The 5,000-metric-ton scientific research vessel Haiyang Dizhi 6 leaves Dongguan, Guangdong province, for a voyage to the Xisha Islands in the South China Sea. (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

The 5,000-metric-ton scientific research vessel Haiyang Dizhi 6 leaves Dongguan, Guangdong province, for a voyage to the Xisha Islands in the South China Sea. (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

Research vessel gives oceanographers better picture of undersea depths

As Hong Kong marine scientist Ivy Cheng Aifang stared at computer monitors, an operator by her side carefully pushed forward a joystick under Cheng's instructions.

Almost instantaneously, some 1,400 meters beneath the sea surface, a robotic arm quietly advanced, placing deep-sea mussels and sea anemones it gathered in a preservation device.

It was the first time that Cheng had worked with this sophisticated equipment aboard the 5,000-metric-ton scientific research vessel Haiyang Dizhi 6 (Ocean Geology No 6), which was making a voyage to China's Xisha Islands in the South China Sea, about 600 kilometers from Hong Kong.

Cheng, a research assistant professor at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, or HKUST, was one of four Hong Kong scientists on the expedition, which was led by colleagues from the Chinese mainland.

Since Hong Kong's return to the motherland in 1997, the city has accelerated its integration into the nation's overall development, resulting in more cross-border collaboration among the marine science community

As high-definition images were received from a camera attached to a remotely operated underwater vehicle, or ROV, Cheng and the other scientists in the vessel's cramped cabin were excited about the deep-sea samples they were about to receive.

Marine life and microbes that survive in the dark, oxygen-deficient and high-pressure depths of the sea have different characteristics from ordinary creatures, Cheng said.

ALSO READ: Troubled waters

She wants to study the marine life and microbes, and hopes to extract compounds from them that could be used to treat neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's.

Cheng said many deep-sea creatures begin to die, or experience stress when they leave their habitat, and both factors could lead to rapid changes in their bodily functions or protein structures. The preservation device, which acts like a refrigerator, can slow these processes and give scientists time to study such creatures and perform experiments on them in the ship's laboratory, she said.

The shorter the time between sample collection and experimentation, the more time there is for observation and discoveries, Cheng said. This is also why marine scientists need to take part in ocean research expeditions, rather than merely waiting for samples to be sent to onshore laboratories, she added.

During the trip, which lasted nearly one month, Cheng and her colleagues carried out six deep-sea missions to collect creatures by using the ROV, and conducted three experiments in the vessel's laboratory.

However, it was not all plain sailing for Cheng, who joined the voyage during the COVID-19 pandemic.

After leaving Hong Kong, she underwent 14 days' hotel quarantine in late March before entering the mainland. She then spent several days completing a series of checks to see whether she was in good health for the mission. In addition, all members of the expedition underwent several rounds of testing for COVID-19 before departing.

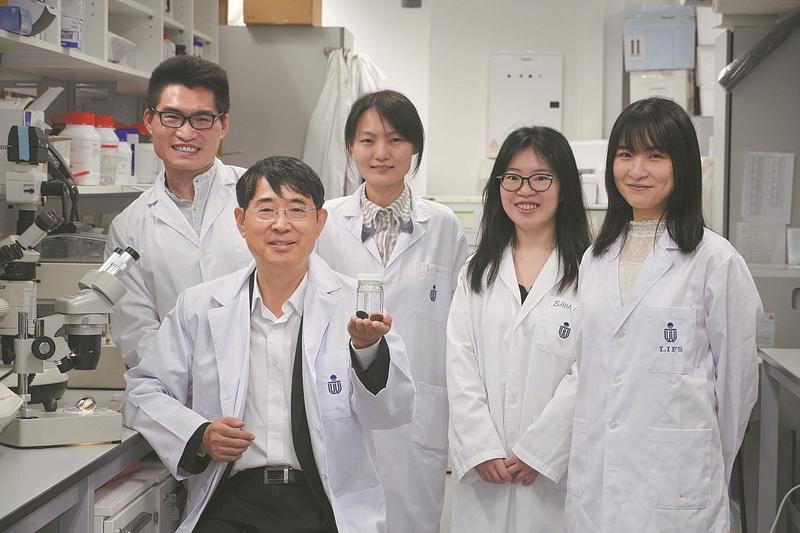

Qian Peiyuan (second left) poses with members of the Hong Kong branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou). (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

Qian Peiyuan (second left) poses with members of the Hong Kong branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou). (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

The departure time and date were also adjusted several times due to outbreaks of the disease in Guangdong province in March and April, but the research ship eventually left Dongguan on May 17.

Dozens of marine scientists were aboard, mostly from the mainland. To make the best use of time, and to allocate the limited amount of equipment such as ROVs, Cheng and other scientists worked in turns for a few hours, or even a whole day.

For example, conducting an underwater operation with an ROV counted as a single turn, which usually took four to eight hours. "The longest turn I worked was just over 24 hours, and I then rested for a day before going for the next turn," Cheng said.

Her work often began after sunset. She said that at night, the temperature on the ship — especially the deck — is lower, which creates a better environment to preserve deep-sea samples.

Seasickness and irregular working hours challenged Cheng mentally and physically, but she persevered with her work.

"Without the nation's support, I would not have been able to join the expedition and carry out oceanographic research, which gives me a better understanding of deep-sea creatures and the ocean environment," Cheng said.

The ocean and organic marine life were not the only things that Cheng got to know better. During the trip, she was impressed after being told of the presence of Chinese naval stations on nearby islands. "That made me feel safe throughout the journey," she said.

Stronger development

Cheng and her marine scientist colleagues in Hong Kong were recommended for the mainland-funded ocean expedition by the institution they work for — the Hong Kong branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou) at HKUST.

The branch, established in 2019, was cofounded by the Innovation Academy for South China Sea Ecology and Environmental Engineering at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Guangzhou Science and Technology Innovation Committee, and HKUST. The branch aims to strengthen marine science development in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and promote cross-border collaboration for Hong Kong oceanographers.

Qian Peiyuan, a veteran marine scientist and director of the branch, said Hong Kong could play a bigger role in the national marine economy blueprint and ocean governance. The city has many world-class research universities and talent, and in recent years it has paid more attention to technology and innovation, he added.

Hong Kong occupies a sea area of 1,641.21 square kilometers. Known for its shortage of land, the city has reclaimed 77.6 sq km from the sea over the past 130 years. It also boasts a world-class container port — the Kwai Tsing Container Terminals — and Victoria Harbour.

However, the city is little-known for its marine science. In the 2022 QS World University Rankings, three universities in Hong Kong ranked among the top 50 in the world — the University of Hong Kong, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and HKUST. However, for Earth and Marine Science, only one of these universities was ranked 50th-100th, while the other two were not in the top 100.

A remotely operated underwater vehicle is raised from the sea near the Xisha Islands. (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

A remotely operated underwater vehicle is raised from the sea near the Xisha Islands. (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

Qian, who has studied oceanography in Hong Kong for nearly 30 years, said that for historical and political reasons, the city's marine science community pays little attention to waters beyond the city's boundary, and mainly focuses on marine biology in local waters, including environmental protection and pollution control.

Although marine conservation and diversity protection is important to Hong Kong, marine science covers a much broader spectrum, involving physics, chemistry, geography, among other topics, Qian said.

Since Hong Kong's return to the motherland in 1997, the city has accelerated its integration into the nation's overall development, resulting in more cross-border collaboration among the marine science community.

Hong Kong's first national-level marine laboratory, the State Key Laboratory of Marine Pollution, was established at City University of Hong Kong in 2010. A branch of the laboratory was also opened at Education University of Hong Kong in 2018.

In 2019, Cheng's institution opened and studied the ecosystem and ecological safety in the South China Sea, including the Greater Bay Area, and new technologies for mining biological and microbiological resources in the region.

Over the past three years, dozens of researchers from HKUST and other local institutions have been recommended by Cheng's institution to take part in four state-funded expeditions in the South China Sea and the Pearl River estuary. Such an opportunity, which occurs once a year on average, allows more Hong Kong researchers, especially the younger generation, to gain first-hand experience and an insight to marine science.

ALSO READ: Shoring up the coastlines

Last summer, Frances Xiao Yao, 26, who is studying marine environmental science at HKUST, boarded a research vessel bound for the South China Sea. Before studying in Hong Kong, Xiao completed her undergraduate education in marine science on the mainland, but had yet to join an ocean expedition. The journey proved to be an eyeopener for the young scientist.

"Through the ROV's cameras, I saw the real deep-sea environment and the way in which samples were collected. The trip gave me a deeper understanding of the complexity of this environment," she said.

Taking part in these programs gives Hong Kong oceanographers a rare opportunity for face-to-face communication with their mainland counterparts, as most cross-border exchanges over the past two years have taken place virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cheng said: "It was a great experience to work with and learn from researchers from different institutions. Some of them may have the chance to become our potential partners."

Qian, who is also a chair professor at the Department of Ocean Science at HKUST, said more cross-border collaboration would help Hong Kong marine scientists tap the nation's top scientific resources.

It costs hundreds of millions of yuan to build an oceanographic survey vessel, which no local institution can afford, Qian said, adding that mainland institutions also have advanced equipment that is not available in Hong Kong.

ALSO READ: HK resident gets top maritime accreditation

After returning to the city in mid-June, Cheng sent the samples she collected from the South China Sea to a laboratory in Beijing for genetic sequencing. Although she is still awaiting the results, she believes they could help her carry out further research.

As more scientists from Hong Kong become involved in national programs, the local marine research laboratory branch has enhanced cross-border collaboration by inviting more mainland and overseas scholars to join its work. The branch now has a total of 98 oceanographers from Hong Kong, the mainland and overseas countries as members.

The branch was established as Hong Kong's innovative and technological ambitions were backed by strong support at national level.

In June 2017, in a joint letter to President Xi Jinping, 24 Hong Kong academicians from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering said they wanted to contribute to the nation's scientific and technological development. Xi attached great importance to their wish, and issued instructions to promote scientific cooperation between the mainland and Hong Kong.

Initiatives launched

In 2018, in response to Xi's instructions, the central authorities announced a series of initiatives, which included allowing higher education and research institutions in Hong Kong to apply for national-level funding for science and technology, while receiving cross-border remittances for approved projects. The oceanographic community was among the first beneficiaries.

Since 2019, the Hong Kong branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou) has received 114 million yuan (US$16.23 million) in national funding, which is used mainly for research, expeditions, and international exchanges and cooperation.

Qian said the central government also allows faculty members at Hong Kong universities to apply for grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Ministry of Science and Technology. He said this policy has had a great impact, as it encourages more Hong Kong scholars to actively understand the nation's progress in science and technology, allowing them to align their personal development with that of the nation's.

In recent years, more Hong Kong education and research institutions have partnered with mainland counterparts in marine science.

In 2020, the University of Hong Kong and the Institute of Oceanology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences established the Joint Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environmental Sciences. HKUST launched joint doctorate programs in marine environmental science with the Guangzhou and Zhuhai branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory and the University of Shenzhen.

Last month, Cheng, from HKUST, received a text message from another young marine scientist who was setting off on a trip to the South China Sea with colleagues. It was the researcher's maiden voyage, and she wanted some advice from Cheng.

Sending her a long list of tips for the trip, Cheng remembered her first such voyage, which increased her enthusiasm for marine science.

She has that monthlong trip to the South China Sea in May to thank for her personal growth and for the city's gains in marine science.

Ivy Cheng Aifang (right) examines samples collected from the South China Sea. (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)

Ivy Cheng Aifang (right) examines samples collected from the South China Sea. (PHOTO / CHINA DAILY)