A general view of a large Philippine national flag being raised during the Independence Day celebration at the Rizal monument in Manila on June 12, 2019. (TED ALJIBE / AFP)

A general view of a large Philippine national flag being raised during the Independence Day celebration at the Rizal monument in Manila on June 12, 2019. (TED ALJIBE / AFP)

Lops Calzado was three years old when former Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos was ousted after two decades, accused of plundering government coffers and killing thousands under a dictatorship that set the country back years.

Now, she’s being swamped by Facebook and YouTube posts telling her that his rule was a golden era when food was affordable, streets were safer and new highways were built.

The online experience of Calzado, now 38, is emblematic of that of many voters in the Philippines. As the nation of 110 million people gears for elections in May, it has become a textbook case for developing democracies on how social media can turn voters.

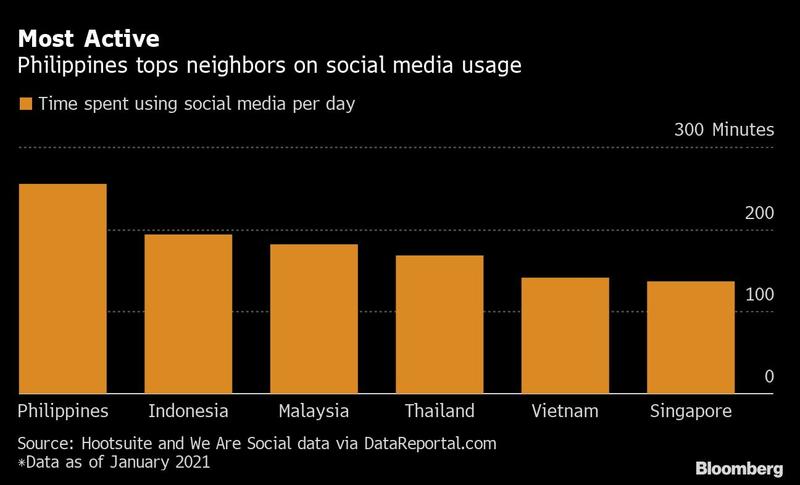

Two-thirds of Filipinos have internet access and they are more active on social media than in other Southeast Asian countries, according to We Are Social and Hootsuite. And the reliance on smartphone-delivered opinion has been supercharged by the pandemic.

Calzado says she spends more than 18 hours online daily as part of her job at a marketing company. After she clicked on a YouTube video of a blogger denying that Marcos was corrupt and violated human rights, she started getting content on Facebook campaigning for his son Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.

“There are so many positive posts about Marcos in social media that I’m seriously considering him,” Calzado said, adding that she still hasn’t made up her mind.

The Nobel Peace Prize awarded this year to journalist Maria Ressa highlighted the problems facing the Philippines. In an October interview, Ressa - who frequently came under attack from Rodrigo Duterte and his government - likened disinformation on social media including Facebook to an “atom bomb” for public discourse and called for more laws to counteract it

Ahead of the May 9 election, Marcos Jr currently holds a commanding lead in both opinion polls and online dominance. His internet presence, particularly on Facebook, is reminiscent of the successful 2016 presidential run by Rodrigo Duterte, who the company at the time called the “undisputed king of Facebook conversations.”

The hashtag bearing Marcos Jr’s name on ByteDance Ltd’s video app TikTok also leads other presidential candidates with 840 million views, including videos calling his father “the best president of the Philippines.”

As one of Asia’s most free-wheeling democracies, the Philippines is particularly vulnerable to the same misinformation campaigns and hate speech that have generated criticism of Facebook in the West.

US whistleblower and former Facebook product manager Frances Haugen has said that the company neglected developing regions that are more at risk of real-world harm from negativity on social media.

‘Atom Bomb’

At the heart of the debate is the question of whether the social media posts are part of an organized, funded campaign by a candidate, or the result of die-hard fans using the internet to voice their views.

The murky online world makes it difficult to tell the difference between content purposely created to deceive voters and campaign spin that is standard in social-media strategies around the globe.

The Nobel Peace Prize awarded this year to journalist Maria Ressa highlighted the problems facing the Philippines. In an October interview, Ressa - who frequently came under attack from Duterte and his government - likened disinformation on social media including Facebook to an “atom bomb” for public discourse and called for more laws to counteract it.

The Philippines has yet to pass a “fake news” law, even as other nations in Southeast Asia have pressed ahead with legislation to deter misinformation.

ALSO READ: Facebook issues correction notice under new S'pore fake news law

Already, we have seen that certain celebrities and social media influencers have shared misleading information about political candidates to millions of their followers ... During this important upcoming vote, disinformation risks directly undermining electoral integrity and voters’ ability to engage in meaningful debate and access reliable information.

Manisha Vepa, research associate at Freedom House, a Washington-based advocacy group

“Already, we have seen that certain celebrities and social media influencers have shared misleading information about political candidates to millions of their followers,” said Manisha Vepa, research associate at Freedom House, a Washington-based advocacy group. “During this important upcoming vote, disinformation risks directly undermining electoral integrity and voters’ ability to engage in meaningful debate and access reliable information.”

In an interview streamed on Facebook in late October, Marcos Jr said online discussions about him and his family are “not scripted” and are part of the “natural reaction of people.” He said his team doesn’t employ online trolls and isn’t boosting his social media pages because “netizens are smart and they would know.”

Bloomberg called, sent mobile phone messages and e-mails to his spokesman and media team. They acknowledged the requests for comment and said an official statement will be issued when available.

In 2016 an army of online personalities helped bolster Duterte’s popularity and attack his enemies, and his control of social media continued throughout his presidency, according to VERA Files, a media organization used by Facebook for fact-checking.

The Marcoses were also among the top beneficiaries of disinformation in recent years, said Celine Isabelle Samson, who heads VERA Files’ online verification team. “We expect election-related disinformation to ramp up online, especially with the mobility restrictions amid the Covid-19 pandemic,” she said.

In this Feb 28, 2021 photo, Rodrigo Duterte, the Philippines' president, addresses officials during a vaccine arrival ceremony at Vilamor Airbase in Pasay City, Manila, the Philippines. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

In this Feb 28, 2021 photo, Rodrigo Duterte, the Philippines' president, addresses officials during a vaccine arrival ceremony at Vilamor Airbase in Pasay City, Manila, the Philippines. (PHOTO / BLOOMBERG)

Some of Duterte’s most ardent online supporters are now helping out Marcos Jr One of them, a 37-year-old call center employee who uses the alias Ace Gatumbato, used 12 Facebook and Twitter accounts to defend Duterte’s administration and attack the opposition, posting to 20 social media groups with as many as 60 members each.

He said he isn’t paid and does it to ensure and “no opposition candidate will be put into national public office.”

Changing History

A 37-year-old call center employee who uses the alias Ace Gatumbato, used 12 Facebook and Twitter accounts to defend Rodrigo Duterte’s administration and attack the opposition, posting to 20 social media groups with as many as 60 members each

Gatumbato, who asked to be identified by his alias on concern about retaliation at work, said he tells readers that only communists were killed under Marcos’s regime and that murdered opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr worked with the then-communist party leader.

“I make them look good,” Gatumbato said of the Marcoses. Revising history, “is basically in people’s minds. Not all things in the history books are true. They are just written by the victors.”

The late Marcos took his family into exile in Hawaii in 1986, amid mass protests fueled by accusations of theft and the murder of Aquino Jr three years earlier. A presidential commission found that the former dictator had stolen as much as $10 billion from state coffers, of which $3.38 billion had been recovered as of end-2015.

ALSO READ: Philippines election drama builds, Duterte move eyed

In the final years of Marcos’s rule, the country suffered its first economic contraction since Bloomberg started tracking the data dating back to 1947. The country’s foreign debt swelled 43 times to $26 billion during his time in office, according to World Bank data.

Marcos Jr returned to the Philippines in 1991 shortly after his father’s death, and ran unsuccessfully for the Senate in 1995. It wasn’t until 2010 that he won a seat in the upper house, and he narrowly lost the vice-president race to opposition leader Leni Robredo in the last election.

In the Philippines, the president and vice-president are elected separately and aren’t necessarily from the same party.

‘Outrageous’

“The Duterte and Marcos machineries are factories of disinformation” that Robredo’s team has been fighting since 2016, said Barry Gutierrez, spokesman for the vice-president, citing online reports accusing her of affairs and speculating about her husband’s death in a 2012 plane crash.

Robredo trails Marcos Jr by nearly 30 percentage points in the presidential race, according to an October Social Weather Stations survey

“Some of the things are so outrageous that we thought nobody would believe them,” Gutierrez said. “But it’s repeated over and over again.”

Robredo’s team has started her own network of social media volunteers that has now grown to more than 50 groups, Gutierrez said, adding that none is paid. Still, he acknowledged that was nothing compared to their political opponents.

This illustration picture taken on May 28, 2020 shows social media applications logos from Linkedin, YouTube, Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter displayed on a smartphone in Arlington, Virginia. (OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP)

This illustration picture taken on May 28, 2020 shows social media applications logos from Linkedin, YouTube, Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter displayed on a smartphone in Arlington, Virginia. (OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP)

For platforms like Facebook and YouTube, which are regularly attacked for allowing fake news, the line between deliberately misinforming the public and running a strong social media campaign is difficult to police

For platforms like Facebook and YouTube, which are regularly attacked for allowing fake news, the line between deliberately misinforming the public and running a strong social media campaign is difficult to police.

Long-Term Challenge

Facebook taps fact-checkers to flag content that misrepresents history, said Alice Budisatrijo, the company’s lead on misinformation policy in Asia-Pacific. The posts come “with a slightly softer label” warning about missing context.

“A lot of times, the content may not be fully false, because there may be some truth in their argument, but they exaggerate something,” she said.

YouTube said it has policies on election misinformation and updated its hate policy in 2019 to “remove content denying well-documented violent events, including certain events that took place during the martial law in the Philippines.”

READ MORE: S'pore tells Facebook to correct user's post under 'fake news' law

It relies on a combination of technology and 20,000 people around the world to enforce its policies. TikTok has yet to respond to Bloomberg’s request for comment.

Collaborative fact-checking can help verify legitimate news and debunk fake content, Vepa at Freedom House said. Still, the problem of disinformation can’t be solved in a few months “with only minor tweaks to existing practices,” she said. “This is a long-term challenge that will need long-term solutions.”