities, Loh says.

"Those stories are really amazing," she says. "They tell of longing, sorrow, and sacrifice that families and individuals make when they leave their home countries to come here to create a better life for themselves and their children … It's important for us to have community voices."

The description of a rugged duffel bag belonging to Wong Koh Chou, who worked for the UK shipping company Blue Funnel Line, carries a note written by his son that says: "The duffel bag belonged to my dad. It was always in our house in my growing-up days and was put to good use for dirty laundry and when the Rocky films came out, as a punch bag."

And there are audio clips as well that bring visitors closer to individuals and the community as a whole.

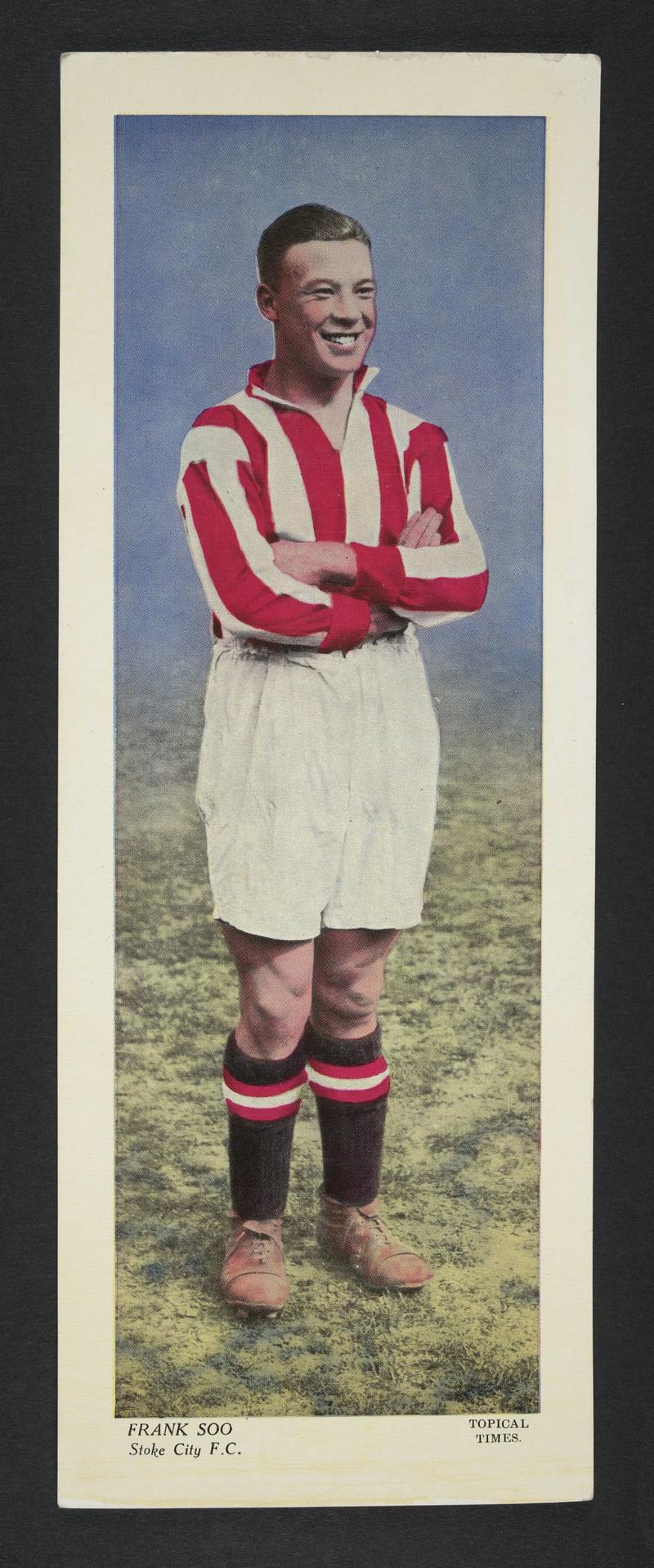

Frank Soo, a Chinese-born soccer player in the United Kingdom in the 1940s, featured on a collectable cigarette card. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Frank Soo, a Chinese-born soccer player in the United Kingdom in the 1940s, featured on a collectable cigarette card. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In an oral history, Vanessa Truong, a Vietnamese Chinese woman, recalls how she worked from a young age in takeaway restaurants and eventually started her own business, in which she introduced more vegetarian food, which matched her passion for healthy eating.

"Those kinds of stories are just really powerful because they're not just personal stories. They are stories about other people's journeys," says Loh. "They are collective stories."

READ MORE: Celebrating the Gandhara art

There is also a patent from Charles Kuen Kao, who was born in Shanghai and came to the UK as a student in 1953. He was awarded as joint Nobel Prize winner in physics for his work on fiber optics and digital communication.

From the field of sports, there are photos of Frank Soo, who, in the 1940s, became the first Chinese-born athlete to play professionally in an English soccer team. And there is Emma Raducanu, the current professional tennis player who is ranked No 1 in the UK and who has a Chinese mother.

Exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Cultural impact

The last section of the exhibition looks at some of the many Chinese people who have been influenced by British culture and who, by incorporating both Chinese and British elements into their style, have made a lasting impact on Britain's cultural landscape in literature, fashion, music and film.

Among them is Chiang Yee, one of the first Chinese people to write books in the English language. Chiang came to Britain in 1933 and wrote a series of successful travelogues under the pen name Silent Traveler.

His books, written from an outsider's perspective, provide a fresh angle on the culture, and are still reprinted and sold today.

As a painter and poet, Chiang illustrated his books with his own landscape paintings that capture his view of the scenery of England, Scotland and Ireland. He also translated his poems into English.

Visitors look at exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Visitors look at exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The exhibition also shows a transnational literary friendship between Ling Shuhua, a modernist Chinese female writer, and Virginia Woolf.

In a letter written in 1938 that is displayed at the exhibition, Woolf encourages Ling's writing, and says: "At last I have read the chapter you sent me … Now I write to say that I like it very much. I think it has a great charm … I feel a charm in the very unlikeness."

ALSO READ: Exhibition frames era rich in culture and art

And Woolf also gives her advice: "Please go on; write freely; do not mind how directly you translate Chinese into English. In fact, I would advise you to come as close to the Chinese (language) both in style and in meaning as you can."

In 1953, Ling published her autobiography, Ancient Melodies, which reflects her feminist outlook and is dedicated to Woolf.

Once limited to elite literary circles, since the 1930s, the creative output of Chinese writers and artists has grown in popularity and seen mainstream success.

Exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Exhibits at the British Library in London. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Toward the end of the exhibition, a table of books showcases the poetry and prose of UK-based writers of Chinese descent, which explore themes including hybrid identity, migrant journeys, and ancestral memories.

Loh says: "One of the most important things for visitors to learn from the exhibition is that there is China, the country which is in the news a lot, and then there's also the Chinese community (members) in Britain who are as British as the next person you know.

"The Chinese community in Britain is very well-established and long-standing … and there is an ever-increasing contribution by the Chinese to British society."

Contact the writer at xingyi@chinadaily.com.cn