The wild boar population in Hong Kong is a complex issue, with human-boar conflict, and debate over humane methods like culling, contraception, and habitat enhancement to balance the needs of residents, animal rights groups, and indigenous species. Oasis Hu investigates in Hong Kong.

Having disrupted the natural habitat of wild boars, native to Hong Kong, can the unavoidable human-boar interface be managed? Wild boars have a prolific breeding rate depending on food availability. Females give birth up to twice a year, with litters of four to 12. They lead their litters into human living space for food. Some residents, feeling empathy, feed them. Others consider them a nuisance and complain about noise, disease risk, and even attacks.

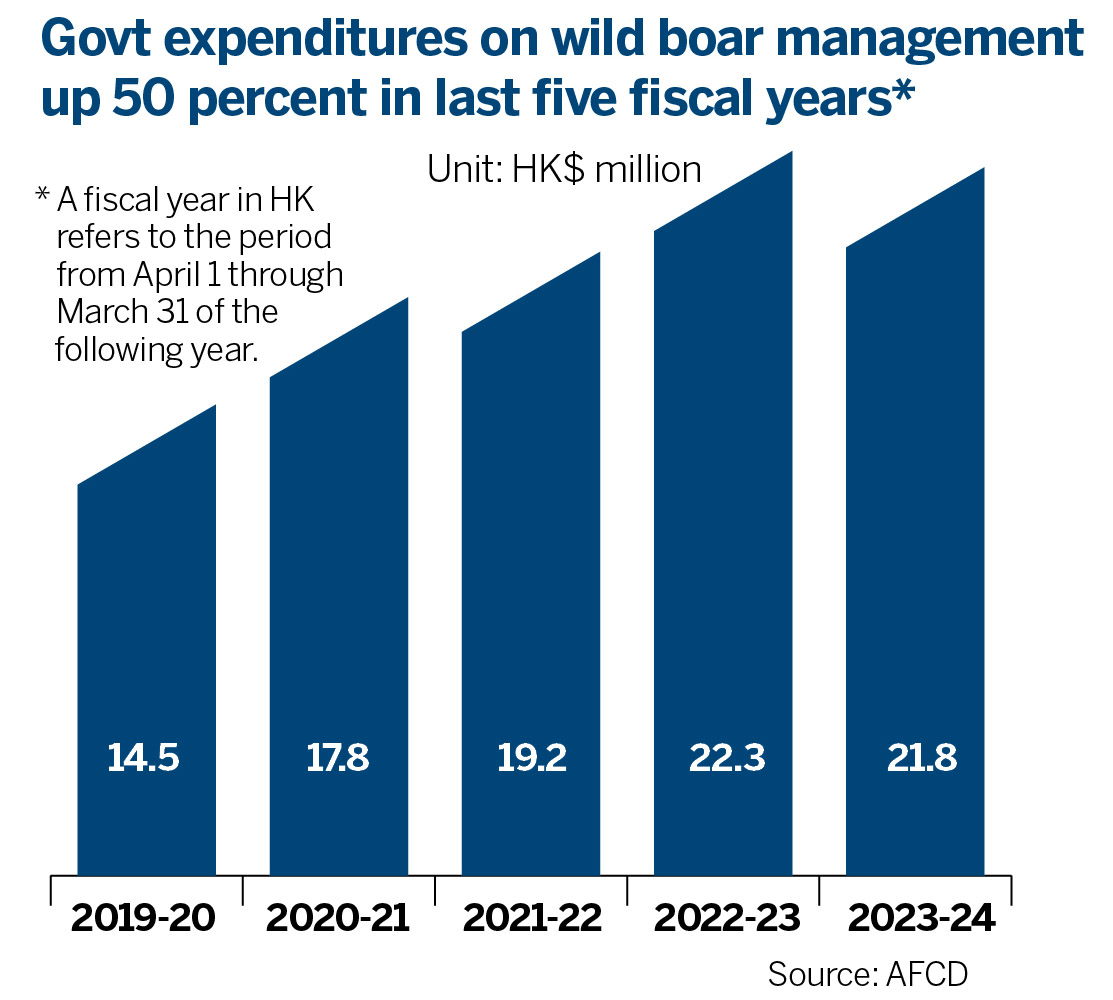

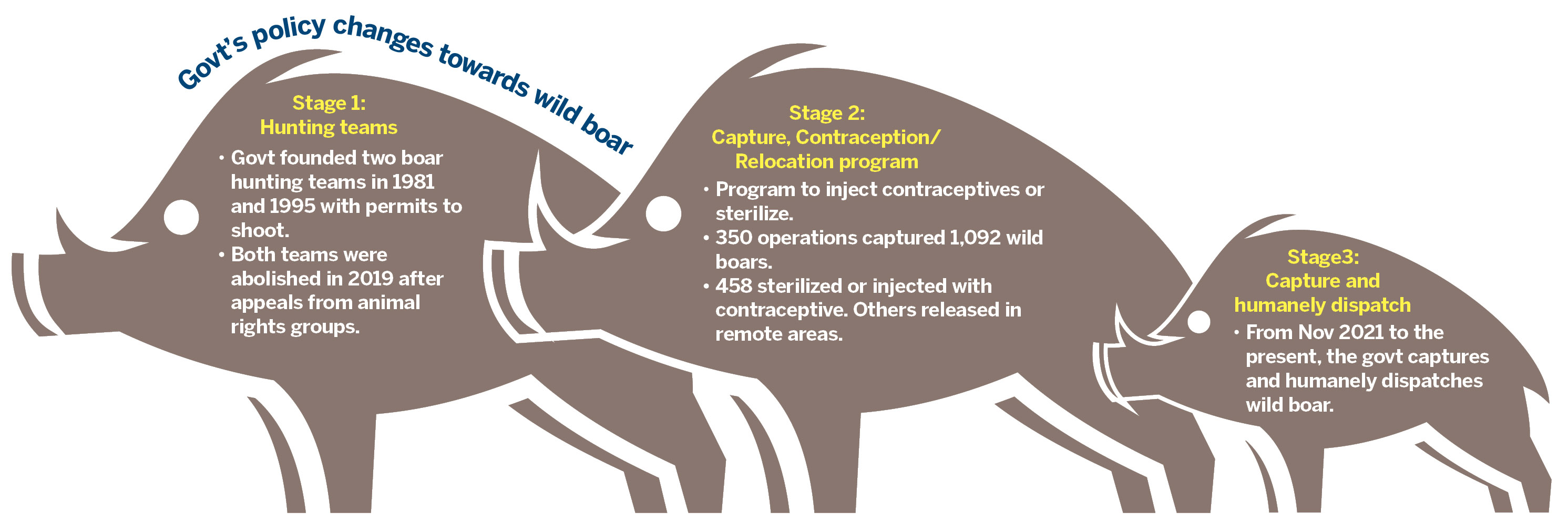

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government established two wild boar hunting teams in 1981 and 1995, permitted to carry firearms to shoot. Following outcries from animal rights groups, such hunting was stopped in 2019. Instead, from late 2017 to November 2021, the government opted to capture wild boar and inject contraceptive vaccines, or sterilize them.

The 350 operations in that period captured 1,092 wild boars, of which 458 were injected with contraceptives or sterilized. However, the prolific breeding rate of wild boars defeated that measured approach over time.

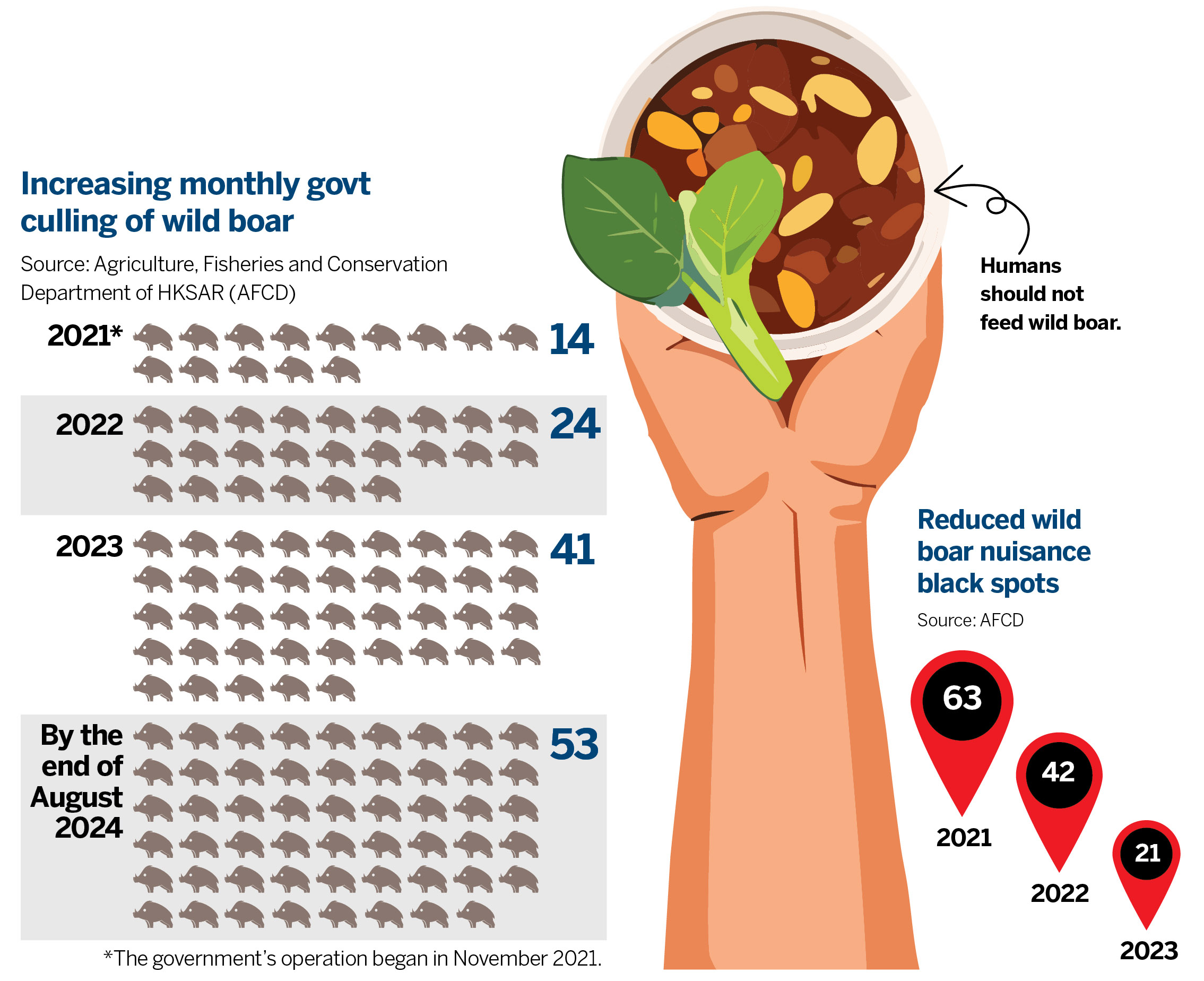

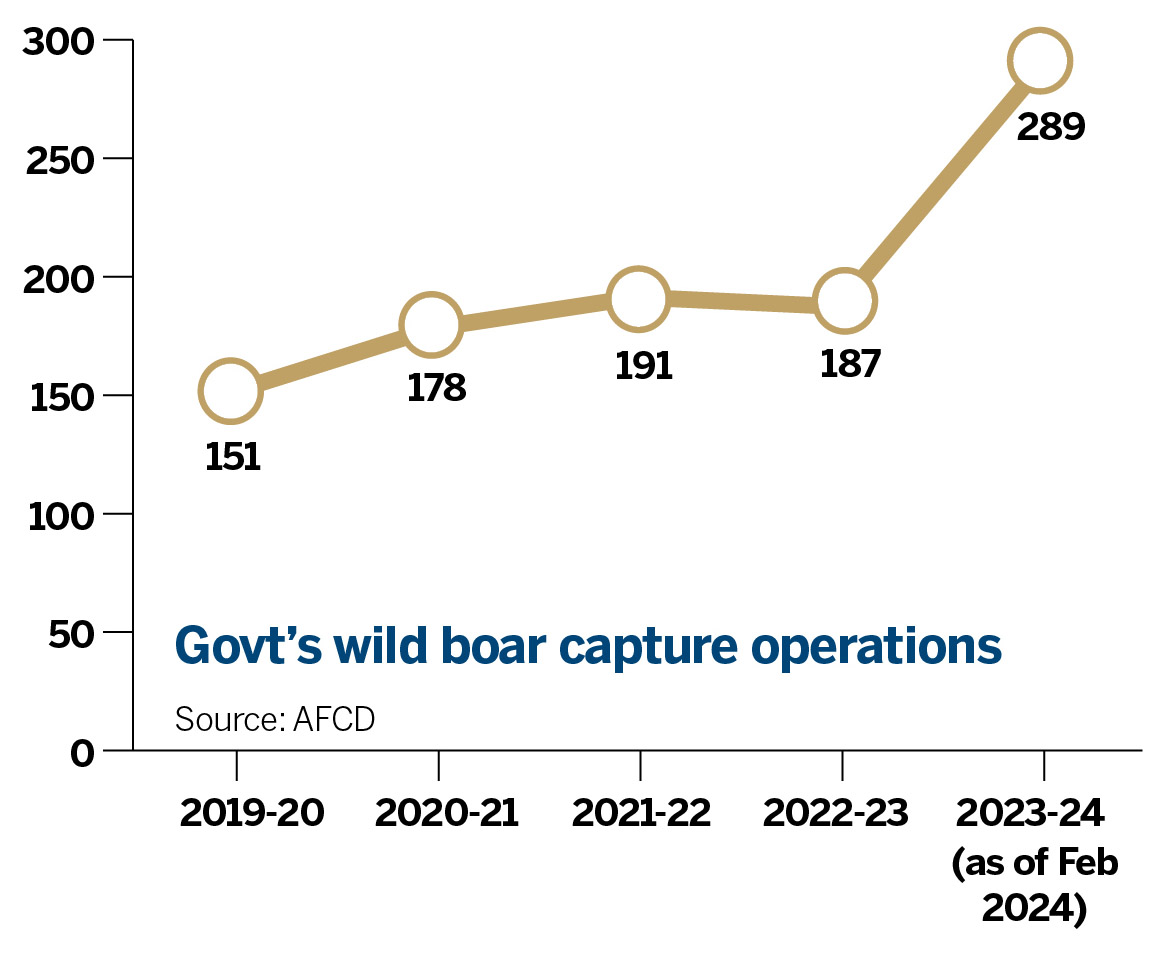

In November 2021, the government dispensed with the contraception and sterilization program. It opted to capture and kill for efficiency. It labels the killing “humane dispatch” to pacify rights groups. From November 2021 through August this year, a total of 1,231 wild boars had been dispatched. In the first eight months of this year alone, the government culled 422 wild boars, at an average of 53 per month. This is a 120 percent rise over the average monthly cull for 2022.

The Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department says that hot spots of wild boar trouble were halved from 42 in 2022 to 21 in 2023. Complaints in 2023 were 20 percent below 2021 with a 55 percent decline in reported cases.

Differing data

Official data differs on the total number of wild boars. Government statistics state there were 1,830 wild boars in 2022, while a Legislative Council research paper 2022 indicated 3,300 boars, 80 percent higher. A consistent data set of relevant parameters to map wild boar populations is missing.

Bond Shum Ting-wing, founder and conservation director of Outdoor Wildlife Learning Hong Kong, an environmental education unit established in 2016, regrets the lack of clarity in measuring, monitoring and controlling the wild boar situation.

Shum raises the question of how to assess the carrying capacity of wild boars by region, from the food supply available in their forest environment, plus other relevant data, to profile optimum target numbers to resources. These specifics are not available. A blanket culling, Shum says, is not a solution.

Japan has a similar problem of wild boars on the fringes of parks. They regularly monitor metrics such as sight rate, fecal distribution density, natural growth rate, capture rate, and number of hunters per area. Japan sets annual cull targets by specific geography.

Animal rights activists

Fiona Woodhouse, deputy director (welfare) of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, cautioned that relying solely on data points cannot truly validate the effectiveness of boar-control policies.

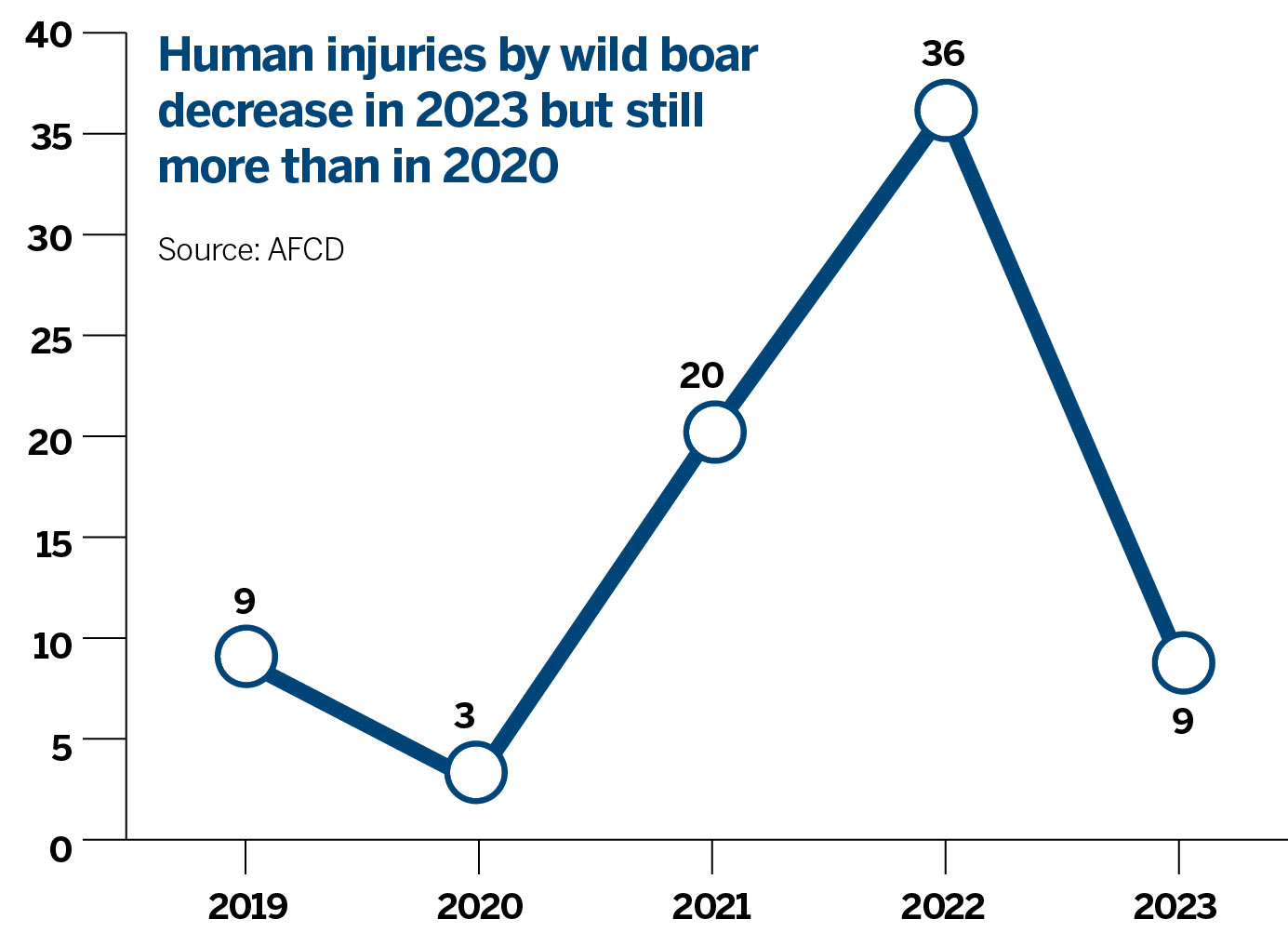

Wild boar disturbances stem from multiple factors, said Woodhouse. The high number in 2021 may have been caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, when people were mostly confined to their homes, resulting in a higher frequency of wild boar sightings.

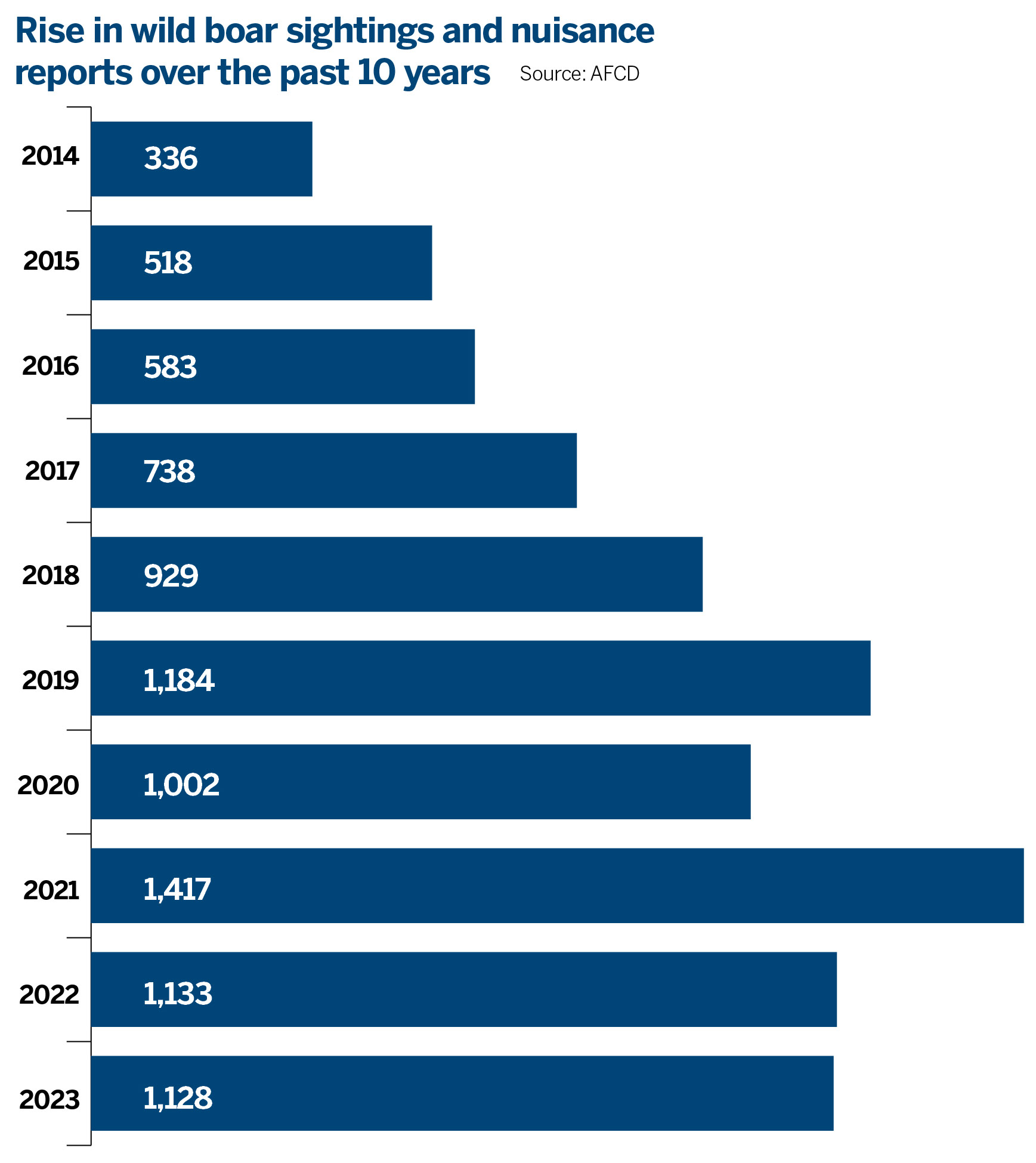

The Hong Kong Wild Boar Concern Group, which lobbies for wild boar protection, said the number of wild boar nuisance incidents remained steady at 1,000 to 1,200 before and after the culling. Two years after the culling, the number of reported injuries was 36 in 2022 and nine in 2023, exceeding the number of nine in 2019 and three in 2020, before culling measures.

The group feels the government’s hog-killing may have heightened resident hostility toward the wild boar. Shum disagrees with the assumption that the culling of wild boar aggravates conflict, without research verification.

Many people believe the increase in wild boar population is because of the absence of predators like tigers and pythons. Hong Kong has been without tigers and pythons for decades, noted Shum, yet the problem of wild boars only gained prominence in recent years. Extensive development of green reserves encroaches into the wild boars’ habitat, forcing them to forage for food in urban areas, said Shum.

Chan Suk-kuen, founder of the Society for Abandoned Animals ltd, observed that wild boars may enter urban spaces to seek food but if they fail to find any, they return to the forest. Wild boar mothers reportedly limit the number of offspring they have to match food resources in nature, to ensure survival.

Both Chan and Shum agree the root cause of wild boar nuisance arises from human behavior in feeding, and lax rubbish disposal. Feeding can disrupt the innate wild boars’ ability to regulate offspring numbers sustainably. It can also alter their behavior by reducing their fear of humans. Feeding wild boars is “cheap compassion”, said Chan, which ultimately brings culling on them.

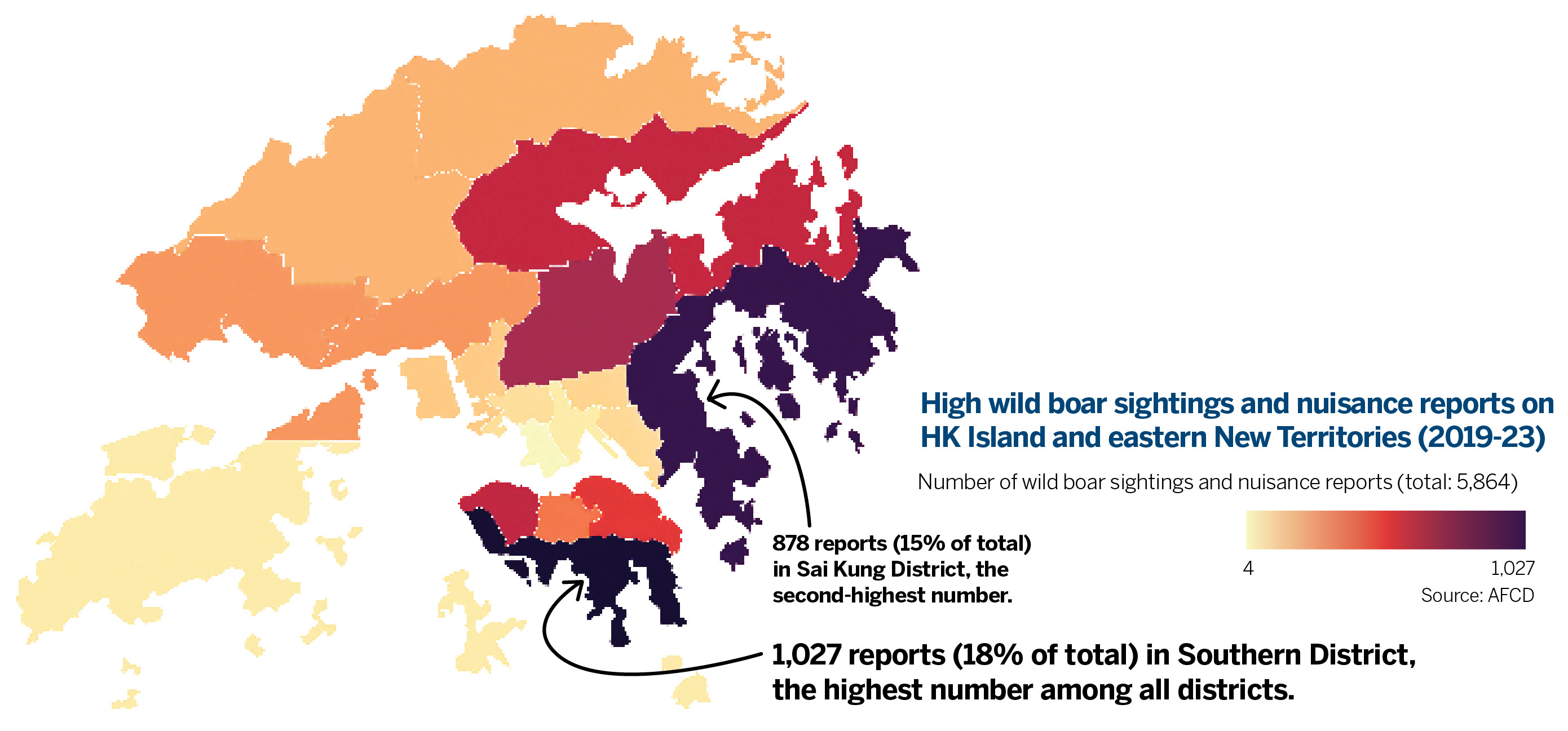

Woodhouse focuses on food being left behind at country parks after camping and barbecues, recklessly feeding wild boars. These occur across the territory wherever barbecue pits and camp sites are provided at park reserves and users fail to dispose of leftover food.

Containment measures

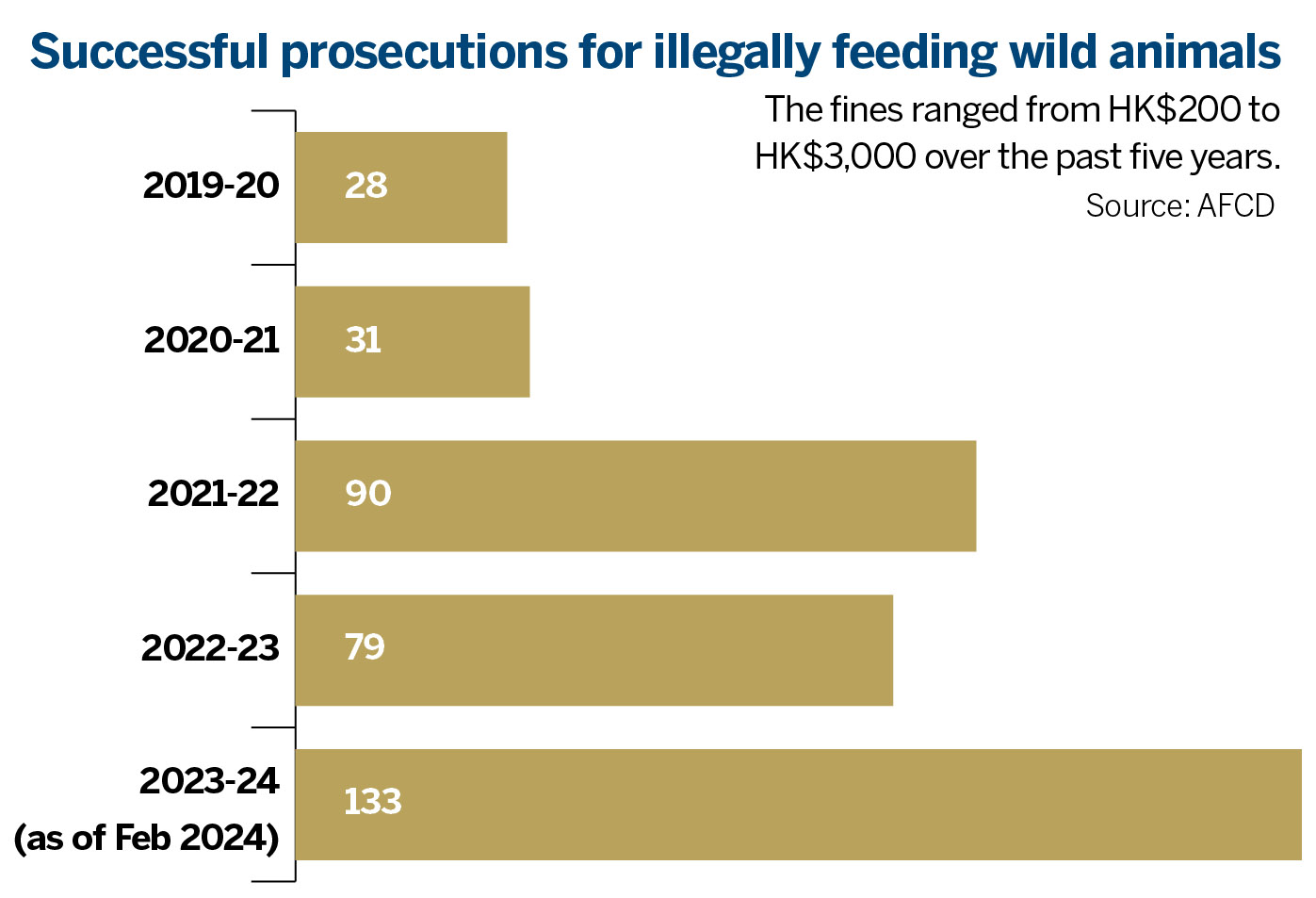

Feeding wild animals, including wild boars, is prohibited across Hong Kong. Offenders were previously liable to be prosecuted under the Wild Animals Protection Ordinance and subject to a maximum fine of HK$10,000 ($1,283).

The government submitted the revised Wild Animals Protection (Amendment) Bill 2023 to the Legislative Council in November 2023, increasing the maximum penalty for illegal feeding to a fine of HK$100,000 and a year’s imprisonment.

The Legislative Council passed the bill to take effect from Aug 1. It introduced a fixed penalty fine of HK$5,000 for illegal feeding, and expanded the categories of enforcement officers.

In the past two years, the government went after 30 people for illegally feeding wild animals. Only 17 were convicted, with fines ranging from HK$500 to HK$1,000. Shum feels stricter law enforcement is necessary to make existing laws effective.

Principles of coexistence

If a species is native and indigenous to the area, it has the right to be protected. It needs to be given the conditions to survive sustainably. Invasive species that are not native or indigenous, have to be actively removed from breeding, to preserve the food resources for native species. Wild boars are both native and indigenous, so they have the right to be where they are.

Shum and Woodhouse suggest that the government seek more holistic analyses of wild boars’ ecology to address concerns of residents and animal rights activists. To map wild boars’ habitat, food resources and density, the government can collaborate with NGOs and universities to research and compile data for a targeted plan, for effective containment of the population.

Both Shum and Woodhouse call for more green belts, wetlands, and ecological corridors to buffer humans’ and wild boars’ living environments. This can benefit not only wild boars but also preserve biodiversity in nature. Chan said the boundary between wild and domesticated animals is blurring with the tendency of humans to keep exotic animal species as pets. This shift flags the need for an animal welfare policy, said Chan.

Woodhouse notes there is an inherent imbalance in power between the dominant human species and animals. Humans exhibit “schizophrenia” toward animals, resulting in a sliding scale of tolerance, and inconsistent ethics in animal treatment. They can view one species differently from another, depending on context.

Rats can be pets, research experimentation subjects, or be consumed as food, observed Woodhouse. Society has not yet formed a consensus on how to treat all animals fairly. She calls for respect for all life forms, and ethical and humane treatment in methodologies and policies applied to animals.

What's next

- Use consistent data by region to set optimum wild boar numbers

- Enforce legal penalties for feeding wild animals

- Manage garbage more effectively

- Green reserve development should include wildlife impact studies

- Teach schoolchildren about wildlife responsibility

Contact the writer at oasishu@chinadailyhk.com