In the second installment of her series on Greater Bay Area museums reinterpreting the history of the Silk Road for a new audience, Chitralekha Basu finds out how Guangzhou, Macao and Hong Kong were key ports on the ancient Maritime Silk Road, resulting in a shared ethos that continues to this day.

Amid the bustle and din of Tsim Sha Tsui, in a leafy oasis of repose called Kowloon Park, the Hong Kong Heritage Discovery Centre is hosting without much fanfare an important exhibition on the origins of maritime trade in what is today’s Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Nanhai I Shipwreck and the Maritime Silk Road is built primarily around the archaeological relics excavated from a merchant ship that by all indications had set sail from Guangzhou but sank 19 kilometers southwest of Xiachuan Island, off the coast of Guangdong province, in 1183, or shortly afterward. Packed to capacity with export goods, the vessel was likely heading toward the Middle East, as the Islamic pear-shaped ewers with narrow curved spouts and jewelry with pomegranate motifs recovered from it seem to suggest. Remarkably intact even after a millennium under water, the ship was dredged up in 2007, christened Nanhai I, and installed in the Maritime Silk Road Museum of Guangdong in Yangjiang. An astounding 180,000 sets of artifacts, including 160,000 pieces of high-quality ceramic, have been retrieved from its cavernous cargo holds.

READ MORE: Tapestry of cultural connections

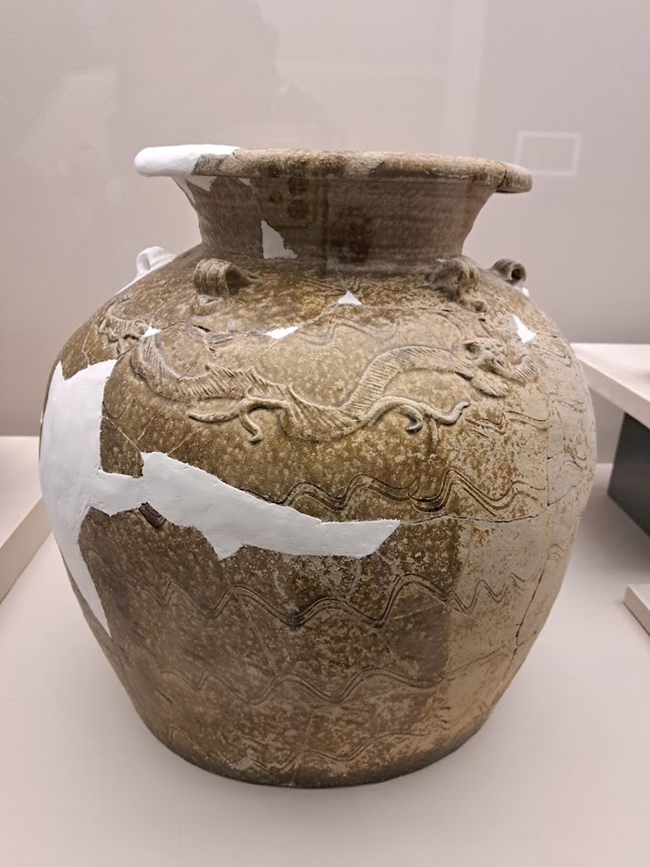

Lee Hiu-wai, assistant curator (archaeological preservation) of the Antiquities and Monuments Office, explains that the exhibition is the result of “a treasure hunt”. Taking the massive assortment of Kwangtung jars — traditional ceramic storage vessels, typically with two or more lugs around the neck — found in Nanhai I’s cargo holds, numbered 9 and 10, as the starting point, a team of researchers and archaeologists tried backtracking their way to the source. “A lot of similar jar fragments have been recovered from an erstwhile winery discovered around the back of the palace courtyard of the Nanyue Kingdom in Guangzhou. Those jars and the wine residue found inside them match the ones found in Nanhai I,” Lee says.

“The Kwangtung jars located in Nanhai I look very likely sourced from Guangzhou kilns,” she continues. “After they had dated their finds and conducted material analyses, the team zeroed in on three locations.” These were the Qishi and Wentouling kilns in Nanhai (district in Foshan), where the jars were made, the site of the palace of the Nanyue Kingdom, where the jars were stacked together for shipment, and Nanhai I itself. “And it is these Kwangtung jars that link them up.”

In the same spirit

While Nanhai I serves as the show’s epicenter, the archaeological treasures salvaged from it are shown to resemble, or resonate with, relics found in different locations across the Pearl River Delta — from Sai Kung and Lantau Island among several others in Hong Kong to the St. Paul’s College site in Macao. The exhibition connects the three cities of Hong Kong, Macao and Guangzhou, not only in terms of shared maritime routes, and the flow of objects between them, but also in terms of a shared ethos.

For instance, samples of Kwangtung jars recovered from Nanhai I and the Sacred Hill site in Hong Kong’s Kowloon City are shown to bear stamps of the same brewer. During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the making and consumption of wine was a significant part of the social lives of maritime traders running their business from Guangzhou port. The local government had a monopoly on brewing wine, as the discovery of the site of the official wine storehouse in 2019 — literally in the backyard of the palace of the Nanyue Kingdom — helps establish. However, a wall text from the exhibition reveals that to keep up with the growing demand, especially from the non-Han consumers residing “at the border”, the restriction on private wine-making enterprise was eventually lifted.

The policy shift would help archaeologists many years later, for private brewers often stamped and dated their products. Two objects in the exhibition — a luminous Qingbai glazed white porcelain jar and a brown wine jar with lugs — display the same year of production, marked in ink. Lee says that the double proof adds weight to archaeologists’ deduction that Nanhai I did indeed sail, and sink, in 1183 or shortly afterward.

During the Song and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties, Guangzhou and Hong Kong seemed to share a tea culture as well. To illustrate their shared cultural quirks, a black-glazed tea drinking bowl (960-1368) from the Yulinting Kiln, Fujian province, unearthed in 1998 at Ho Chung in Hong Kong’s Sai Kung and another one recovered from Nanhai I appear side by side at the exhibition. The Chinese characters shou shan fu hai (mountain of longevity and sea of happiness), inscribed on the inner surface of the first, have since been partially lost to decay. “The glaze in the Nanhai I bowl is better preserved. You can almost see your reflection on it,” Lee says. “But both pieces belong in the same family, and were made in the same area.”

Hong Kong heritage

The exhibition highlights Hong Kong’s role as a key player on the ancient Maritime Silk Road — alongside the more obvious port cities Guangzhou and Macao, both of which served as major ports of entry for merchant vessels heading to the Chinese mainland via a river network. The show confirms that Hong Kong has always played its part in maritime trade, both as a port of transit as well as a ceramic manufacturing hub. From Penny’s Bay to Lamma Island, the soil of Hong Kong seems to be a never-ending subterranean reserve of ancient ceramic.

The Sacred Hill site in Kowloon City has yielded the largest haul of archeological relics, mostly by-products of the ongoing Kai Tak Development program. “In recent years, we have discovered 900,000 pieces of ceramics, as well as remnants of houses from which we get an idea of people’s livelihoods,” Lee says. “Ceramic manufacturing has always been part of the city’s culture,” she continues. “For example, a lot of ceramic products were made, mainly for export, at the Wun Yiu Kiln Site in Tai Po in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties,” She adds that in fact Hong Kong’s ceramics-making history goes much further back, well into the Tang (618-907) and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907-960) periods.

Ceramic is the preferred medium of a number of contemporary Hong Kong artists, including internationally recognized stalwarts such as Rosanna Li and Fiona Wong. Their choice of medium is perhaps owed to centuries of collective memory. For her reimagined ceramic versions of ceremonial clothes worn by Chinese officials in the Han dynasties (206 BC-AD 24, 25-220) and Song Dynasty, Wong manipulates glazed porcelain as if it were putty in her hands and with a robust confidence that might have something to do with her Hong Kong heritage.

Guangzhou, the pottery hub

Both Lee and Wang Siyu — a curator at the Museum of Two Mausoleums of Southern Han State in Guangzhou — contend that when it comes to the Maritime Silk Road, Guangzhou has traditionally served as China’s main gateway to the rest of the world. Wang, who co-curated the From Central China to the Sea: Gongyi Kiln and the Maritime Silk Road exhibition, says, “Guangzhou is the eastern terminus of the Maritime Silk Route. It has prospered for over 2,000 years as a vital port and commercial hub.”

Putting on a show that tells the story of how Guangzhou “emerged as a crucial distribution center for the prized ceramic ware from the Gongyi kilns in Henan province during the Tang Dynasty”, at a historic site — itself a treasure chest of archaeological discoveries from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms — adds an extra layer of meaning to the project.

The Guangzhou port played a role in raising the stocks of Gongyi’s generic white-yellow-green glaze tricolor pottery, internationally, during the Tang period. Some of the tricolor objects displayed at the exhibition were likely targeted at the export market. For instance, a tricolor phoenix ewer looks like a copy of similar Persian gold and silver utensils, realized in ceramic. Wang points out that the technique used to emboss the motifs of phoenixes and hunting figures on the ewer’s surface mimics that of applying relief decoration on precious metal. “Here the artisan has cleverly combined elements borrowed from an alien culture with a local ceramic crafting technique, to make an object of everyday use with a high aesthetic value,” says the curator.

“The exhibition highlights Guangzhou’s role as a commodity distribution hub on the Maritime Silk Road. It also demonstrates East-West trade relations and cultural exchanges, reflecting the diversity, openness and inclusivity characterizing the Chinese civilization.”

Macao mosaics

Some of the architecture and design elements of the new Poly MGM Museum in Macao seem to invoke the spirit of the ancient mariners taking a voyage along the Maritime Silk Road — the theme of the museum’s inaugural exhibition. A set of 12 large floor tiles, each with distinct traditional cultural motifs symbolizing a country on the historic Silk Road, are inlaid into the museum’s floor.

Curator Su Dan, who is deputy director of the China National Arts and Crafts Museum and the China Intangible Cultural Heritage Museum, says that “the 12 traditional cultural totem patterns representing countries along the Silk Road have been arranged sequentially from East to West according to their geographical distribution”. Together, they mark “the cultural pathway of the Silk Road on a global map”.

He goes on to explain that the design is a reference to Macao’s “unique port location” on the Maritime Silk Road map and is meant to serve as “an enduring carrier of historical information”. Su adds that “the patterns were crafted using traditional stone mosaic techniques, with materials sourced from various parts of the world, such as Amazon Green Stone, Dragon and Phoenix Dance stones from Brazil, Wood Grain Stone from Canada, and Red Rose Stone from France. The design aims to demonstrate the coexistence and fusion of multiculturalism in Macao, while also positioning the city in the global art coordinate.”

A rather large tapestry from 1620, depicting a scene from the Trojan War, looks down on visitors from a museum wall. Called Aeneas and Anchises, it is one of seven such existing Trojan War-themed works. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has one.

Though it brings Italian maestro Raphael’s (1483-1520) iconic sketch based on the same theme to mind, the tapestry, created by unnamed artisans, could not be more different. Much about the scene, showing a man carrying his elderly father on his back as they try to flee from the scene of the battle, is distinctly Chinese. Su says that the piece was probably completed in Macao, resulting in a number of Chinese elements getting assimilated into a Western-style tapestry.

ALSO READ: The timeless allure of lavish clocks

“For instance, the waves serving as the backdrop and the white clouds in the sky are typical Chinese motifs,” he points out. “Additionally, along the borders of the tapestry, one can spot Chinese phoenixes and floral patterns. Hence, this piece stands as an important testament to the cultural exchanges between China and the West over the centuries.”