The surge in private EVs and planned conversion of public transport needs infrastructure for fast chargers, which may exceed the capacity of the electric power grid. Should the SAR government fund everything required to achieve net neutrality by 2050 including battery recycling and alternative hydrogen fuel energy? Reports Luo Weiteng.

Phasing out fossil fuel-powered private and public vehicles and moving toward electric energy sounds virtuous and progressive. But doing so requires a holistic appraisal of any consequences: recycling of toxic used batteries, fast charging points, and upgrading the power grid.

There is significant excess of air-conditioning usage in Hong Kong — estimated at 20-30 percent, compared to the Chinese mainland. That may provide sufficient scope to manage the short-term demands on the power grid.

Fast chargers need 30 minutes to attain an 80-percent charge. Slow or medium chargers take six to eight hours! Motorists do not have that kind of time to waste. Availability of fast charging points is a hurdle the city must overcome.

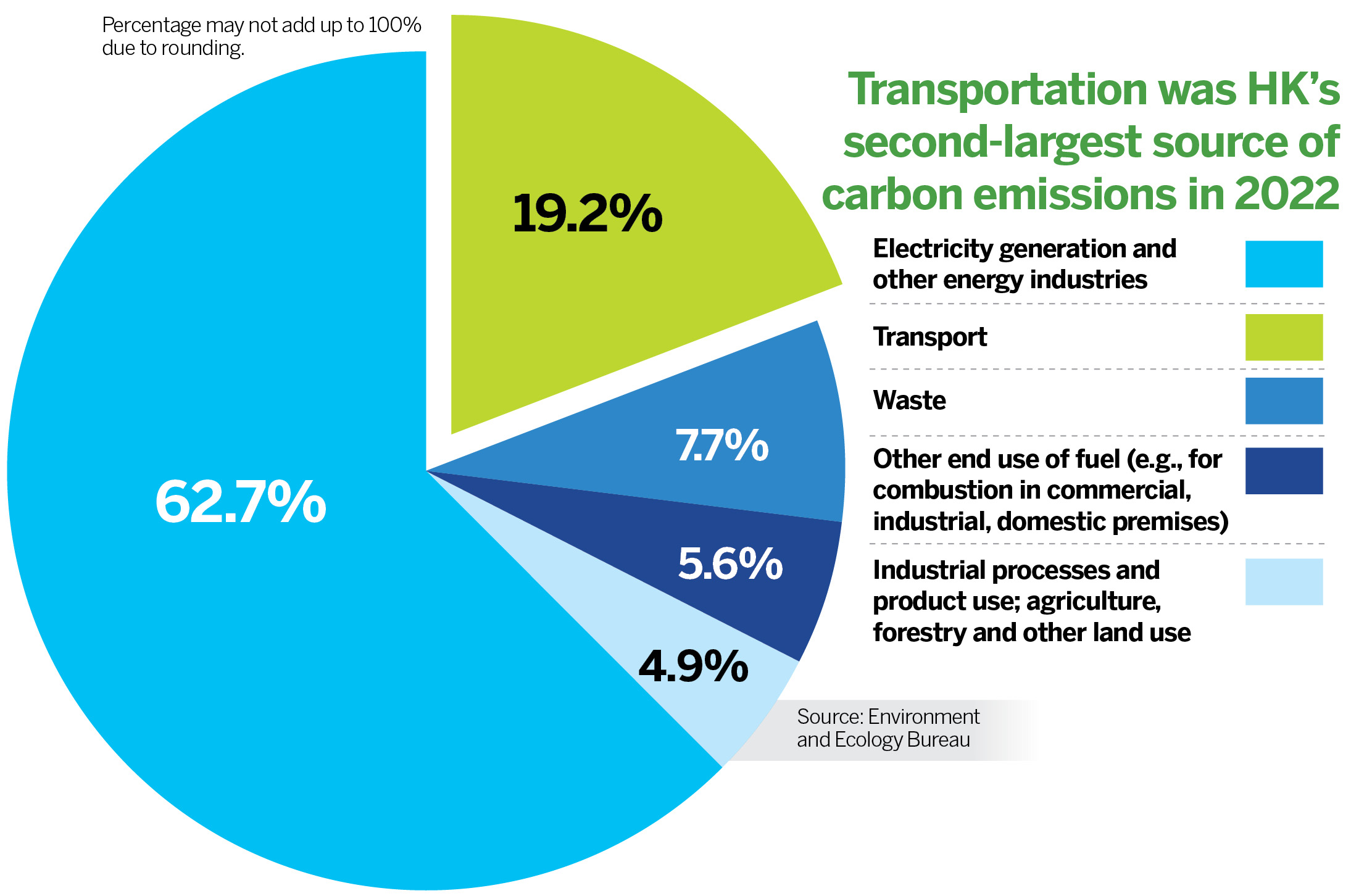

Transportation contributes 20 percent of all carbon emissions by sector, after power generation. The demand and supply matrix for the electric vehicles’ ecosystem needs to be mapped and integrated. The Hong Kong Roadmap on Popularisation of Electric Vehicles announced in March 2021, set 2035 as the target date to phase out petrol, diesel, petroleum gas and hybrid private cars.

EV surge

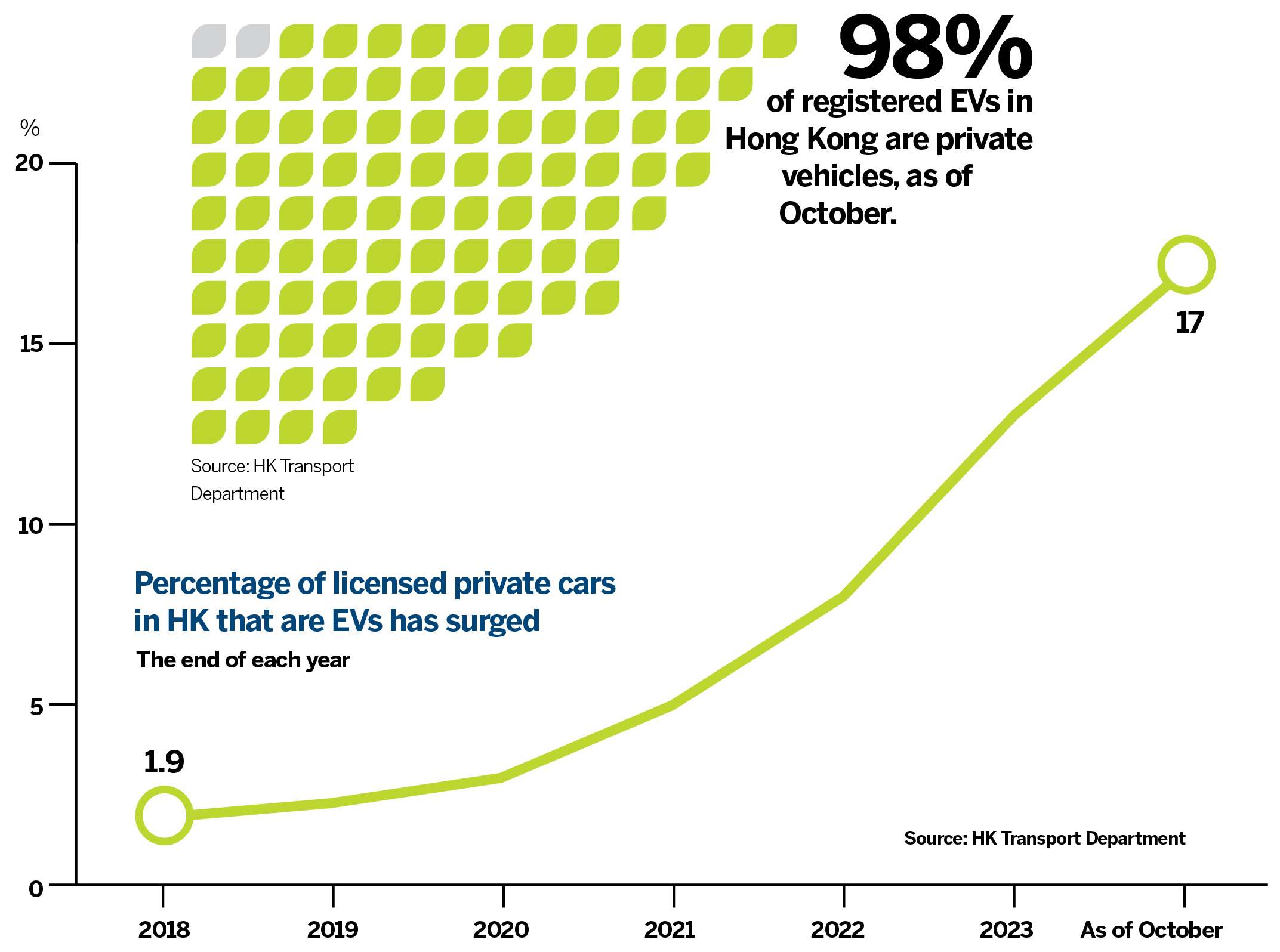

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’s One-for-One Replacement Scheme introduced in 2018 incentivized car owners to scrap existing fossil-fuel cars for new EVs. By 2022, EV sales of 19,975 units exceeded conventional car sales, capturing 53 percent of the market — the highest ratio in Asia, and third-highest globally after Norway and Iceland, real estate advisory group CBRE Hong Kong reported.

CBRE stated that the city’s dense and fragmented ownership of buildings compared to single-owner landed properties in other countries, makes installing private EV chargers a challenge. “Over 90 percent of Hong Kong’s private residential buildings are stratified, underlining the complexity in addressing vested interests and public resource distribution.”

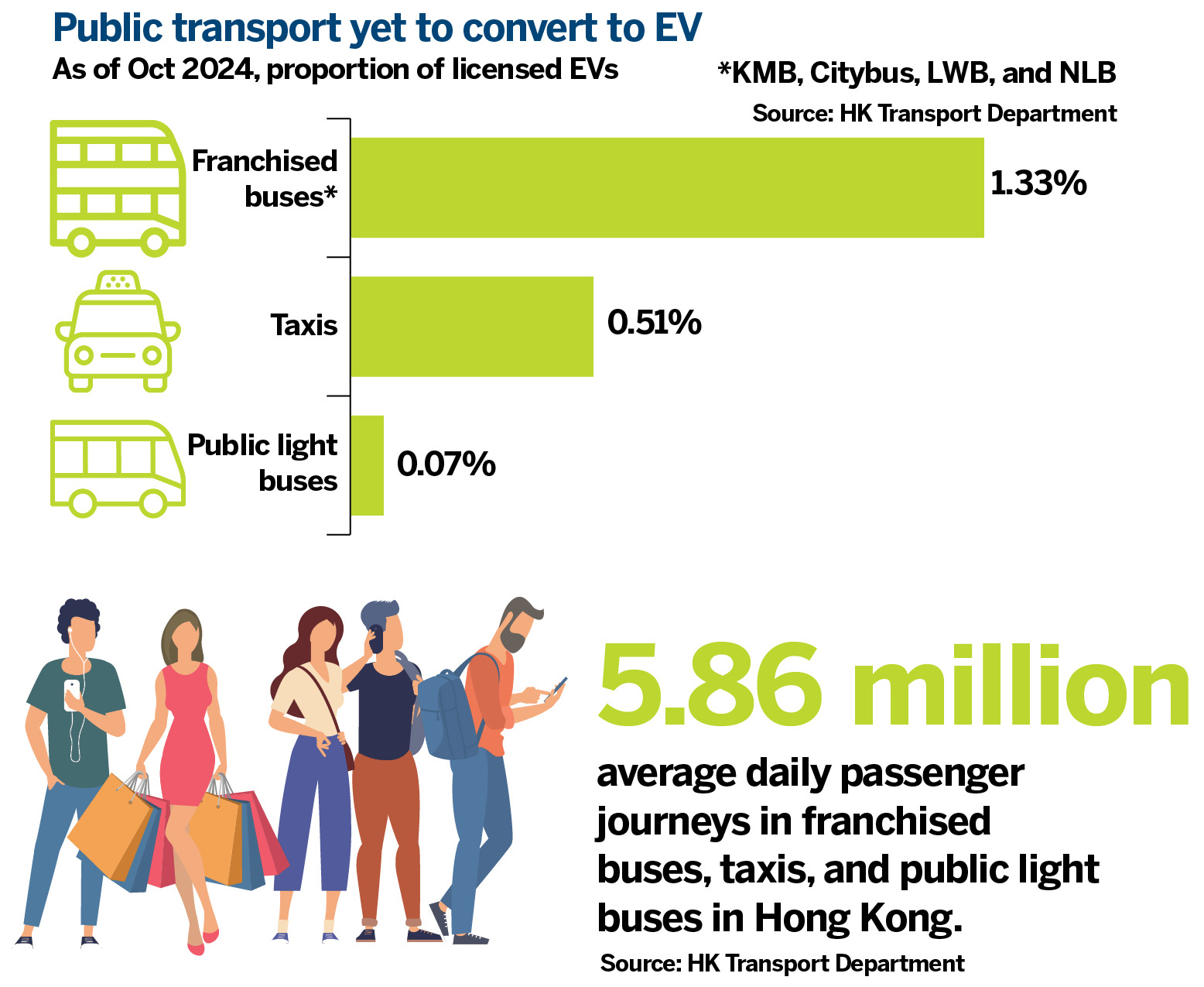

Currently, 98 percent of registered EVs in Hong Kong are private vehicles, said Gary Chan Hak-kan, legislative councillor and chairman of the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong. The city’s decarbonization strategies include net-zero electricity generation, energy saving, green buildings, and waste reduction.

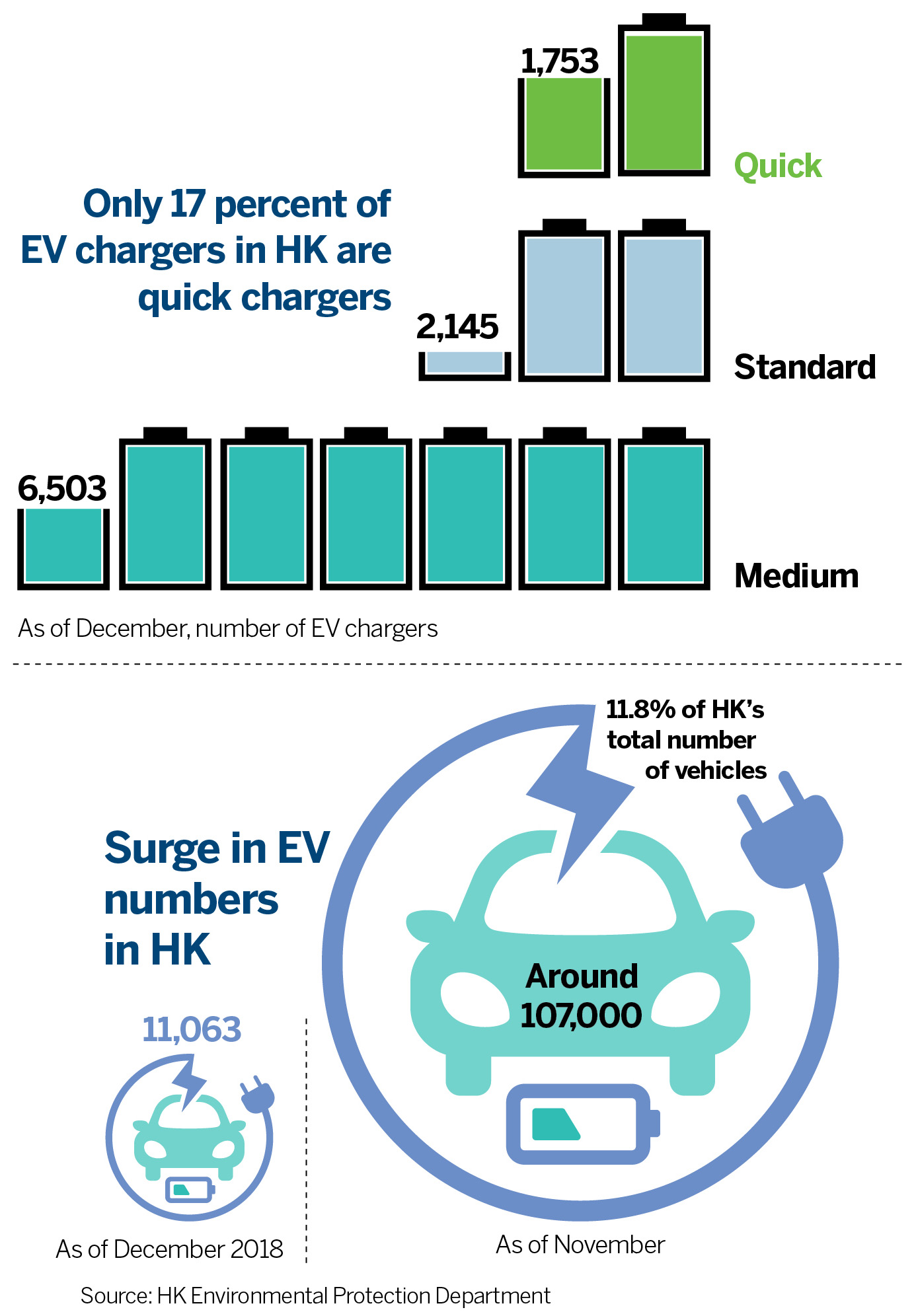

Data from the Environmental Protection and Transport Departments show new private EV registrations reached 68.3 percent of the market in October, up from 6.3 percent in 2019. EVs totalled 107,000 as of November, up from 11,063 in 2018, and represented 11.8 percent of the total number of vehicles.

The SAR government’s focus is shifting to public transport. The Green Transformation Roadmap of Public Buses and Taxis released in December, allocated HK$750 million ($96.4 million) in subsidies to taxis and franchised bus companies for purchasing EVs. Public transport contributes 1.4 million tons, or 4 percent of the city’s total carbon emissions.

Fast chargers

Gary Ng Cheuk-yan, senior economist of thematic research for Asia Pacific at Natixis Corporate and Investment Banking, notes that Hong Kong’s high population density makes EVs perfect for short-distance commutes, but it also makes building charging stations more challenging. “Providing affordable and efficient charging facilities is key to promoting EVs, especially with the limited parking space and the time needed to charge,” said Ng.

The Transport Department confirmed there were 10,401 EV chargers for public use in December, with 200,000 EV-charging parking spaces expected by mid-2027. Du Yonghai, chief innovation officer of the Hong Kong Productivity Council, contrasts Hong Kong’s 1:11 ratio of chargers to EVs with 1:3 on the Chinese mainland.

Furthermore, only 1,753 of 10,401 EV chargers are quick chargers. Chan called for upgrades to fast or ultra-fast chargers. The 2024 Policy Address set aside HK$300 million to install 500 quick-chargers by 2027, and 3,000 by 2030.

Power grid upgrade

Du flagged the extra load on the power grid, asking, “If more faster and ultra-fast chargers come into service, can the power grid handle the large, localized electric currents and voltage generated?” Du highlights the need for renovation, reconstruction, debugging and optimization to upgrade the power grid for fast-charging points.

Should the HKSAR government bear the full burden of ensuring clean energy? Du notes there is great demand for private equity and social capital funding, while the agreed global temperature rise of 1.5 C has already been breached — with forest fires, heatwaves, and more devastating global weather effects.

The power grid upgrade is complicated by the variety of standardizations in the EV design, requiring charging stations to adapt to all types of charging plugs. All this, even before EV maintenance can be factored for users. Du foresees a shortage of EV technicians. By November, the Transport Department had approved 386 EV models from 18 sources, of which 86 were for buses and commercial vehicles.

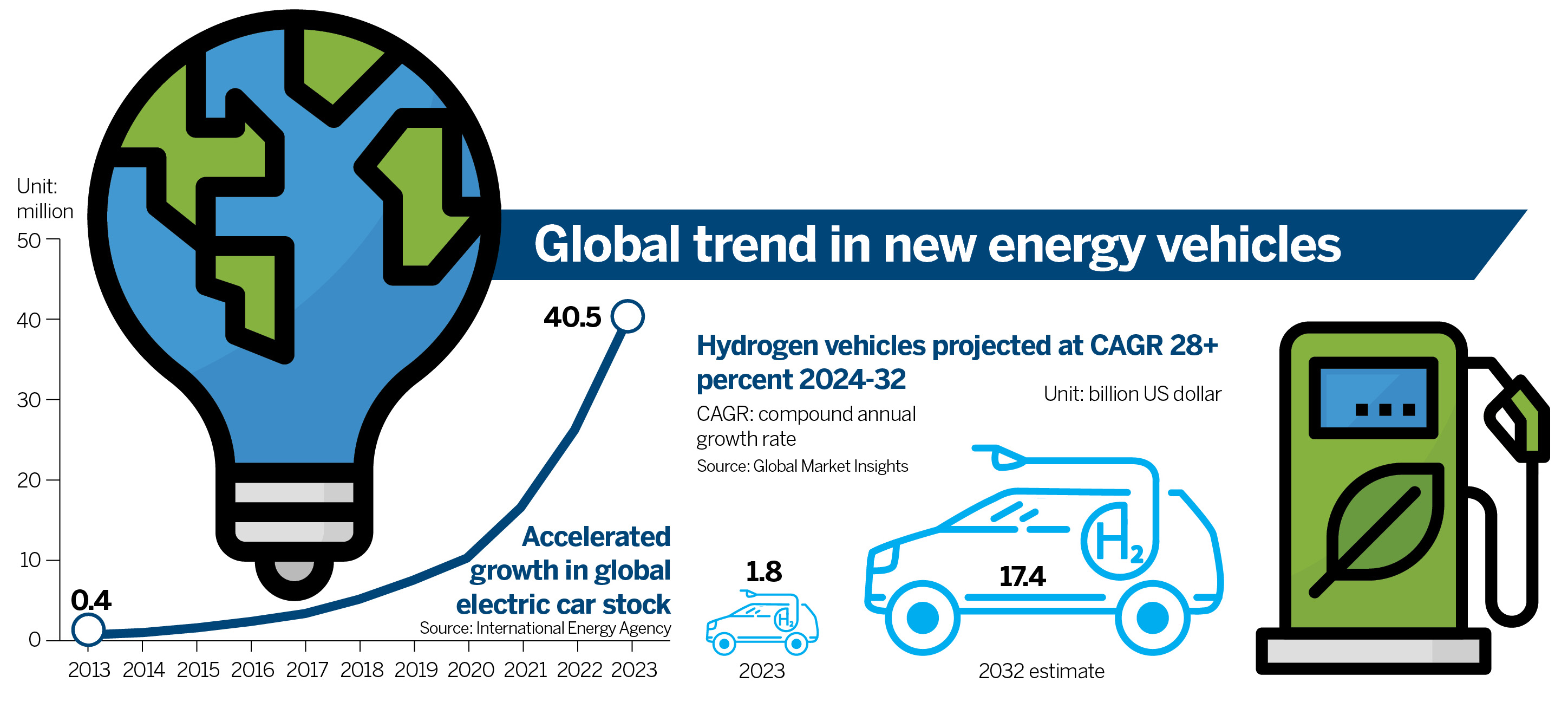

China Petroleum & Chemical Corp (Sinopec), the world’s largest refiner, launched the city’s first public hydrogen refueling station in December.

It marks a milestone in the search for clean energy alternatives. Du notes that hydrogen adoption requires the development of infrastructure, storage, distribution logistics, safety and security. Regulations and standards are yet to be formalized.

Battery hazard

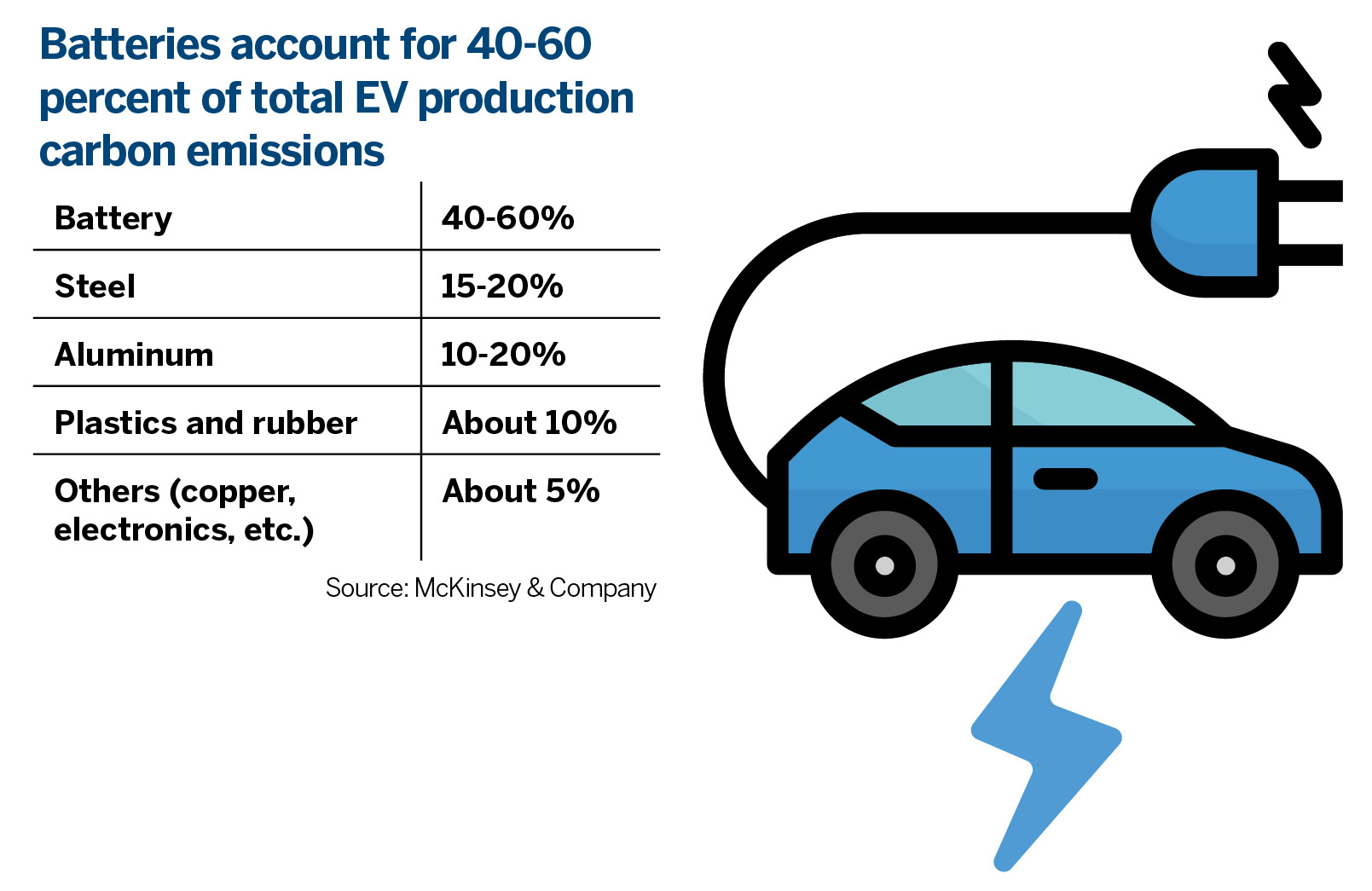

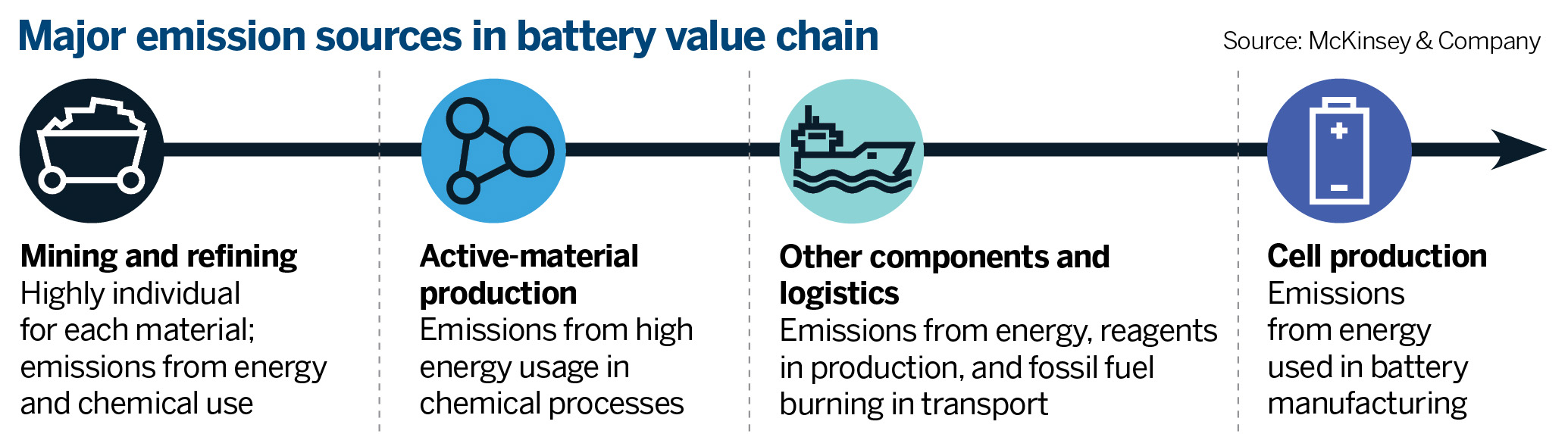

In 2023, consulting firm McKinsey estimated that production of the large lithium-ion batteries used to power EVs was the biggest source of embedded emissions for both electric cars and trucks, accounting for 40 to 60 percent of total production emissions. This back-end hazard of EVs is seldom mentioned in industry correspondence.

Dumping toxic used electric batteries in landfills is not an option. Recycling can theoretically recover valuable lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite and manganese from depleted batteries, to reuse for new.

These end-of-life recovery processes are still under development to ascertain their economic feasibility. It is hoped these issues will be resolved for EVs within the 10-year life cycle of the first wave of batteries.

Norway has the world’s highest electrified public transport — at almost 90 percent of all new cars sold, the Norwegian Road Federation reported. The Norwegian Parliament set 2025 as the date for it to achieve 100 percent battery-powered transport.

A comprehensive network of 9,000 fast chargers are available across its sparsely populated countryside. Norway allows a VAT exemption for vehicles costing up to 500,000 kroner ($44,250), while imposing higher taxes on non-battery powered vehicles from Jan 1.

The European Union, Japan, and the US state of California, have all vowed to stop selling new fossil-fuel vehicles by 2035. Mercedes-Benz and BMW plan to cease sales of fuel vehicles by 2030, Volkswagen by 2035 and Honda by 2040, said Chan Ching-chuen, director of the EV research center at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and founding president of the World Electric Vehicle Association.

Chan cites Shenzhen as a model where strong government regulatory and financial support have allowed it to run electric buses since 2010, and a fully electric bus fleet since 2017. In 2018, Shenzhen went all-electric on taxis too. EV maintenance and battery recycling developments are on track for sustainability.

What’s next

- Set timeline for buses and taxis to end the sale of fuel-engine vehicles.

- Leverage charging network and electrified ecosystem, for driver-assistance solutions.

- Accelerate EV battery recycling and self-drive systems.

- Use Chinese mainland’s stable hydrogen production for viable alternative clean energy.

- Align carbon-neutrality in shipping and aviation, for total transport sustainability.

Contact the writer at sophialuo@chinadailyhk.com